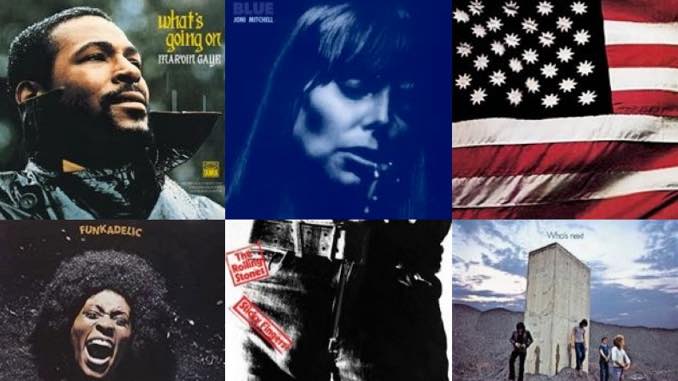

The 30 Best Albums of 1971

Fifty years ago was an extraordinary time for music. There were 12 albums from 1971 I consider masterpieces—among the finest releases from a dozen of the greatest music-makers in the modern era. These albums have stood up to the test of a half century of innovation. I still love new music, but I’d be hard-pressed to put on something from 2021 that I’ll enjoy as much as these works from Marvin Gaye, Joni Mitchell or Sly & The Family Stone.

Indeed, it was such a great year for music that I had too hard a time narrowing the list down to 25, so here are the 30 best albums of 1971, as voted on by the Paste music editors and writers.

30. Dolly Parton: A Coat of Many Colors In 1971, country fans had to stop thinking of Dolly Parton as Porter Wagoner’s gifted sidekick and acknowledge her as a giant talent in her own right. In April came the Joshua album with its #1 title track, and in October came the Coat of Many Colors album with two top-20 hits, including the title track, perhaps the best song Parton ever wrote. She wrote seven of the 10 songs, including such gems as the Carter Family-ish “My Blue Tears,” the heart-on-the-sleeve ballad “She Never Met a Man (She Didn’t Like)” and the wild story of a mother and daughter competing for the same “Travelin’ Man.” Check out those Bobby Dyson bass lines. —Geoffrey Himes

In 1971, country fans had to stop thinking of Dolly Parton as Porter Wagoner’s gifted sidekick and acknowledge her as a giant talent in her own right. In April came the Joshua album with its #1 title track, and in October came the Coat of Many Colors album with two top-20 hits, including the title track, perhaps the best song Parton ever wrote. She wrote seven of the 10 songs, including such gems as the Carter Family-ish “My Blue Tears,” the heart-on-the-sleeve ballad “She Never Met a Man (She Didn’t Like)” and the wild story of a mother and daughter competing for the same “Travelin’ Man.” Check out those Bobby Dyson bass lines. —Geoffrey Himes

29. The Doors: L.A. Woman There was always a dark undertow to the music of the Doors, a darkness that remained even as the band left behind the psychedelia of 1967 for the raw blues of the early 1970s on L.A. Woman. More than one woman has claimed to be the inspiration of its title track, but it could just as easily be about the city itself, that realm of glittering dreams and broken promises makes a “lucky little lady” and “another lost angel” flip sides of the same coin. Jim Morrison’s bawling vocal casts him a somewhat dispassionate observer (“Cops in cars, the topless bars/Never saw a woman so alone”) who nonetheless tumbles over into his own legend, as he slows down the pace to proclaim himself, “Mr. Mojo Risin.’” The propulsive music barely gives you a chance to catch your breath before cruising into oblivion. The album closes with the most atmospheric song by The Doors, “Riders on the Storm,” ushered in by the sound of an approaching thunderstorm and Ray Manzarek’s gently cascading keyboard line. Morrison coolly croons his way through a lyric that touches on isolation and impeding death (the hitchhiking killer in the second verse), with low key backing from the band that creates a haunting world of loss and desolation. —Gillian G. Gaar

There was always a dark undertow to the music of the Doors, a darkness that remained even as the band left behind the psychedelia of 1967 for the raw blues of the early 1970s on L.A. Woman. More than one woman has claimed to be the inspiration of its title track, but it could just as easily be about the city itself, that realm of glittering dreams and broken promises makes a “lucky little lady” and “another lost angel” flip sides of the same coin. Jim Morrison’s bawling vocal casts him a somewhat dispassionate observer (“Cops in cars, the topless bars/Never saw a woman so alone”) who nonetheless tumbles over into his own legend, as he slows down the pace to proclaim himself, “Mr. Mojo Risin.’” The propulsive music barely gives you a chance to catch your breath before cruising into oblivion. The album closes with the most atmospheric song by The Doors, “Riders on the Storm,” ushered in by the sound of an approaching thunderstorm and Ray Manzarek’s gently cascading keyboard line. Morrison coolly croons his way through a lyric that touches on isolation and impeding death (the hitchhiking killer in the second verse), with low key backing from the band that creates a haunting world of loss and desolation. —Gillian G. Gaar

28. Elton John: Madman Across the Water A year after Madman Across The Water was released, Elton John made Honky Château, which is considered one of his greatest works, has a stronger foothold in the canon, was better loved by critics and is ultimately probably the better album. “Honky Cat,” “I Think I’m Going To Kill Myself” and “Rocket Man” are classics, indeed, but there’s something special about Madman. It’s a wonderful display of the partnership between Elton John and songwriter Bernie Taupin—Taupin’s ability to tell a compelling story and John using his keys, his voice and his presence to make you care about the characters. There’s the weirdness and sadness of “Levon”—a song full of quirky names and scenarios but a feeling of longing and familial dysfunction all too common, backed with that punch of a chorus. There’s “Tiny Dancer,” which was and will always be great regardless of what sentimental movie scenes soundtrack it, and the powerhouse title track, of course. And even the deep cuts have their moments, most notably the mournful, mandolin-tinged “Holiday Inn.” —Lindsay Eanet

A year after Madman Across The Water was released, Elton John made Honky Château, which is considered one of his greatest works, has a stronger foothold in the canon, was better loved by critics and is ultimately probably the better album. “Honky Cat,” “I Think I’m Going To Kill Myself” and “Rocket Man” are classics, indeed, but there’s something special about Madman. It’s a wonderful display of the partnership between Elton John and songwriter Bernie Taupin—Taupin’s ability to tell a compelling story and John using his keys, his voice and his presence to make you care about the characters. There’s the weirdness and sadness of “Levon”—a song full of quirky names and scenarios but a feeling of longing and familial dysfunction all too common, backed with that punch of a chorus. There’s “Tiny Dancer,” which was and will always be great regardless of what sentimental movie scenes soundtrack it, and the powerhouse title track, of course. And even the deep cuts have their moments, most notably the mournful, mandolin-tinged “Holiday Inn.” —Lindsay Eanet

