David Berman’s ghost haunted his music long before August 7th, 2019. He had been there all along, consciously playing host to all of us listeners ever since the DAW first picked up his voice 30 years ago, in that very first breath of Starlite Walker, taken in tandem with then-bandmates Stephen Malkmus and Bob Nastanovich of Pavement fame, just as he did in that very last breath of Purple Mountains’ closing track, the heartbreakingly titled “Maybe I’m The Only One For Me.”

There are few artists whose deaths have impacted me quite like David Berman’s—almost none, really. To be fair, I did grow up with a copy of Actual Air on the bookshelf, “Random Rules” streaming in through the kitchen and “Advice to a Graduate” already mid-verse when I clambered into the passenger seat of my Dad’s car after my final day of high school. I am Berman’s precise target audience: an English major with a concentration in poetry and a penchant for “singers [who] couldn’t sing,” two traits I very much inherited from my Berman-loving, English professor father. But it’s not just my own personal, long-standing attachment to Berman’s work that made his passing so uniquely gutting; it’s the circumstances of his death itself. After years of living as a recluse—and an entire life’s worth of very public mental health struggles—Berman had finally returned to the music scene, albeit under the name Purple Mountains. And, devastatingly, Berman seemed to carry with him a genuine hope for the future, the kind that appeared to perpetually elude him in years prior:

“I feel really optimistic,” he told Uproxx just two months before his suicide. “I feel interested in touring. I feel interested in playing music in a way that I haven’t in the past.” From the conclusion of a July interview with The Ringer, the month before his death: “We finished talking after the label office had closed but before the sun had gone down. David wouldn’t be going out that night. He had songs to re-learn, lyrics to remember, only 39 days until rehearsals. Just more than a month before he will try out this new life to see how it feels. He’s really going to try, to make and honor new connections with people. To do better.” Most heart-rending of all: the day before his suicide, a struggling fan asked Berman if he thought they would ever be happy again. Berman’s response still guts me, even five years later: “I am certain of it. It’s going to be such a surprise.”

Immediately following the news of Berman’s passing, the cult following he had accumulated over the years—the one he remained convinced did not exist—crumbled into collective grief and turned in unison to Purple Mountains, the record he released just a month prior, in a desperate bid for answers. And suddenly, the entire album began to sound eerily prescient and distressingly transparent, permeated as it was by lines like “The end of all wanting / Is all I’ve been wanting;” “Feels like something really wrong has happened / And I confess I’m barely hanging on / All my happiness is gone;” and “Have no doubt about it, hon, the dead will do alright / Go contemplate the evidence and I guarantee you’ll find / The dead know what they’re doing when they leave this world behind.”

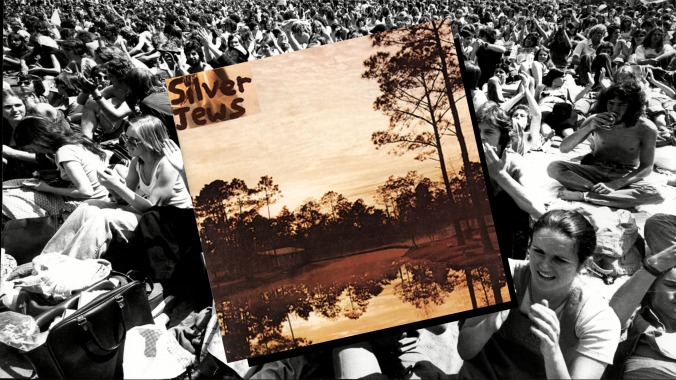

But these threads can be traced much further back in Berman’s discography, all the way to Starlite Walker, the debut studio album released by the Silver Jews (which was, at the time, constantly misrepresented as a Pavement side project, which irked Berman to no end). While Starlite Walker may not be as consistent and cohesive or as polished and ambitious as later Silver Jews hits like The Natural Bridge, American Water, Bright Flight or Tanglewood Numbers, it absolutely stands on its own (especially for a debut), and grows even more impressive with the benefit of hindsight. Every aspect of Berman’s lyrical, musical, and poetic brilliance is right there in embryo, raw and stripped down and still taking shape—and no less brilliant for it. After all, the same ghost lingers in the periphery the entire time, and he’s singing the same tune.

Be it in 1994 or 2019, Starlite Walker or Purple Mountains, David Berman has always been disconcertingly conscious of the eternity he writes himself into with every lyric, every melody—before there was the description of songwriter-as-ghost-host in “Snow is Falling in Manhattan,” there was the welcoming hospitality at the top of Starlite Walker’s “Introduction II,” and later on in the album, the certainty with which he sings “You can’t say that my soul has died away” amid his description of a haunted house in “New Orleans,” a song that eventually unravels into the protracted, frantic repetition of the line “We’re trapped inside the song.”

