Listening to Neil Young After Coming Out

An ode to a non-binary life, Everybody Knows This is Nowhere, and the joy of coming alive with the weight of Young’s words.

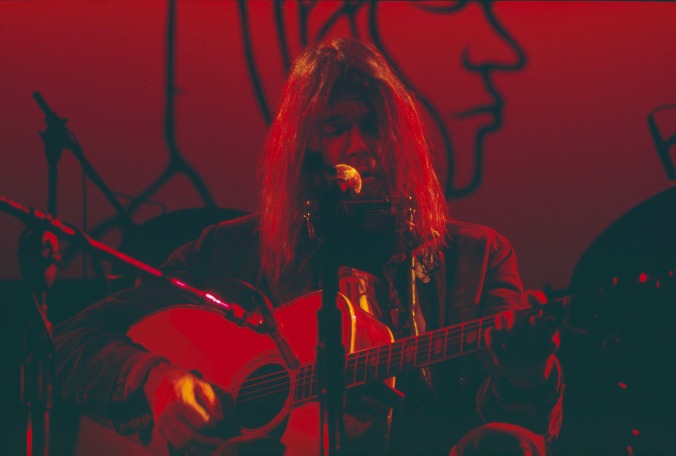

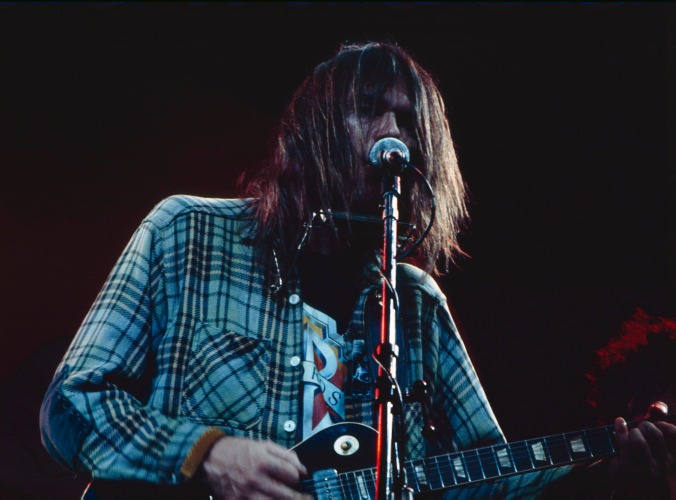

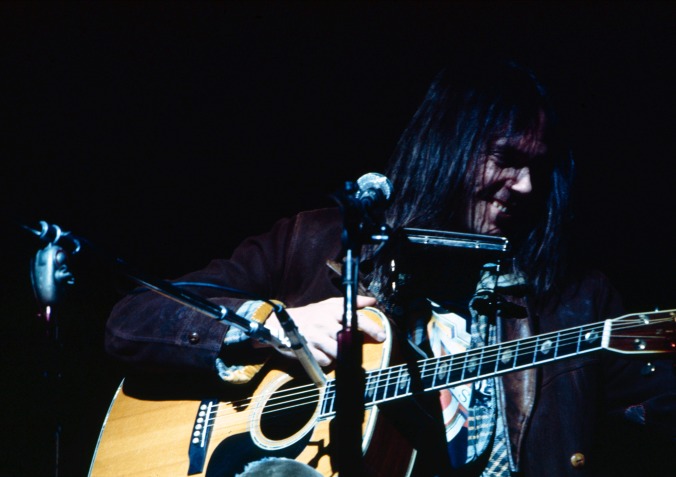

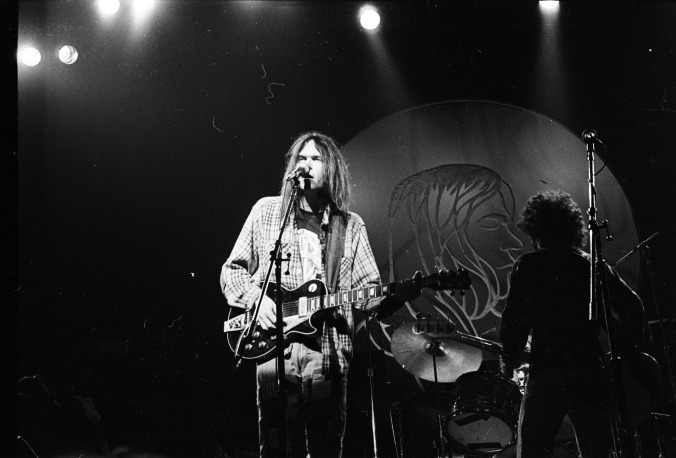

Photos by Legon 108/Shutterstock

Everything good in this world once began with a greatest hits collection. I still remember it vividly, my first taste of freedom. I was newly 16 and newly licensed and newly in love, driving my mom’s old Pontiac across the county while the girl I was crushing on sat in the passenger seat. She held my hand and even took a picture of our fingers intertwined, saving it for a future Instagram post to make us “official.” It was our first date—it was my first date ever—and we did what any teenage couple does: Hit up the Eastwood Mall, a rural Ohio complex with more square-feet than the Mall of America, and aimlessly wander in and out of every store. We didn’t have much money between the two of us, just enough to, maybe, get some sort of food court supper or a tank of gas. After combing every shelf in Hot Topic, Spencer’s and Journey’s, we landed in an FYE and my gaze quickly became affixed on her thumbing through the store’s extensive, endless CD collection.