27. Serge Gainsbourg: Histoire de Melody Nelson It takes less than half an hour for the French maestro to take us through a semi-autobiographical concise exploration of seduction. Serge Gainsbourg was always known for his varied musical styling from album to album, or sometimes even song to song. However, Histoire de Melody Nelson’s consistency gives the album the sense that it is one long musical piece with different scenes. The term “concept album” is thrown about quite often, but Gainsbourg was more interested in telling a story than creating a perception. The musician’s funky bass lines, orchestral strings and a slam-poetry vocal delivery helps paint the harrowing story of Gainsbourg crashing his Rolls Royce into a teenaged beauty on her bicycle and the ensuing affair, creating a sense that the entire ensemble of songs is taken from a modern performance meant to be performed in opera houses instead of a studio. Only Serge Gainsbourg and his real-life muse Jane Birkin could have allowed the world into such intimate emotions. —Adam Vitcavage

It takes less than half an hour for the French maestro to take us through a semi-autobiographical concise exploration of seduction. Serge Gainsbourg was always known for his varied musical styling from album to album, or sometimes even song to song. However, Histoire de Melody Nelson’s consistency gives the album the sense that it is one long musical piece with different scenes. The term “concept album” is thrown about quite often, but Gainsbourg was more interested in telling a story than creating a perception. The musician’s funky bass lines, orchestral strings and a slam-poetry vocal delivery helps paint the harrowing story of Gainsbourg crashing his Rolls Royce into a teenaged beauty on her bicycle and the ensuing affair, creating a sense that the entire ensemble of songs is taken from a modern performance meant to be performed in opera houses instead of a studio. Only Serge Gainsbourg and his real-life muse Jane Birkin could have allowed the world into such intimate emotions. —Adam Vitcavage

26. Stevie Wonder: Where I’m Coming From This marks the beginning of Wonder’s transition from a cog in Motown’s hitmaking machine to a self-assertive, independent artist. He produced the whole thing himself and co-wrote all nine songs with his then-wife Syretta Wright. You can hear Wonder experimenting with the synthesizers, protest lyrics and funk rhythms that would define his masterpieces coming in a few years. Not all of it works, but his gift for melody is unfailing—“Never Dreamed You’d Leave in Summer” and the top-10 single “If You Really Love Me” are irresistible. —Geoffrey Himes

This marks the beginning of Wonder’s transition from a cog in Motown’s hitmaking machine to a self-assertive, independent artist. He produced the whole thing himself and co-wrote all nine songs with his then-wife Syretta Wright. You can hear Wonder experimenting with the synthesizers, protest lyrics and funk rhythms that would define his masterpieces coming in a few years. Not all of it works, but his gift for melody is unfailing—“Never Dreamed You’d Leave in Summer” and the top-10 single “If You Really Love Me” are irresistible. —Geoffrey Himes

25. Yes: Fragile It’s funny that fans and detractors of progressive rock both tend to view the genre as separate from the mainstream. The fact is, there are numerous examples where complexity and instrumental chops have aligned with commercial appeal. And when we imagine the apotheosis of music that can be challenging and accessible in equal measure, the conversation has to include Fragile, the fourth album by English prog rock giants Yes. The first offering by the classic-era lineup of Jon Anderson, Chris Squire, Steve Howe, Bill Bruford and Rick Wakeman, Fragile captures all the elements coming together for the band in a way that would cement the foundation for countless others to follow. All five musicians sound simultaneously muscular and limber as they weave ’60s pop stylings, driving rock, traditional English folk, classical and even a touch of Broadway into a vibrant blend, each player appearing to revel in showing off. Squire, for one, singlehandedly re-defines the role of the bass in a pop context, pushing the envelope on par with the likes of Paul McCartney, Larry Graham, Jr. and Jaco Pastorius. That said, no one in the band loses sight of core songwriting principles—in fact, Fragile showcases such seamless execution that it’s easy to forget just how groundbreaking Yes’s sound was in 1971. Anderson’s vocal melodies scrape the upper reaches of the stratosphere, while the band as a whole aims to push rock music to sublime new heights with breathtaking crescendos like “Heart of the Sunrise.” Listening back today, it’s no wonder that Fragile claimed a permanent place for progressive rock in popular music. —Saby Reyes-Kulkarni

It’s funny that fans and detractors of progressive rock both tend to view the genre as separate from the mainstream. The fact is, there are numerous examples where complexity and instrumental chops have aligned with commercial appeal. And when we imagine the apotheosis of music that can be challenging and accessible in equal measure, the conversation has to include Fragile, the fourth album by English prog rock giants Yes. The first offering by the classic-era lineup of Jon Anderson, Chris Squire, Steve Howe, Bill Bruford and Rick Wakeman, Fragile captures all the elements coming together for the band in a way that would cement the foundation for countless others to follow. All five musicians sound simultaneously muscular and limber as they weave ’60s pop stylings, driving rock, traditional English folk, classical and even a touch of Broadway into a vibrant blend, each player appearing to revel in showing off. Squire, for one, singlehandedly re-defines the role of the bass in a pop context, pushing the envelope on par with the likes of Paul McCartney, Larry Graham, Jr. and Jaco Pastorius. That said, no one in the band loses sight of core songwriting principles—in fact, Fragile showcases such seamless execution that it’s easy to forget just how groundbreaking Yes’s sound was in 1971. Anderson’s vocal melodies scrape the upper reaches of the stratosphere, while the band as a whole aims to push rock music to sublime new heights with breathtaking crescendos like “Heart of the Sunrise.” Listening back today, it’s no wonder that Fragile claimed a permanent place for progressive rock in popular music. —Saby Reyes-Kulkarni

24. The Beach Boys: Surf’s Up In 1971, The Beach Boys’ released Surf’s Up, and despite the tongue-in-cheek title (spoiler: The Beach Boys enjoyed surfing about as much as Brian looks like he does in the “Brian’s back!”-themed SNL sketch where Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi physically force him into the ocean), it was the darkest album the band would ever record. The album cover depicts a nod to “End of the Trail,” a sculpture featuring a broken-down Native American man who, after coming to a sudden halt, is about to plummet over an unseen precipice—given Brian’s all-consuming nervous breakdown within the next two years, the imagery is all too portentous. Straight from the discordant chords that open the album on “Don’t Go Near the Water,” the album is miles from “Surfin’ Safari” as an early pioneer of prog rock. Carl’s alien and ethereal “Feel Flows” finally connected The Beach Boys to the counterculture more than the album’s Kent State shooting protest jam “Student Demonstration Time” ever could, and the organ-laden “A Day in the Life of a Tree” and the haunting “Til I Die” may just be Brian’s last great compositions. But the real standout is the album’s title track, a leftover from Smile. “Surf’s Up” is innovative, enigmatic and sublime evidence of the woulda/coulda/shoulda run for their money The Beach Boys almost gave the Beatles in 1967. —Katie Cameron

