The Killing of a Sacred Deer

In the uncanny valley of a Yorgos Lanthimos film, characters resemble human beings … but not entirely. In movies such as Dogtooth and The Lobster, the Greek writer-director has become a maestro of the queasy/funny horror-comedy, turning our universal anxieties into psychologically rich satires in which life’s mundane surfaces give way to dark, often bloody realities we don’t want to acknowledge. His movies are funny because they’re so shocking and disturbing because they’re so true.

But for them to really soar, their provocations need to be grounded in recognizable behavior, which gives Lanthimos a foundation to then stretch his extreme stories past their breaking point. But with his latest, we see what happens when his underlying ideas are not as complex as the intricacies of his execution. The Killing of a Sacred Deer is endlessly watchable but only intermittently arresting—you’re held captive by its craftsmanship, even if you find yourself not particularly invested in how it all plays out. In his best films, Lanthimos tweaks real life in a way that encourages us to dissect his metaphors and see ourselves in his bizarre dramatic players. With Sacred Deer, we can sit back a little easier—his grip isn’t as sure, and therefore not as suffocating or brilliant.

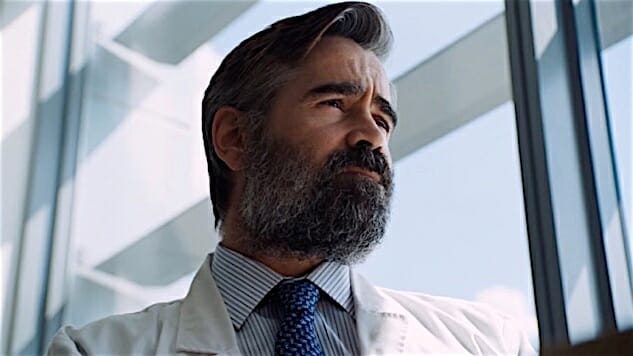

The film reunites Lanthimos with his Lobster star Colin Farrell, who plays Steven, a cardiologist, who’s married to an ophthalmologist, Anna (Nicole Kidman). They have two children, teen Kim (Raffey Cassidy) and her younger brother Bob (Sunny Suljic). It would be hard to describe their personalities because, in typical Lanthimos fashion, they don’t really have any. Speaking flat, unremarkable dialogue, the family members seem content as they discuss chores, their outfits, how their day was. But their posh house and well-manicured lawn belie an unspoken tension within the home—a creeping malaise that these attractive, accomplished people can’t quite articulate.

Quickly, Sacred Deer introduces us to the fly in this particular ointment. His name is Martin (Barry Keoghan), a moody teen who seems as lobotomized as the other characters. There’s one crucial difference, though: He has befriended Steven for reasons that feel sinister but will only eventually become clear, and he keeps insinuating himself into the man’s world, showing up at the doctor’s hospital or trying to corral him into having dinner at his and his mom’s place. Where Steven and his family have a blissed-out tranquility to their exchanges, Martin lets his simmering undercurrents wash across his face, hinting at something unwell—something not quite right—about this young man.

It wouldn’t be much fun to reveal where Sacred Deer goes from there, but suffice it to say that Steven’s almost clandestine friendship with Martin has to do with an unexpected shared past. And you can be sure that this friendship will shift radically once Martin decides that he wants more from Steven than he’s willing to offer this seeming stranger.

Dogtooth and The Lobster were excellent, in part, because Lanthimos and his frequent cowriter Efthymis Filippou constructed ingenious premises that, no matter how fanciful they were, reverberated with primal fears. (Dogtooth’s demented family echoed the worries of new parents trying to protect their children from the scary real world. The Lobster’s future society, which required individuals to mate or else, spoke to romantic conformity and the drudgery of matrimony.) Sacred Deer may be Lanthimos’ most visually and sonically ambitious work—technically, it’s pristine—but it doesn’t have the killer narrative hook that can tie all of the filmmaker’s disparate ideas together. His new movie is clever without ever quite deciding precisely what it’s about.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-