It was like I had known her forever and not at all, as she pulled out various copies of blink-182 albums and the glint of her nose ring collided with that of the jewel cases. It begged the question of whether or not this is what Macaulay Connor meant when he told Tracy Lord she was “lit from within” in The Philadelphia Story. On the other side of the aisle, I gravitated to the section labeled “NEIL Y UNG” (the “o” had been lost to the sands of time, presumably) and pulled out a used CD titled Greatest Hits. A buddy of mine told me I’d be into Neil, and I’d seen my father get a bit teary-eyed when “Old Man” came on the radio in his truck once. So there it was—16 songs to encapsulate one lifetime, resting beneath a cracked cover and a ripped liner-notes booklet. It would become six of the best dollars I ever spent.

That girl and I, we thought it’d be fun to just turn down a bunch of roads—refusing to use a GPS—and see where we landed. So we played that Neil Young greatest hits CD until it took us someplace new. Of course, neither of us expected to land in Western Pennsylvania, somehow avoiding crossing into the neighboring Keystone State through the turnpike and paying the astronomical tolls. “Down By the River” ripped through the speakers, until the sturdy, raucous backbone of Crazy Horse helped shepherd “Cowgirl in the Sand” into our ears with a menacing, unkempt, quasi-jangly two-part riff—one in the right ear from Neil, one in the left from Danny Whitten. “Hello, ruby in the dust,” Neil greeted us in the second verse, after having bent the car sideways with a Whitten-accented solo. “Has your band begun to rust?”

I had grown up on rock ‘n’ roll—the prophecy of face-melting tempos and prophetic, operatic singing from big-pricked Adonises existing as a tome in my parents’ house. But this was something much different, much rougher around the edges. It sounded like I had felt—ugly. I was slack-jawed and transformed, as if I’d always been searching for that feeling, that sound, that noise. Later, I dropped my date off at her mother’s house, and we shared a hug goodnight and I sped home, hitting rewind on “Down By the River” and letting the blisters guide me across two towns, back to a world I kept hidden from everyone else.

A year earlier, doctors with cold hands diagnosed me with a sex chromosome disorder of the male phenotype—or intersex, to the layman. “Oh, God, I’m a hermaphrodite” was one of the first thoughts that ran through my mind. But I wasn’t that, though the ninth episode Friends’s eighth season would lead you to believe otherwise. I lived the first 15 years of my life as a boy because that is the body I entered this world with. Put my blood under a microscope, though, and you’ll find that the crucial male denominator—that devilish, no-good Y-chromosome—is plum missing from the whole helix. “What the hell does that mean?” was likely my second thought, having just been touched, measured, examined and questioned for nearly two hours in a dim lab room by strangers and then told, bluntly, that my body can’t make its own testosterone. I felt fucked.

There was a moment soon after that, though, when my parents and I sat in an examination room together and listened to an endocrinologist prescribe me testosterone enanthate, that I think about often. You could see it in their faces that something had been taken away from them—perhaps the certainty of their son’s boyhood, which would now exist only through a gel rubbed across his stomach nightly. But now 11 years removed from it all, I think something was given to me then. Maybe it was a life, maybe it was hope. Maybe it was both. Let’s go with both, if only for both’s sake. There is something freeing about your life going into reset, even if the side-effects aren’t particularly copacetic at the time (and likely never will be).

My family kept my hormone therapy a secret until I was in college, when we’d finally reached a point where bringing it up took far less effort than covering it up. I was also writing about it a lot in undergrad workshops—working on what would, eventually, become the manuscript for my first published book—so tip-toeing around the subject everywhere else in life wasn’t worth the hassle. Dorm RAs were doing wellness checks on me for the Coke bottle full of used insulin needles beneath my bed; certainly the inevitable 20 questions from a nosy aunt, too, would pass.

But in high school, you can only hide so much. I walked the halls with giant red welts under my shirt from the gel (which would grow in size, itch and shame years later when I transitioned to needles), yet my voice slowly started to deepen—many, many months after everyone else’s had. No matter how often I tried lifting weights, I couldn’t build muscle mass. My arms and legs were thin like wind chimes; tufts of hair immune from decamping across my face and chest. I didn’t look like the boys in my class, and I certainly didn’t feel like them, either. The first lesson in being intersex is you must come to terms with your own otherness, your own in-betweenness. You can pass for one thing, only to have it ripped away from you by a doctor every six months at a check-up.

When I was a teenager, just wearing the wrong set of clothes got me labeled a fag (in hindsight, they were onto something) in the same way that nosy aunt had, over-and-over again, called me a metrosexual to my face and to my mother’s for years beforehand; the mere thought of even attempting to hold conversations with these people about chromosomes and sex with mutual, well-intentioned nuance felt impossible. And, the very real likelihood of my existence becoming defined by a defense of No, no, I promise I have a cock every waking second of my remaining three years in school was likely a death sentence far more severe than the one my parents believed I’d received in that Cleveland Clinic examination room. So, as time passed, my hormone therapy and my intersexuality blended into the backdrop of my life. I played sports, smoked copious amounts of pot, kissed girls and labored through the same, profound fits of heartbreak like everyone else.

And then, too, my music taste became just as chameleonic as my biological sex. Though I listened to presumably heterosexual rock music for much of my childhood, it changed like the weather during my teen years—taking shape in whatever way made sense in the puzzle of my friends’ interests. There were phases of Drake, Nirvana, Bob Dylan, Chief Keef and whatever other various musicians whose songs I could rip from SoundCloud, Grooveshark and YTMP3. You take the good and you take the bad. I have fond memories of sleeping on my neighbor David’s trampoline and listening to Pearl Jam’s cover of “Last Kiss” over and over, only to hop in a kid named Andrew’s Chevy truck the next day and, begrudgingly, listen to Machine Gun Kelly’s debut album (I am from Northeast Ohio, after all).

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-