In 1971, The Beach Boys’ released Surf’s Up, and despite the tongue-in-cheek title (spoiler: The Beach Boys enjoyed surfing about as much as Brian looks like he does in the “Brian’s back!”-themed SNL sketch where Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi physically force him into the ocean), it was the darkest album the band would ever record. The album cover depicts a nod to “End of the Trail,” a sculpture featuring a broken-down Native American man who, after coming to a sudden halt, is about to plummet over an unseen precipice—given Brian’s all-consuming nervous breakdown within the next two years, the imagery is all too portentous. Straight from the discordant chords that open the album on “Don’t Go Near the Water,” the album is miles from “Surfin’ Safari” as an early pioneer of prog rock. Carl’s alien and ethereal “Feel Flows” finally connected The Beach Boys to the counterculture more than the album’s Kent State shooting protest jam “Student Demonstration Time” ever could, and the organ-laden “A Day in the Life of a Tree” and the haunting “Til I Die” may just be Brian’s last great compositions. But the real standout is the album’s title track, a leftover from Smile. “Surf’s Up” is innovative, enigmatic and sublime evidence of the woulda/coulda/shoulda run for their money The Beach Boys almost gave the Beatles in 1967. —Katie Cameron

23. John Lennon: Imagine Perhaps atoning for sins committed in his heavy-handed salvation work on The Beatles’ Let It Be recordings, here co-producer Phil Spector brings a simplicity of instrumentation to Lennon’s brilliantly written tunes. Even today, the album retains its freshness (except maybe for that annoying sax solo on “It’s So Hard”—I don’t care if it is King Curtis). Compared to the soaring production of Simon and Garfunkel’s inspirational Bridge Over Troubled Water a year earlier, the title track relies on the profundity of Lennon’s words with a fitting, uncomplicated arrangement of piano, bass and drums and just a dusting of strings. And then there’s Lennon’s formidable vocals. While he moves us with his sincerity on “Imagine” he tongue-lashes his way through “Gimme Some Truth,” immediately starting with an obvious impatience and disgust at the incompetence of our political leaders. Later, in the same manner, he unabashedly burns his ex-songwriting partner Paul McCartney in “How Do You Sleep?” With every song a gem, this is John Lennon at his multi-layered best. —Tim Basham

Perhaps atoning for sins committed in his heavy-handed salvation work on The Beatles’ Let It Be recordings, here co-producer Phil Spector brings a simplicity of instrumentation to Lennon’s brilliantly written tunes. Even today, the album retains its freshness (except maybe for that annoying sax solo on “It’s So Hard”—I don’t care if it is King Curtis). Compared to the soaring production of Simon and Garfunkel’s inspirational Bridge Over Troubled Water a year earlier, the title track relies on the profundity of Lennon’s words with a fitting, uncomplicated arrangement of piano, bass and drums and just a dusting of strings. And then there’s Lennon’s formidable vocals. While he moves us with his sincerity on “Imagine” he tongue-lashes his way through “Gimme Some Truth,” immediately starting with an obvious impatience and disgust at the incompetence of our political leaders. Later, in the same manner, he unabashedly burns his ex-songwriting partner Paul McCartney in “How Do You Sleep?” With every song a gem, this is John Lennon at his multi-layered best. —Tim Basham

22. Genesis: Nursery Cryme Genesis flirted with—and arguably reached—greatness on their underrated second LP, Trespass, driven by a charismatic frontman (Peter Gabriel) and a folky 12-string elegance. They just needed some home-run hitters for that next leap into full-blown prog. Enter drummer Phil Collins and guitarist Steve Hackett, who solidified the classic quintet lineup with their blend of flash and sensitivity. Nursery Cryme is woefully under-produced compared to their subsequent ’70s classics, but the compositions unlocked new realms of imagination—from the gothic Victorian madness of opening epic “The Musical Box” to the symphonic splendor of closer “The Fountain of Salmacis.” —Ryan Reed

Genesis flirted with—and arguably reached—greatness on their underrated second LP, Trespass, driven by a charismatic frontman (Peter Gabriel) and a folky 12-string elegance. They just needed some home-run hitters for that next leap into full-blown prog. Enter drummer Phil Collins and guitarist Steve Hackett, who solidified the classic quintet lineup with their blend of flash and sensitivity. Nursery Cryme is woefully under-produced compared to their subsequent ’70s classics, but the compositions unlocked new realms of imagination—from the gothic Victorian madness of opening epic “The Musical Box” to the symphonic splendor of closer “The Fountain of Salmacis.” —Ryan Reed

21. Bob Marley & The Wailers: Soul Revolution Before the Wailers signed with England’s Island Records, the label that turned Bob Marley into an international superstar, the trio of Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston recorded for some 20 different small Jamaican labels. The best of those homegrown tracks were cut with the Barrett Brothers rhythm section for the innovative producer Lee “Scratch” Perry who created spare sonic settings worthy of the young men’s remarkable songwriting and singing. Perry elevated the group above the singles-only treadmill by creating actual albums: 1970’s Soul Rebels and 1971’s Soul Revolution. The latter contained early versions of such Marley standards as “Kaya,” “African Herbsman” and “Duppy Conqueror” and was released with a companion disc of dub versions. —Geoffrey Himes

Before the Wailers signed with England’s Island Records, the label that turned Bob Marley into an international superstar, the trio of Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston recorded for some 20 different small Jamaican labels. The best of those homegrown tracks were cut with the Barrett Brothers rhythm section for the innovative producer Lee “Scratch” Perry who created spare sonic settings worthy of the young men’s remarkable songwriting and singing. Perry elevated the group above the singles-only treadmill by creating actual albums: 1970’s Soul Rebels and 1971’s Soul Revolution. The latter contained early versions of such Marley standards as “Kaya,” “African Herbsman” and “Duppy Conqueror” and was released with a companion disc of dub versions. —Geoffrey Himes

20. Al Green: Al Green Gets Next to You With all due respect to his first two albums, this is the moment that Al Green found his footing as a performer and songwriter. Just compare the picture of Green on the cover of this album to the previous LP, 1969’s Green Is Blues. On the latter, he’s serious and brooding, tensed up to brace against some unknown spiritual or emotional attack. Just two years later, he looks like he has been set free and ready to face the future with a goofy grin and a swing in his step. Assisted every step of the way by his frequent collaborator Willie Mitchell, Green finds the smolder in The Doors’ “Light My Fire,” the raw need in “I Can’t Get Next To You” and the joyful submission in “God Is Standing By.” He also found the first flowers of his songwriting voice, contributing the timeless plea “Tired of Being Alone” and the acid funk romance of “You Say It,” among others, to this glorious and spiritual liberated masterpiece. — Robert Ham

