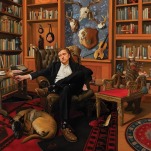

Bonnie Raitt

While Bonnie Raitt was preparing, recording, releasing and touring behind her 15th studio album, Souls Alike, she lost both her parents. Her mother, Marjorie Goddard, died from Alzheimer’s on July 2, 2004, and her father, the Broadway star John Raitt, died of pneumonia on February 20, 2005. The younger Raitt was able to take time from studio sessions, meetings and tour dates to say goodbye to each parent. What she didn’t have time for was properly mourning them. To further complicate matters, her big brother Steve, a Minnesota sound engineer, had contracted terminal cancer.

“With all that loss not properly processed,” she says soberly, “I had to take some time off. You need time to grieve, and you can’t be running a big operation while you’re doing that. I did that 2009 tour with Taj Mahal and a few one-month or one-week runs, but that’s not the same as planning a new album and then touring to support it. That’s all-consuming. So I took some years off.”

That’s why Raitt seemed to disappear for seven years, but now she’s back with her 16th studio album, Slipstream, on her own, brand-new label, Redwing Records. It’s only the third company she’s recorded for in 40 years. The 1971-1986 Warner Bros. years were an era of deep folk and blues roots that made her a critical favorite, if also a commercial also-ran. The 1991-2005 Capitol years marked the triumphant reward for that good work in the form of top-10 hits and Grammy Awards. The Redwing years begin now with a disc split between a continuation of her old sound and the exploration of a very different one.

Seven of the tracks on Slipstream were produced by Raitt backed by her crackerjack road band: ex-Hendrix keyboardist Mike Finnigan, ex-Beach Boys drummer Ricky Fataar, ex-Bruce Hornsby and the Range guitarist George Marinelli and bassist John “Hutch” Hutchinson. The songwriters are just as familiar (NRBQ’s Al Anderson, Ireland’s Paul Brady, ex-husband Michael O’Keefe and Sea Level’s Randall Bramblett) and so is the sound: a funky brand of roots-rock led by Raitt’s slide guitar and sly but powerful alto.

The other four tracks, though, were produced by Joe Henry with a band led by jazz guitarists Bill Frisell and Greg Leisz; two of the songs were written by Bob Dylan, and the other two by Henry. The result is a kind of Americana-jazz that is understated and moody, full of odd, reverberating chords. It’s unlike anything Raitt has done before.

“Because I’d been gone a long time,” Raitt says. “I wanted to do some songs in the old style to let the fans know I hadn’t changed that much. But I also wanted to try something new, because that makes it more interesting for them—and for me too.

“Joe Henry was at the top of my list of people to reach out to, because he had produced several friends of mine. I really like his songwriting, and I had two songs of his I knew I wanted to do. I knew I wanted to do the more rocking and blues side of me with my band, because I didn’t want to abandon them. We’re together all the time on the road, and I wanted to keep that juice going.”

None of the songs on Slipstream directly address the themes of death and loss, but there are subtle allusions. “You took a part of me that I really miss; I keep asking myself, ‘How long can it go on like this?’” she sings over Frisell’s ghostly guitar echoes on Dylan’s “Million Miles.” Above Leisz’s chiming steel guitar on Dylan’s “Standing in the Doorway,” she laments, “I hear the church bells ringing in the yard; wonder who they’re ringing for?” On Henry’s “God Only Knows,” accompanied only by Patrick Warren’s stark piano, she sings, “Darkness settles on the ground, leaves the day stumbling blind, coming to a quiet close.” The other tracks are more typical observations on new love, old love, bad love and good love.

“I couldn’t address that loss directly in songs,” she says; “it was too soon to delve into that. I admire that album Rosanne Cash made about her father’s death, but I couldn’t do that now. Maybe later on I will. I do think that life experiences like these make you sing more deeply.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-