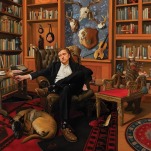

Kate Bollinger Emerges at Long Last

After releasing her first single more than six years ago, the Los Angeles singer-songwriter’s debut is out now. We sat down with her to get the dirt on all things Songs From a Thousand Frames of Mind.

Photo by Leanna Kaiser

Kate Bollinger’s debut album, Songs From a Thousand Frames of Mind, is a summertime sojourn, with sugary choruses wrapped around a warmth you can only get when the sun is beating down. Pressing play on songs like “What’s This About (La La La La)” and “Any Day Now” is like accepting an invitation into laughter and mischief and romance. The record is totally Hollywood, with a treble of excess popping every stitch. Across 40 minutes, the colors burst, especially reds, and a grainy kind of oeuvre unspools merrily while we follow Bollinger’s gentle warble across Tinseltown’s postcard haunts. But not even Bollinger’s declaration that “winter spawns inside of me” at the dawn of Songs From a Thousand Frames of Mind can ice down the putrid stink of the 100-degree heat washed over Los Angeles when I link up with her on a Monday afternoon.

We’re meeting up for a late lunch at an eatery with a name that my sun-baked brain has already purged out of my memory; it’s one of those spots with no air conditioning to be found, because it’s technically an outside restaurant with a roof over it. We play it cool by ordering cold drinks and, in theory, grabbing the best seats in the house: a two-person table stationed in the path of a rusting fan. No dice, it’s actually just pushing warm air in our direction. Maybe there’s a reason why Bollinger and I are the only people there; nobody with any sense would dare boil alive at a brunch spot on a Monday, of all days. My Ohio skin isn’t used to the sores of a West Coast scorcher, but Bollinger is used to it by now.

She moved to Los Angeles from Virginia two years ago, having spent the first eras of her life in and around Charlottesville, where she was raised and, eventually, went to college. At the time of our conversation, Bollinger’s first friend, whom she met when they were both babies, is in town and staying with her. “We were talking about Charlottesville yesterday and trying to describe what’s so amazing about it, because we’re both obsessed with it,” Bollinger explains. “But it’s this unexplainable thing about a town.” Those of us with a casual knowledge about Charlottesville likely remember that the Dave Matthews Band hail from there, but Bollinger contends that the buck doesn’t stop with the “Crash” singer and Kinzie Street Bridge phenomenon. “There was so much cool art and music happening when we were little,” she says. “There was this show house called Magnolia House, there was a venue called Tea Bazaar, the Gravity Lounge—so many venues and kids playing shows and making art.”

The Charlottesville art scene was Bollinger’s introduction to the vocation of playing in bands and writing songs. There was a recurring event called Fridays After Five, where local bands would play at the downtown mall, and the Virginia Film Festival would come to town annually. Both of her brothers played music, and her mom is a music therapist with a focus in children’s music. “She always had a children’s choir that sang on her albums, and I was one of the kids in the chorus,” Bollinger beams. This meant kids were at her house rehearsing all the time, and her family’s basement is where her siblings’ bands would practice. “It was a really loud, chaotic house,” she measures, before pausing. “But in a great way! We had so many pets, too. It was very crazy and free and wild in a way that, looking back, I’m really grateful I had.”

Bollinger’s mom’s work with children was a holistic one that was always imprinting on her attention and affection for music, even if she couldn’t feel the influence of it until adulthood. Her mom worked with a community up in the mountains of Wildcat Hollow near Crozet, leading music therapy groups for adults with developmental disabilities, and Bollinger would go to some of the sessions and sit in on workshops. “It wasn’t something I was consciously learning, but I was seeing that music was helping people access different parts of their brain and access memories and comfort in a really nice way,” she says. On new songs like “God Interlude” and “Postcard From a Cloud,” Bollinger settles into the grace of remembering; “Oh, my friends, how’s it going?” she sings. “I think about you more than I’m showing.”