With all due respect to his first two albums, this is the moment that Al Green found his footing as a performer and songwriter. Just compare the picture of Green on the cover of this album to the previous LP, 1969’s Green Is Blues. On the latter, he’s serious and brooding, tensed up to brace against some unknown spiritual or emotional attack. Just two years later, he looks like he has been set free and ready to face the future with a goofy grin and a swing in his step. Assisted every step of the way by his frequent collaborator Willie Mitchell, Green finds the smolder in The Doors’ “Light My Fire,” the raw need in “I Can’t Get Next To You” and the joyful submission in “God Is Standing By.” He also found the first flowers of his songwriting voice, contributing the timeless plea “Tired of Being Alone” and the acid funk romance of “You Say It,” among others, to this glorious and spiritual liberated masterpiece. — Robert Ham

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Paul McCartney could have formed the ultimate supergroup following the Beatles’ split, but he consciously aimed to sidestep such a high-profile venture. “I was looking for a new band rather than the Blind Faith thing, so I didn’t really want heavyweights,” he told Billboard in 2001, recalling his philosophy in the Ram era. That album, arriving one year after his homespun solo debut (and just ahead of his venture with Wings), was his first with a band mentality: Then-wife Linda McCartney adds charmingly rough-hewn harmonies throughout—and even co-writes some of the record’s most satisfying tunes, including the whimsical art-pop odyssey “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey,” back-porch acoustic ditty “Heart of the Country” and piano-pop oddity “Monkberry Moon Delight.” —Ryan Reed

Paul McCartney could have formed the ultimate supergroup following the Beatles’ split, but he consciously aimed to sidestep such a high-profile venture. “I was looking for a new band rather than the Blind Faith thing, so I didn’t really want heavyweights,” he told Billboard in 2001, recalling his philosophy in the Ram era. That album, arriving one year after his homespun solo debut (and just ahead of his venture with Wings), was his first with a band mentality: Then-wife Linda McCartney adds charmingly rough-hewn harmonies throughout—and even co-writes some of the record’s most satisfying tunes, including the whimsical art-pop odyssey “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey,” back-porch acoustic ditty “Heart of the Country” and piano-pop oddity “Monkberry Moon Delight.” —Ryan Reed Before Jethro Tull formed in the late ’60s, it’s doubtful that anyone could have imagined the flute making an aggressive sound. Aqualung, the band’s fourth album and the best-selling of its long career, utilized the instrument’s fluttery quality as a vehicle for frontman/flautist Ian Anderson’s anger and intellectual acuity. Prior to this point, the English outfit had established itself as one of the faces of the then-burgeoning progressive rock movement, setting itself apart with a sound that was burlier and more blues-centered than its peers. With Aqualung, though, Anderson, longtime guitarist Martin Barre and their cohorts beefed up their style even further, letting the psychedelic elements recede somewhat in favor of a proto-metal approach that put them in the same stylistic ballpark as Deep Purple and Led Zeppelin. Even though the album features several softer, more intricate sections (the three-song stretch of “Cheap Day Return,” “Mother Goose” and “Wond’ring Aloud”), two of its most iconic guitar riffs (“My God” and the title track) could easily have tickled Beavis and Butt-head’s fancy two decades years later. A scathing indictment on organized religion, Aqualung paints an almost Dickensian picture of English life that’s as compelling—and timeless—as it is dreary. —Saby Reyes-Kulkarni

Before Jethro Tull formed in the late ’60s, it’s doubtful that anyone could have imagined the flute making an aggressive sound. Aqualung, the band’s fourth album and the best-selling of its long career, utilized the instrument’s fluttery quality as a vehicle for frontman/flautist Ian Anderson’s anger and intellectual acuity. Prior to this point, the English outfit had established itself as one of the faces of the then-burgeoning progressive rock movement, setting itself apart with a sound that was burlier and more blues-centered than its peers. With Aqualung, though, Anderson, longtime guitarist Martin Barre and their cohorts beefed up their style even further, letting the psychedelic elements recede somewhat in favor of a proto-metal approach that put them in the same stylistic ballpark as Deep Purple and Led Zeppelin. Even though the album features several softer, more intricate sections (the three-song stretch of “Cheap Day Return,” “Mother Goose” and “Wond’ring Aloud”), two of its most iconic guitar riffs (“My God” and the title track) could easily have tickled Beavis and Butt-head’s fancy two decades years later. A scathing indictment on organized religion, Aqualung paints an almost Dickensian picture of English life that’s as compelling—and timeless—as it is dreary. —Saby Reyes-Kulkarni  T.Rex’s sixth record would be worth talking about even if it was a collection of bad Monkees covers, based solely on the sheer awesomeness of its cover art. If that doesn’t make you want to play the electric guitar, there is something wrong with you. Fortunately, Marc Bolan brought the tunes to back it up. “Bang A Gong” and “Jeepster” are the hits, and great ones at that, but spaced-out acoustic numbers like “Cosmic Dancer” and “Planet Queen” and the fuzzy blues riffs of “Lean Woman Blues” give the album its depth and diversity. Add in lyrics about flying saucers, girls and cars, and glam rock has never sounded so weird and wonderful. —Charlie Duerr

T.Rex’s sixth record would be worth talking about even if it was a collection of bad Monkees covers, based solely on the sheer awesomeness of its cover art. If that doesn’t make you want to play the electric guitar, there is something wrong with you. Fortunately, Marc Bolan brought the tunes to back it up. “Bang A Gong” and “Jeepster” are the hits, and great ones at that, but spaced-out acoustic numbers like “Cosmic Dancer” and “Planet Queen” and the fuzzy blues riffs of “Lean Woman Blues” give the album its depth and diversity. Add in lyrics about flying saucers, girls and cars, and glam rock has never sounded so weird and wonderful. —Charlie Duerr According to the man himself, Miles Davis intended Live/Evil to be a kind of spiritual sequel to his groundbreaking Bitches Brew. But while they share some of the same sonic DNA and personnel, the feeling of this album is somehow darker and more menacing—and, at times, soulful and uplifting. The double LP combines studio work featuring Brazilian composer Hermeto Pascoal with some live sessions captured in Washington DC in 1970. With Teo Macero’s sure editing hands, the two elements blend together seamlessly, hiding yet emphasizing the threads connecting Davis’ interest in hard-charging funk, freeform expression and Latin groove. Everyone involved responds to the call with a wild-eyed joy or sweaty fury, but listen closely for saxophonist Gary Bartz projecting his solos to a far off planet and guitarist John McLaughlin’s unbound assault. They help pull something deep and emotionally charged out of Davis throughout this blistering, beautiful album. — Robert Ham