Trapped in the song as he may be, the Berman of Starlite Walker is at least in good company: Malkmus and Nastanovich are right there with him as his co-hosts, bandmates, college friends and roommates. The origin of Silver Jews was simply the three friends haphazardly recording impromptu jam sessions on their friends’ answering machines in 1989. It’s something out of a movie: After leaving college and getting an apartment together, both Malkmus and Berman got jobs working as art guards at the Whitney, and the conceptual art they were posted in front of provided them with much of their songwriting inspiration at the time (that, and their lunch break acid trips). The band’s first two EPs were the lowest of lo-fi—again, they were literally recorded on answering machines—and often improvised, more a trio of friends playing music together out of sheer love for the craft and each other than anything originally approximating an attempt at a music career.

But then Slanted and Enchanted and Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain happened, and Malkmus and Nastanovich began their journey into the rock music stratosphere—via Pavement, not the Silver Jews. Starlite Walker was released the same year as Crooked Rain, and to hardly a fifth of the buzz—and the buzz it did receive was largely due to the band’s association with Pavement. Due to the obvious connection between the two bands, the indie label Drag City signed Silver Jews but as a result of this otherwise good fortune, Berman spent years watching the Silver Jews be misrepresented as a Pavement “side project” or spin-off.

Despite this misconception, David Berman was inarguably the heart and soul of the Silver Jews, and it was his project more than anything else—and only became more so as time went on and the other two co-founders grew busier with their Pavement responsibilities. But even in Starlite Walker, Berman was the frontman and lead vocalist. Berman composed and wrote every track (save for “Tide to the Oceans,” which he co-wrote with Malkmus). And while Silver Jews does certainly hail from a similar musical lineage as Pavement and the Venn Diagram of fans of both bands is more or less just a circle, Berman carved out his own niche within the indie rock scene, staking firm claim in alt-country territory and propelling it to new heights with the sheer poeticism of his lyrics.

Berman considered himself a poet before a musician; he was always more confident in his words than his voice (even though he himself famously says “all my favorite singers couldn’t sing” on American Water) and even published a phenomenal book of poetry, Actual Air, down the line. These poetic inclinations make themselves immediately known on Starlite Walker: “Trains Across the Sea,” the first song Berman ever wrote (and the second on the record), includes a cheeky reference to Wallace Stevens’ “13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.” “It’s been evening all day long,” Berman croons in that low, dry baritone, a clever wink towards the final stanza of Stevens’ poem which famously begins with “It was evening all afternoon.” But what’s impressive about Berman’s lyricism isn’t his ability to successfully allude to poets, but his inimitable knack for leaning into poeticism while completely avoiding the pitfalls of pretentiousness. “In 27 years / I’ve drank 50,000 beers,” he sings at the song’s end. “And they just wash against me / Like the sea into a pier.” The instrumentation is simple, just two chords back and forth accompanied by a light drumline, letting Berman’s voice become the song’s focus as he asks, at once wistful and world-weary, “Half hours on Earth / What are they worth? / I don’t know.”

Similarly, “Advice to the Graduate” features Berman at the height of lyrical prowess, the titular advice constantly oscillating between (or, often, simultaneously being both) laughably strange and disarmingly heartfelt: “Sleep on your back and ash in your shoes / And always use the old sense of the words / Your third drink will leave you astray / Wandering down the backstreets of the world.” It’s another standout track on the record, and I’m not just saying that because it pulls at something in my chest whenever it comes on, like some Pavlovian response to hearing my Dad lovingly play it for me on repeat when I first graduated. With guest vocals from Malkmus and infinitely memorable lines like “On the last day of your life, don’t forget to die,” “Advice to the Graduate” is a rightful Silver Jews all-timer. Something about the soar of the chorus always hits me where I live, the pitch of “Well, I know you got a lot of hope for the new men” inexplicably tightening my throat every time.

While “Trains” and “Advice” are given their rightful due by critics and fans alike, they’re far from the only phenomenal tracks on Starlite Walker; I’d make a case for the underrated “Living Waters” and, especially, “New Orleans” as well. “Living Waters” feels a lot like later Silver Jews—although perhaps that internal association stems from the similarity of the track name to American Water and the similarity of the lyrics (focused around the word “people”) to “People” off of that album—and is effortlessly charming in its simplicity. It is, at least in my experience, the most pervasive earworm of Starlite Walker, with even the opening lines (“Now people are good and people are bad / And I’m never sure which one I am”) getting stuck in my head for hours at a time. And that’s not even mentioning the whistling sections. It’s just good ole alt-country twang—see: the diphthong Berman’s twang inserts into the beginning of the word “imitation”—and one of the “jammiest” tracks on the album, making it easy to remember how the band started out.

Then there’s “New Orleans,” which contains some of my favorite lyrics off the entire record. It’s a masterclass in rapidly switching between utter devastation and dry, ridiculous wit; Berman goes from howling the plea “Please don’t say that my soul has died away” directly to informing listeners that “There is a house in New Orleans / Not the one you’ve heard about, I’m talking about another house.” It is also, of course, the site of the phenomenal buildup to breakdown at the song’s end: the repetition of “We’re trapped inside the song / Trapped inside the song / Trapped inside the song / Where the nights are so long” eventually gives way to “There’s traps inside us all / … / And the night is so tall / And the knife is so tall,” the fervor in Berman’s voice steadily increasing as the track reaches its peak. It also boasts an absolutely gorgeous opening to boot: the soft croon of “I’m scared (I swear) of you / In the tunnel, in the darkness, the darkest walls of blue / There’s beasts and there’s men / And there’s something on this Earth that comes back again.”

