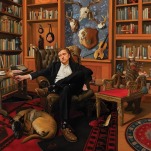

Bruce Cockburn

Like the rest of the world, Bruce Cockburn is pensive these days. Confronted with the sight of tanks rolling through the streets of Baghdad, the politically active, spiritually minded veteran of 27 albums offers a typically challenging analysis: “I don’t know if I believe in the literal existence of Satan,” he offers. “But if he’s real, he’s got to be laughing his head off.” It’s the kind of assessment that isn’t new for Cockburn, one sure to elicit nods of agreement or howls of outrage, depending on his audience’s spiritual and political views.

But Cockburn has never been one to cater to anyone’s expectations. Pegged as a Christian mystic in the ‘70s, Cockburn has confounded all sides of his audience, first with a series of decidedly leftist political albums in the ‘80s, albums antithetical to the conservative Reagan zeitgeist of many of his evangelical followers. The paeans to the Sandinistas and diatribes against the International Monetary Fund won him new followers on the far left, but they too were confounded when Cockburn continued to pursue his spiritual muse, including the release of a 1992 Christmas album that contained fifteen songs about—of all things—Christ. In short, Bruce Cockburn is simply who he is: the creator of some of the most thoughtful, challenging and beautiful songs of the past several decades, a masterful guitarist equally at home with folk, jazz, rock and world music, and a compassionate, caring, restless, ever-searching, world-weary, helpless, socially active, peace-loving, raging bundle of contradictions. Leave your stereotypes at home. You won’t need them on this journey.

Bruce Cockburn has a new album, You’ve Never Seen Everything. The title reflects a theme that echoes through all his albums recorded over a 33-year career. “I’m afraid of repeating myself,” admits Cockburn. “It’s a phobia I have. I never assume I’m going to be able to write another album after I finish one. It’s a gift when I’m able to, and I never take it for granted. If there’s a trick to it at all, it involves approaching life with a sense of openness. If you don’t keep learning and growing, you’re going to stagnate.”

He needn’t worry. You’ve Never Seen Everything sounds fresh and timeless, musically adventurous, full of the lyrical insights that distinguish Bruce Cockburn’s best songs. It’s easily one of the highlights of his career. The familiar Cockburn touches are there—Hugh Marsh’s soaring violin work and Colin Linden’s guitar fills, Sam Phillips’ background vocals and Cockburn’s own stinging guitar leads. But he borrows two of the best in the business, bassist Larry Taylor and percussionist Stephen Hodges from Tom Waits’ band, and they contribute supple, sympathetic accompaniment to the most jazz-influenced album of Cockburn’s career.

Even more notable are the contributions of pianist Andy Milne and harmonica player Gregoire Maret. Cockburn met Milne, the leader of avant-garde jazz ensemble Dapp Theory, after one of Cockburn’s New York gigs, and their ensuing collaboration is proof of what can happen when the creative minds of two different generations meet and spark. The interplay is frequently spectacular, as when Cockburn and Milne trade solos on the blistering “Trickle Down,” a polemical rant against voodoo economics featuring some breakneck Milne piano runs. It’s as if Cockburn had recruited a young Bud Powell or Herbie Hancock to the band, and he himself seems as invigorated and astonished at the results as anyone. “He’s really something, isn’t he?” he enthuses. And indeed he is. Maret, also an integral part of Dapp Theory, is just as impressive, and his jazz-inflected harmonica floats in and out of several songs like the ghost of Toots Thielemans. Together they help to shape an album that sounds like nothing that has preceded it in the Cockburn catalogue. Approaching 58, Cockburn has ventured down another delightful and unexpected road. There’s no stagnation in sight.

Bruce Cockburn knows unexpected roads. “You see the extremes of what humans can be,” he wrote in an early ‘80s song called “Rumours of Glory.” He was just summarizing his life story. He may not have seen everything, but he’s seen enough extremes in those 58 years to qualify for “close enough” status. Traveling from Mali to Cambodia, from Guatemala to Kosovo to Mozambique, Bruce Cockburn has chronicled what he’s seen, and how he’s reacted. His most famous reaction, an anguished cry of helplessness and rage at the sight of helicopters crossing the Mexico-Guatemala border to strafe desperate Guatemalan refugees, remains indelible in the memory. You hear the song once and you don’t forget it:

I want to raise every voice

At least I’ve got to try

Every time I think about it

Water rises to my eyes

Situation desperate,

echoes of the victims cry

If I had a rocket launcher

some sonofabitch would die

That one earned Bruce Cockburn a certified hit in 1984, airplay on MTV, and the kind of notoriety that he would probably like to forget: as a form of psychological warfare, the U.S. military played that song in 1989, quite loudly, outside the Vatican Embassy in Panama City during its attempt to oust Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega. Having seen his song twisted into a perverse patriotic anthem, he expresses a certain ambivalence about it these days. He hasn’t performed “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” for several years now, and won’t sing it even if it’s requested, as it inevitably is at his concerts. He’s fearful of the current emotional climate, especially in the United States; he’s worried that people will hear it the wrong way, that they won’t understand, and he doesn’t want to run the risk of feeding a body of emotion that he’d rather not arouse.

“We’re confronted with great darkness as a species right now, as spiritual creatures on this planet,” says Cockburn. “I don’t think it’s hopeless, and I don’t want You’ve Never Seen Everything to make people feel hopeless. But I think we’ve got to call a spade a spade.”

No problem there. Cockburn has never shied away from big pronouncements, and he doesn’t on his latest album either. Beginning his new song “All Our Dark Tomorrows” with the line “The village idiot takes the throne” probably won’t win him an invitation to the White House, but then, he’s probably not fishing for one in the first place. The usual targets—greed, hypocrisy, multinational corporations, the systematic destruction of the environment—come in for their biennial skewering. It would all sound very familiar if Bruce Cockburn wasn’t so creative at finding new ways to spout invective. Then again, there’s this:

The grinding devolution

of the democratic dream

Brings us men in gas masks dancing

while the shells burst

The trouble with normal is

it always gets worse

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-