According to the man himself, Miles Davis intended Live/Evil to be a kind of spiritual sequel to his groundbreaking Bitches Brew. But while they share some of the same sonic DNA and personnel, the feeling of this album is somehow darker and more menacing—and, at times, soulful and uplifting. The double LP combines studio work featuring Brazilian composer Hermeto Pascoal with some live sessions captured in Washington DC in 1970. With Teo Macero’s sure editing hands, the two elements blend together seamlessly, hiding yet emphasizing the threads connecting Davis’ interest in hard-charging funk, freeform expression and Latin groove. Everyone involved responds to the call with a wild-eyed joy or sweaty fury, but listen closely for saxophonist Gary Bartz projecting his solos to a far off planet and guitarist John McLaughlin’s unbound assault. They help pull something deep and emotionally charged out of Davis throughout this blistering, beautiful album. — Robert Ham Following the excesses of Ummagumma and Atom Heart Mother, Pink Floyd retreated to simply being a band on Meddle, with no distracting orchestras, choirs, or wildlife noises. All but one of the songs is credited to multiple members of the band, suggesting a conscious effort to work as a unit instead of as four individuals, and the change in mission is immediately evident on “One of These Days,” arguably their best opener. Roger Waters’ rumbling bass sutures the song together, generating a sinister momentum that recalls some of their earlier, more streamlined instrumentals. Of course the 20-minute closer doesn’t need to be that long, but there are enough big moments that it never becomes tedious. The real star of Meddle is David Gilmour, whose guitar shapes most of these songs. He scribbles furiously over “One of These Days,” sketches out crisp blues-based riffs on “Fearless,” and adorns Waters’ jazzbo “St. Tropez” with jazzy licks. His style is multivaried and unpredictable, deploying earthy rhythms and majestic solos with equal command yet never sounding as showy as some of his blues-rock contemporaries. With Gilmour taking a more prominent role, Meddle transitions easily, even gracefully between hurried jams and hushed folk, between loud and quiet, revealing a band finally mastering dynamics and making their best album since The Piper at the Gates of Dawn. —Stephen Deusner

Following the excesses of Ummagumma and Atom Heart Mother, Pink Floyd retreated to simply being a band on Meddle, with no distracting orchestras, choirs, or wildlife noises. All but one of the songs is credited to multiple members of the band, suggesting a conscious effort to work as a unit instead of as four individuals, and the change in mission is immediately evident on “One of These Days,” arguably their best opener. Roger Waters’ rumbling bass sutures the song together, generating a sinister momentum that recalls some of their earlier, more streamlined instrumentals. Of course the 20-minute closer doesn’t need to be that long, but there are enough big moments that it never becomes tedious. The real star of Meddle is David Gilmour, whose guitar shapes most of these songs. He scribbles furiously over “One of These Days,” sketches out crisp blues-based riffs on “Fearless,” and adorns Waters’ jazzbo “St. Tropez” with jazzy licks. His style is multivaried and unpredictable, deploying earthy rhythms and majestic solos with equal command yet never sounding as showy as some of his blues-rock contemporaries. With Gilmour taking a more prominent role, Meddle transitions easily, even gracefully between hurried jams and hushed folk, between loud and quiet, revealing a band finally mastering dynamics and making their best album since The Piper at the Gates of Dawn. —Stephen Deusner Hunky Dory remains Bowie’s most consistently enjoyable album. The opening track and lead-off single, “Changes,” was reportedly written as a parody of nightclub songs. Considering the chameleon-like nature Bowie’s career would take, hoping from one musical persona and one genre to the next, lines like “Changes are taking the pace I’m going through” make the song feel less like a pop single and more like an artistic manifesto. Elsewhere, his penchant for sweeping, cabaret-esque theatricality has never been more apparent than on the surreal song, “Life on Mars.” Beginning with Bowie wailing over a lonely piano, the track quickly builds in intensity, adding a soaring string section that gives the track its Broadway-worthy punctuation. Written in honor of The Velvet Underground and Lou Reed, “Queen Bitch” introduced the kind of thrashy Mick Ronson guitar riff that helped characterize some of Bowie’s later glam-rock numbers. Clocking in at just over three minutes, the song stands as perhaps the most infectiously catchy song in an album filled with them. —Mark Rozeman

Hunky Dory remains Bowie’s most consistently enjoyable album. The opening track and lead-off single, “Changes,” was reportedly written as a parody of nightclub songs. Considering the chameleon-like nature Bowie’s career would take, hoping from one musical persona and one genre to the next, lines like “Changes are taking the pace I’m going through” make the song feel less like a pop single and more like an artistic manifesto. Elsewhere, his penchant for sweeping, cabaret-esque theatricality has never been more apparent than on the surreal song, “Life on Mars.” Beginning with Bowie wailing over a lonely piano, the track quickly builds in intensity, adding a soaring string section that gives the track its Broadway-worthy punctuation. Written in honor of The Velvet Underground and Lou Reed, “Queen Bitch” introduced the kind of thrashy Mick Ronson guitar riff that helped characterize some of Bowie’s later glam-rock numbers. Clocking in at just over three minutes, the song stands as perhaps the most infectiously catchy song in an album filled with them. —Mark Rozeman Tago Mago is peak Can, and the pinnacle not just of “krautrock” or kosmiche Muzik but perhaps of psychedelic rock as a whole. Can parlayed their instrumental virtuosity and avant garde inclinations into something startlingly new and unthinkable with this double album, as Holger Czukay’s editing experiments propelled the band to the outer reaches of what could be considered rock music. Although it starts off with an experimental but recognizable take on familiar rock, funk and jazz concepts, by the second record it leaves traditional song structure behind. The tracks sprawl out to biblical lengths, and become adventures in sound and atmosphere, with Damo Suzuki’s ghostly whispers and shrieks enhancing its otherworldly vibe. It’s not particularly challenging if you’ve listened to some of the noise, drone and experimental music that it’s influenced over the last 50 years, but if you’re coming to Tago Mago straight from some of the other records on this list, it might feel a bit like the outer reaches of the cosmos suddenly bursting out of your earthbound noggin. —Garrett Martin

Tago Mago is peak Can, and the pinnacle not just of “krautrock” or kosmiche Muzik but perhaps of psychedelic rock as a whole. Can parlayed their instrumental virtuosity and avant garde inclinations into something startlingly new and unthinkable with this double album, as Holger Czukay’s editing experiments propelled the band to the outer reaches of what could be considered rock music. Although it starts off with an experimental but recognizable take on familiar rock, funk and jazz concepts, by the second record it leaves traditional song structure behind. The tracks sprawl out to biblical lengths, and become adventures in sound and atmosphere, with Damo Suzuki’s ghostly whispers and shrieks enhancing its otherworldly vibe. It’s not particularly challenging if you’ve listened to some of the noise, drone and experimental music that it’s influenced over the last 50 years, but if you’re coming to Tago Mago straight from some of the other records on this list, it might feel a bit like the outer reaches of the cosmos suddenly bursting out of your earthbound noggin. —Garrett Martin At a 1968 press conference announcing the formation of Apple Corps., The Beatles were asked about their favorite American artist and group. The Fab Four answered “Nilsson” to both questions. Harry Nilsson may have been a one-man operation, but it’s easy to mistake his perfectly harmonized, multi-tracked vocals for a whole group of talented singers. By 1970, Nilsson had already recorded what would become his most famous songs (“One” and “Everybody’s Talkin’”), but his best album would come a year later with Nilsson Schmilsson. On “Early in the Morning,” the singer shows off his skills as a true melodist, while “Jump into the Fire” is a blistering rock ‘n’ roll tune. Nilsson’s cover of Badfinger’s ballad “Without You” serves as the most heartbreakingly beautiful moment on the record for which he took home the Grammy for Best Male Pop Vocal. But count on Nilsson to provide a lighthearted counterpoint to melancholy with one of the record’s most memorable moments, “Coconut.” —Wyndham Wyeth