There are, however, some weaker songs on the album; some of Starlite Walker, like most debuts, is spent throwing shit at the wall to see what sticks. ”Tide to the Oceans,” while punny and pretty, is less memorable than most. The discordant, experimental spoken track “The Country Diary of a Subway Conductor” is inarguably the least accessible track on the record, sounding less like a song in the classic sense and more like you left a bunch of tone-deaf sixth graders in the band classroom unattended, while a cowboy incomprehensibly monologues over the din. It’s a strange track, so I understand why it doesn’t top most people’s lists—and while it doesn’t quite top mine either, I am a known lover of the goddamn strange, so I’m always quite tickled by it. “Pan American Blues” falls in a similar camp, in that it’s also a bit strange, from the baffling lyrics (“A fifth on decoration day for the doctor that fixed my arm / The federales back in Tucson, each one got an arm gone” or “Can you tell the answer from the ants? / History’s got its walking papers”) to the dissonant piano plunking faintly in the background to the particularly odd delivery of “Well, it ssssseeems like a freeze-out!” But, again, I personally do like it quite a bit—it feels a little proto-Modest Mouse, somehow.

“Rebel Jew” leans hard into the country side of Silver Jews’ alt-country get-up, and has, possibly, the weakest vocals on the album (made starker by the incredibly sparse instrumentation); it does, though, have some excellent lines: the track begins with “In the times I dream of Jesus / It’s like he’s coming through the walls / When I’m working at my desk at night / I hear his footsteps in the hall,” and the second chorus repeats “She is a rebel state / And it’s not too late for her to break,” which I’ve always enjoyed. So even while some of the shit thrown doesn’t quite hit the target, I’d argue almost all of it does stick, to some extent—although perhaps that’s more a matter of individual taste.

But while Berman is most comfortable in his native home of the written word, that doesn’t mean he sidesteps instrumentation entirely. In fact, he’s fond of instrumental tracks, with at least one peppered throughout every album, beginning with Starlite Walker’s third song,“The Moon is the Number 18.” (According to Berman himself, the instrumental tracks are apparently included for the primary purpose of serving “as respite from the words and/or my voice, which doesn’t agree with everyone, to say the least.”) “The Moon” groans feedback into the listener’s ear before shifting into a grungy rhythm, and overall feels more like the band enjoying jamming out with each other than anything else. That is, after all, where they got their start.

The album closer, “The Silver Pageant,” is also an instrumental, although it begins and ends with the rapid, pleasant chatter of a crowd. The song feels a little like standing in a bar with your friends as you try to hear each other over the band in the corner (at one point, a male voice breaks into a chant of “Search party!!!” and everyone cheers). Largely guitar-focused but with occasional interludes of dissonant piano that sounds a little like if you played “Chopsticks” with all the wrong notes, “The Silver Pageant” ends up feeling like an unexpectedly poignant send-off to the record. At the end, when the music fades out, the last words you can make out are a faint voice calling out, “Alright, thanks for coming, man”—the hospitable goodbye to “Introduction II”’s hospitable welcome. Say what you will about David Berman, but that man knows how to host. To haunt. They’re one and the same, really.

Berman lived inside of contradictions, simultaneously desperate to be remembered and utterly terrified by the prospect. In that same June 2019 Uproxx interview, he argues that it’s scarier to be remembered than to be forgotten—because, then, “you’re frozen. And it’s scary to see people frozen at their peak or reaching their peak.” But for some reason he keeps trapping himself in those songs anyways, welcoming us in with warmth and waving goodbye like he’s glad we came. “My friends,” Berman sings at the very end of “Introduction II,” his voice intertwining with Malkmus as they breathe out the words at a slightly asynchronous pace. “Don’t you know that I never / Want this moment to end?” A beat. A scratchy strum of the guitar. Their voices pick up again, actually in unison for the first time in the entire song, going soft at the end with a bittersweet wist: “And then it ends.”

Purple Mountains is devastating to listen to, especially given what followed so soon after it was released. But so is Starlite Walker, all the more so because of how disconcertingly similar the devastation is, and how much earlier in Berman’s life it came about. We watch, helpless, as the fully self-aware specter of a once-David-Berman ushers us kindly into the sitting room of his own mind, tells us to make ourselves comfortable. He is trapped as a gracious host inside his own song for all eternity. Except, the song doesn’t last an eternity, not for us listeners. It lasts roughly three minutes. So eternity winds to a close and the final chords play. He waves goodbye (always gracious), keeps stoking the fire, keeps singing his lines. And then it ends.