Bollinger’s first single, “Dreams Before,” came out over six years ago. Ask 10 musicians why it took them over half-a-decade to put out their debut album and you’ll likely get 10 different answers. For Bollinger, it was a product of her self-proclaimed lack of patience. “When I was in high school, I would write a song and be so excited about it that I just wanted to release it immediately,” she explains. “I also move on really quickly from what I’m into to the next thing, so I was making these shorter form projects and wanting to release them. It comes from a place of not wanting to wait for the material for a full-length.” What’s refreshing, though, about Bollinger’s arc is that, despite having dozens of singles and a handful of EPs out in the world already, like the very good I Don’t Wanna Lose and the great Look at it in the Light, Songs From a Thousand Frames of Mind doesn’t blend into the six years of material she’s already collected—standing alone like a proper debut, which, given that there’s no shortage of Kate Bollinger songs already accessible, is no easy feat.

Leading up to the creation of Songs From a Thousand Frames of Mind, Bollinger began collaborating more often. You can hear her on Drugdealer’s “Pictures of You” or Paul Cherry’s “OBO” and “Playroom,” and I even discovered Bollinger’s music for the first time through her inclusion on the Pax song “I’m Not Around.” But as dreamy and memorable as those compositions are, they were never as tectonic as Bollinger’s solo efforts, especially stuff like “Who Am I But Someone” and “No Other Like You.” Even on the EPs she was making back then, which she categorizes as her “feeling around in a dark room, trying to figure out” what she wanted to say, they still sound unequivocally like her. The Drugdealer and Paul Cherry material, good as it all may be, only tells half of the story.

“I definitely found my sound and my songwriting over the course of those years, but I also felt a lack of control with my work,” she says. “When I was recording in high school, and even with ‘Dreams Before’—because I was still writing those songs alone and then bringing them to my friend who was producing—it felt very much like I took an idea from start to finish, that it was a full expression of what I wanted to say. Some of the stuff that I made between now and then feels like I was part of a band. When I was making this album, even though I had somebody produce it, I feel like I took back some control.”

Something I gravitate toward in Bollinger’s work is her voice. It’s feathery and soothing, existing like a balm of sentimentality that reminds me greatly of Michelle Phillips’ singing—a whisper that, on its own, fusses like a lullaby until, once draped in ornate, time-worn textures, becomes something hypnagogic and remarkable. We already know Bollinger’s vocal can flourish in the arena of a duet, paired with masculine voices buffering through the same institutions of rock ‘n’ roll as hers, but Songs From a Thousand Frames of Mind quickly offers a clear picture of another truth: She can absolutely wail on her own, though she’s not ready to leave those tandem harmonies behind just yet, which is why Hannah Cohen shows up perfectly on “Postcard From a Cloud” and “I See It Now.” “I feel, in some ways, like a chameleon,” Bollinger says. “There are so many different eras and styles and ways that I like to write and ways that I like to sing that I think I like being able to do both, because one without the other leaves half of me unexpressed.”

To that measure, it makes sense that Bollinger recorded Songs From a Thousand Frames of Mind with her friends: Adam Brisbin, Matt White, Jacob Grissom, Eli Crews, Sean Mullins, Cohen and Sam Evian, whose West Shokan, New York studio, Flying Cloud Recordings, was where the record came to life in the summer of 2023 (except for “Running,” which was recorded at Flying Cloud two years earlier). The preciousness of having a tight-knit coterie of players like that isn’t something Bollinger takes for granted. “I think that’s also part of why it took me so long to make this album,” she admits. “I spent a lot of time figuring out who I wanted to work with. When I moved [to Los Angeles], I basically spent the first year doing that, trying out different combinations of people and producers and figuring out what worked. And then, of course, I decided to work with the first person I tried recording with three years ago, which is Sam. When I’m trying on a million outfits, I always wear the first thing that I put on.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-