At a 1968 press conference announcing the formation of Apple Corps., The Beatles were asked about their favorite American artist and group. The Fab Four answered “Nilsson” to both questions. Harry Nilsson may have been a one-man operation, but it’s easy to mistake his perfectly harmonized, multi-tracked vocals for a whole group of talented singers. By 1970, Nilsson had already recorded what would become his most famous songs (“One” and “Everybody’s Talkin’”), but his best album would come a year later with Nilsson Schmilsson. On “Early in the Morning,” the singer shows off his skills as a true melodist, while “Jump into the Fire” is a blistering rock ‘n’ roll tune. Nilsson’s cover of Badfinger’s ballad “Without You” serves as the most heartbreakingly beautiful moment on the record for which he took home the Grammy for Best Male Pop Vocal. But count on Nilsson to provide a lighthearted counterpoint to melancholy with one of the record’s most memorable moments, “Coconut.” —Wyndham Wyeth One year for my birthday, one of my best friends bought me two very different live albums. One was Ben Folds Live! and the other was At Fillmore East. Up until then, I had never really been a fan of live recordings. I mistakenly thought that all live songs should sound just like their studio-recorded counterparts. I also hadn’t been to many concerts at that point in my life, so I didn’t understand there is a certain energy that is trying to be captured with live albums. But I was willing to give At Fillmore East a try at the recommendation of my friend, especially because I had recently gained interest in blues music, and I was relatively unfamiliar with The Allman Brothers. My mind was blown. I couldn’t even begin to comprehend Duane Allman’s gut-wrenching slide-guitar work, and songs like the near 20-minute jams “You Don’t Love Me” and the album closer, “Whipping Post,” begged for repeated listens, despite their length. This can be heard near the end of the former track when the band slows down, gliding into the “Joy to the World” section, and someone in the audience emphatically yells out, “Play all night!” At Fillmore East captures the talent of a band in its heyday that not only played well, but played well together, showcasing the group’s vigor, exquisite timing and precision in what may be the greatest live album of all time. —Wyndham Wyeth

One year for my birthday, one of my best friends bought me two very different live albums. One was Ben Folds Live! and the other was At Fillmore East. Up until then, I had never really been a fan of live recordings. I mistakenly thought that all live songs should sound just like their studio-recorded counterparts. I also hadn’t been to many concerts at that point in my life, so I didn’t understand there is a certain energy that is trying to be captured with live albums. But I was willing to give At Fillmore East a try at the recommendation of my friend, especially because I had recently gained interest in blues music, and I was relatively unfamiliar with The Allman Brothers. My mind was blown. I couldn’t even begin to comprehend Duane Allman’s gut-wrenching slide-guitar work, and songs like the near 20-minute jams “You Don’t Love Me” and the album closer, “Whipping Post,” begged for repeated listens, despite their length. This can be heard near the end of the former track when the band slows down, gliding into the “Joy to the World” section, and someone in the audience emphatically yells out, “Play all night!” At Fillmore East captures the talent of a band in its heyday that not only played well, but played well together, showcasing the group’s vigor, exquisite timing and precision in what may be the greatest live album of all time. —Wyndham Wyeth Leonard Cohen left a body of work that can stand beside any songwriter in the English language. He’s been given every award and title that official bodies have to offer, and his songs have been endlessly covered, some of them to the point of cliché, but there’s a good reason for that: Cohen has contributed to the canon, he’s expanded the songbook, he’s written the type of songs that people just know without being quite sure how they know them. The opening track on Songs of Love and Hate, “Avalanche,” certainly transmits the feeling of hate, but where is that hate being directed? Is it coming from “this hunchback at which you stare” or is it being directed toward him? The perspective seems to shift throughout the tune as Cohen picks himself into a dizzying spiral on his classical guitar. The song ushers us into Cohen’s darkest and most visionary record with a singular image of elevating the grotesque. The twisted masterpiece “Dress Rehearsal Rag” is Cohen’s most underrated song by far. He famously said of it: “I didn’t write that song, I suffered it.” The suffering comes through to the listener as a harrowing nightmare while also being one of Cohen’s greatest moments of comic grotesquery. The entire album is one of Cohen’s most sparingly arranged records until the monster track “Diamonds in the Mine” jumps out with his uncharacteristically maniacal vocal performance, along with a demented reggae feel that adds a sarcastic note to an already bleak and merciless chorus. With each verse Cohen sounds more and more unhinged until by the end he is literally vamping growls. Elsewhere he leans on his background in poetry, as on “Love Calls You By Your Name.” Each verse puts the listener “here, right here” between two seemingly inseparable images with verses that are occasionally paradoxical, yet all totally free of cliché, and the result is like a zen mental exercise of the type of Cohen famously retreated into later in life. He borrows a technique that stretches back all the way to the invention of the English-language novel for “Famous Blue Raincoat” which, like a few of his greatest tunes, centers on a love triangle. The lasting visual of the lover’s “famous blue raincoat, torn at the shoulder” is the type of crushing memory that shows Cohen’s profound understanding of the workings of the mind. —Nate Logsdon

Leonard Cohen left a body of work that can stand beside any songwriter in the English language. He’s been given every award and title that official bodies have to offer, and his songs have been endlessly covered, some of them to the point of cliché, but there’s a good reason for that: Cohen has contributed to the canon, he’s expanded the songbook, he’s written the type of songs that people just know without being quite sure how they know them. The opening track on Songs of Love and Hate, “Avalanche,” certainly transmits the feeling of hate, but where is that hate being directed? Is it coming from “this hunchback at which you stare” or is it being directed toward him? The perspective seems to shift throughout the tune as Cohen picks himself into a dizzying spiral on his classical guitar. The song ushers us into Cohen’s darkest and most visionary record with a singular image of elevating the grotesque. The twisted masterpiece “Dress Rehearsal Rag” is Cohen’s most underrated song by far. He famously said of it: “I didn’t write that song, I suffered it.” The suffering comes through to the listener as a harrowing nightmare while also being one of Cohen’s greatest moments of comic grotesquery. The entire album is one of Cohen’s most sparingly arranged records until the monster track “Diamonds in the Mine” jumps out with his uncharacteristically maniacal vocal performance, along with a demented reggae feel that adds a sarcastic note to an already bleak and merciless chorus. With each verse Cohen sounds more and more unhinged until by the end he is literally vamping growls. Elsewhere he leans on his background in poetry, as on “Love Calls You By Your Name.” Each verse puts the listener “here, right here” between two seemingly inseparable images with verses that are occasionally paradoxical, yet all totally free of cliché, and the result is like a zen mental exercise of the type of Cohen famously retreated into later in life. He borrows a technique that stretches back all the way to the invention of the English-language novel for “Famous Blue Raincoat” which, like a few of his greatest tunes, centers on a love triangle. The lasting visual of the lover’s “famous blue raincoat, torn at the shoulder” is the type of crushing memory that shows Cohen’s profound understanding of the workings of the mind. —Nate Logsdon Bill Withers would have been a great songwriter no matter where or how he grew up. He worked so hard at carving out catchy melodies and chorus aphorisms that they would have resonated with listeners in any case. But what gave Withers’ music its distinctive flavor was his background. The 20th century had many brilliant songwriters who were raised black and urban, white and rural or white and urban, but Withers was one of very few who were raised black and rural. He grew up in Beckley, West Virginia, and it was there he learned the cadences and vocabulary of African-American blues and gospel, and it was there he learned the value of mountain songs that didn’t need more than one guitar and one voice to get over. On Just As I Am, “Ain’t No Sunshine,” declared, “It’s not warm when she’s away,”—the inverse of Smokey Robinson’s “My Girl,” which announced, “I’ve got sunshine on a cloudy day.” These two songwriters spearheaded a golden era of poetic soul music in the ’60s and ’70s, leading the way for fellow lyricists such as Curtis Mayfield, Sly Stone, Earl King, Oscar Brown Jr., Don Bryant and Marvin Gaye. It was an era when the audience’s hunger for lyrics with substance met a generation of wordsmiths willing to supply the nutrition. The best example of Withers’ visual songwriting is “Grandma’s Hands.” He describes those two swollen hands clapping in a West Virginia church, slapping a tambourine against one palm, handing a child a piece of candy, lifting the chin of a sobbing girl and picking up a boy who’s fallen. The subject matter is churches and small towns, and so is the sound of the music. —Geoffrey Himes

Bill Withers would have been a great songwriter no matter where or how he grew up. He worked so hard at carving out catchy melodies and chorus aphorisms that they would have resonated with listeners in any case. But what gave Withers’ music its distinctive flavor was his background. The 20th century had many brilliant songwriters who were raised black and urban, white and rural or white and urban, but Withers was one of very few who were raised black and rural. He grew up in Beckley, West Virginia, and it was there he learned the cadences and vocabulary of African-American blues and gospel, and it was there he learned the value of mountain songs that didn’t need more than one guitar and one voice to get over. On Just As I Am, “Ain’t No Sunshine,” declared, “It’s not warm when she’s away,”—the inverse of Smokey Robinson’s “My Girl,” which announced, “I’ve got sunshine on a cloudy day.” These two songwriters spearheaded a golden era of poetic soul music in the ’60s and ’70s, leading the way for fellow lyricists such as Curtis Mayfield, Sly Stone, Earl King, Oscar Brown Jr., Don Bryant and Marvin Gaye. It was an era when the audience’s hunger for lyrics with substance met a generation of wordsmiths willing to supply the nutrition. The best example of Withers’ visual songwriting is “Grandma’s Hands.” He describes those two swollen hands clapping in a West Virginia church, slapping a tambourine against one palm, handing a child a piece of candy, lifting the chin of a sobbing girl and picking up a boy who’s fallen. The subject matter is churches and small towns, and so is the sound of the music. —Geoffrey Himes Tapestry was nothing less than the sound of a generation growing up. I was 13 the first time I heard “It’s Too Late.” It shook me, because it was one of the first pop songs I can remember about love dying, divorce, etc. Sure, there were lots of songs about young love not prevailing —“Breaking Up Is Hard To Do,” that kind of thing. But Carole King sang about adult love not prevailing —about heartbreak and compromise being permanent features of the grownup landscape. Tapestry has always been the ultimate chick album. But more than that, it was a mature album, and the world it described was both as exotic as Tahiti, and as familiar as my parents’ bedroom, down the hall. —Tom Junod

Tapestry was nothing less than the sound of a generation growing up. I was 13 the first time I heard “It’s Too Late.” It shook me, because it was one of the first pop songs I can remember about love dying, divorce, etc. Sure, there were lots of songs about young love not prevailing —“Breaking Up Is Hard To Do,” that kind of thing. But Carole King sang about adult love not prevailing —about heartbreak and compromise being permanent features of the grownup landscape. Tapestry has always been the ultimate chick album. But more than that, it was a mature album, and the world it described was both as exotic as Tahiti, and as familiar as my parents’ bedroom, down the hall. —Tom Junod One of The Rolling Stones’ best LPs, Sticky Fingers was the first release on the band’s own Rolling Stones Records and the first full album contribution from guitarist Mick Taylor. Back in 2012, Paste placed seven Sticky Fingers tracks on our list of

One of The Rolling Stones’ best LPs, Sticky Fingers was the first release on the band’s own Rolling Stones Records and the first full album contribution from guitarist Mick Taylor. Back in 2012, Paste placed seven Sticky Fingers tracks on our list of  It’s difficult to call Led Zeppelin IV the greatest “hard rock” album in music history—only because (in spite of its legacy) it’s much, much more than a “hard rock” album. Led, as always, by the black-magic mojo of guitarist-producer Jimmy Page, Led Zep truly indulged in 1971, branching out into extended progressive-rock (the sweeping, majestic epic “Stairway to Heaven”), medieval folk (the witchy “The Battle of Evermore”) and psychedelic balladry (the emotional centerpiece, “Going to California”), in addition to their trademark electrified blues (“Rock and Roll,” “Black Dog,” “Four Sticks,” “When the Levee Breaks”). Eight tracks, eight classics: It’s one of the greatest rock albums ever recorded, whatever it is. —Ryan Reed

It’s difficult to call Led Zeppelin IV the greatest “hard rock” album in music history—only because (in spite of its legacy) it’s much, much more than a “hard rock” album. Led, as always, by the black-magic mojo of guitarist-producer Jimmy Page, Led Zep truly indulged in 1971, branching out into extended progressive-rock (the sweeping, majestic epic “Stairway to Heaven”), medieval folk (the witchy “The Battle of Evermore”) and psychedelic balladry (the emotional centerpiece, “Going to California”), in addition to their trademark electrified blues (“Rock and Roll,” “Black Dog,” “Four Sticks,” “When the Levee Breaks”). Eight tracks, eight classics: It’s one of the greatest rock albums ever recorded, whatever it is. —Ryan Reed  It’s kinda hard to believe Who’s Next, The Who’s rawest, most powerful and perfect album, came out in 1971. Barely out of the flowery 1960s (and fresh off their psychedelic—and cluttered—rock-opera, Tommy), guitarist/songwriter/vocalist Pete Townshend set to work on Lifehouse, a futuristic follow-up concept album so epic in its proposed scope, it made Tommy’s deaf-dumb-blind-pinball-playing narrative look meager by comparison. While Townshend’s outlandish ideas eventually got away from him, it worked out for the best: Who’s Next, a bastardized version of the original concept album, is hard rock’s definitive masterpiece, crammed top-to-bottom with classics like “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” “Behind Blue Eyes,” “Bargain,” “Baba O’Riley,” and, well, everything else. —Ryan Reed

It’s kinda hard to believe Who’s Next, The Who’s rawest, most powerful and perfect album, came out in 1971. Barely out of the flowery 1960s (and fresh off their psychedelic—and cluttered—rock-opera, Tommy), guitarist/songwriter/vocalist Pete Townshend set to work on Lifehouse, a futuristic follow-up concept album so epic in its proposed scope, it made Tommy’s deaf-dumb-blind-pinball-playing narrative look meager by comparison. While Townshend’s outlandish ideas eventually got away from him, it worked out for the best: Who’s Next, a bastardized version of the original concept album, is hard rock’s definitive masterpiece, crammed top-to-bottom with classics like “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” “Behind Blue Eyes,” “Bargain,” “Baba O’Riley,” and, well, everything else. —Ryan Reed Funkadelic’s Maggot Brain opens with a kaleidoscopic 10-minute suite that ruminates on the pratfalls of drowning in one’s own shit. It only gets weirder from there. Clinton apparently didn’t think much of sampling infant coos on the implacable call to arms “Wars of Armageddon;”“You and Your Folks, Me and My Folks” bedecks a classic 20th Century parable with rolling juke pianos and static flourishes of electronic organ. “Can You Get to That” seesaws on the dueling voices of Gary Snider and Pat Lewis, taking on the air of a violent fantasia. Maggot Brain doesn’t always make sense, either technically or thematically, but it’s big and florid and overwhelming—imagine staring into a gilded, floor-to-ceiling mirror while on DMT. —M.T. Richards

Funkadelic’s Maggot Brain opens with a kaleidoscopic 10-minute suite that ruminates on the pratfalls of drowning in one’s own shit. It only gets weirder from there. Clinton apparently didn’t think much of sampling infant coos on the implacable call to arms “Wars of Armageddon;”“You and Your Folks, Me and My Folks” bedecks a classic 20th Century parable with rolling juke pianos and static flourishes of electronic organ. “Can You Get to That” seesaws on the dueling voices of Gary Snider and Pat Lewis, taking on the air of a violent fantasia. Maggot Brain doesn’t always make sense, either technically or thematically, but it’s big and florid and overwhelming—imagine staring into a gilded, floor-to-ceiling mirror while on DMT. —M.T. Richards With the world crumbling around Sly Stone—including dissolving relationships and political pressure from the Black Panther Party—he and his group nose-dived into the era’s drug culture. During this period, they picked apart their already-successful psych-soul blueprint to make a darker, more somber record. Stone teetered on the edge during the making of There’s a Riot Goin’ On, holding on long enough to create one of the formative post-flower-power psychedelic albums. Within this work, Sly and the Family Stone offer a disillusioned look at the changing landscapes around them, sharing a loosely conceptualized and cynical outlook depicting the signs of the times. —Max Blau

With the world crumbling around Sly Stone—including dissolving relationships and political pressure from the Black Panther Party—he and his group nose-dived into the era’s drug culture. During this period, they picked apart their already-successful psych-soul blueprint to make a darker, more somber record. Stone teetered on the edge during the making of There’s a Riot Goin’ On, holding on long enough to create one of the formative post-flower-power psychedelic albums. Within this work, Sly and the Family Stone offer a disillusioned look at the changing landscapes around them, sharing a loosely conceptualized and cynical outlook depicting the signs of the times. —Max Blau It’s no coincidence that the title of Mitchell’s fourth album echoes the title of Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, for the singer-songwriter similarly uses modal minimalism and augmented chords to lend a translucent glow to romantic melancholy. Written in the wake of her break-up with longtime lover Graham Nash, these songs have such sturdy melodies and stories that they can afford to be stripped down and stripped bare in the studio, often to nothing more than Mitchell’s soprano and acoustic guitar, dulcimer or piano. The results include her catchiest tune since “Both Sides Now” (“Carey”) and the decade’s best new Christmas song (“The River”). —Geoffrey Himes

It’s no coincidence that the title of Mitchell’s fourth album echoes the title of Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, for the singer-songwriter similarly uses modal minimalism and augmented chords to lend a translucent glow to romantic melancholy. Written in the wake of her break-up with longtime lover Graham Nash, these songs have such sturdy melodies and stories that they can afford to be stripped down and stripped bare in the studio, often to nothing more than Mitchell’s soprano and acoustic guitar, dulcimer or piano. The results include her catchiest tune since “Both Sides Now” (“Carey”) and the decade’s best new Christmas song (“The River”). —Geoffrey Himes If Marvin Gaye had been a better athlete—or less obstinate—we might not have gotten one of the greatest albums of all time. In 1970, after the death of his musical partner Tammi Terrell, the Motown singer tried out for the Detroit Lions. When he returned to music, it was on his own terms. What’s Going On was an epic response to his brother Frankie’s letters from Vietnam—politically charged and musically ambitious, a soul album with jazz time signatures and classical instrumentation. The album’s posture was one of lament for the way things were rather than an angry protest, making the message both clear and difficult to tune out. It was such a departure from Gaye’s radio-friendly pop that his brother-in-law Berry Gordy Jr. initially refused to release it on Motown Records. Gaye had produced the album himself with backing from the Funk Brothers, and presented it as a complete nine-song suite. It was a singular vision and one that hasn’t lost any of its power over time. —Josh Jackson

If Marvin Gaye had been a better athlete—or less obstinate—we might not have gotten one of the greatest albums of all time. In 1970, after the death of his musical partner Tammi Terrell, the Motown singer tried out for the Detroit Lions. When he returned to music, it was on his own terms. What’s Going On was an epic response to his brother Frankie’s letters from Vietnam—politically charged and musically ambitious, a soul album with jazz time signatures and classical instrumentation. The album’s posture was one of lament for the way things were rather than an angry protest, making the message both clear and difficult to tune out. It was such a departure from Gaye’s radio-friendly pop that his brother-in-law Berry Gordy Jr. initially refused to release it on Motown Records. Gaye had produced the album himself with backing from the Funk Brothers, and presented it as a complete nine-song suite. It was a singular vision and one that hasn’t lost any of its power over time. —Josh Jackson