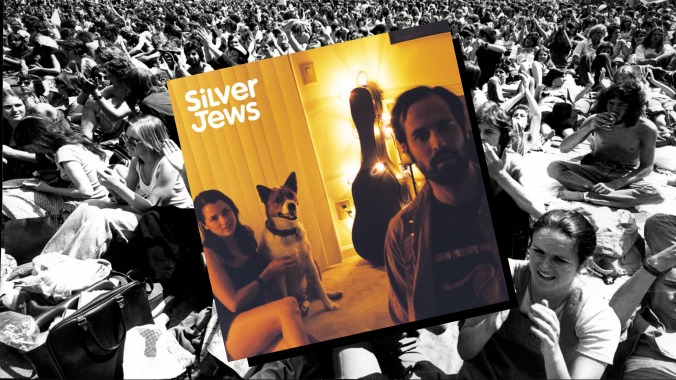

Time Capsule: Silver Jews, Tennessee

Every Saturday, Paste will be revisiting albums that came out before the magazine was founded in July 2002 and assessing its current cultural relevance. This week, we’re looking at the companion EP to Silver Jews’ fourth studio album, a collection of four tracks about the fruits of domesticity, fixing horse races, bedding librarians, hating your family and making your own luck.

In 1998, Silver Jews made one of the greatest albums of all time, American Water. Songs like “Smith & Jones Forever,” “Random Rules” and “The Wild Kindness” remain emblematic in indie rock’s canon—and they remain emblematic of David Berman’s talents as a songwriter (“bluebirds lodged in an evergreen altar” still lingers in my dreams). The American Water Band—Berman, Stephen Malkmus, Mike Fellows, Tim Barnes and Chris Stroffolino—sounded tighter than ever then, but Malkmus and Stroffolino wouldn’t return for the next Silver Jews LP, Bright Flight, in 2001. Malkmus had to go and make the last Pavement album, Terror Twilight, and put out his eponymous debut solo record in the time between.

Bright Flight is a good record, but it’s not as good as American Water. Truth be told, few records are as good as American Water. But it’s the album that introduces a new voice into the Silver Jews universe: Cassie Berman, David’s wife. I am somewhat of a romantic when it comes to the collaborations between the Berman spouses. To make Bright Flight, they moved to Nashville and drank in the city’s country scene. Malkmus’s absence could be felt, as Bright Flight was the first Silver Jews album that sounded like a David Berman solo album. And that was okay! “When God was young, he made the wind and the sun,” he sang. “Since then, it’s been a slow education.” It’s a staggering introduction to a wistful erudite’s linguistic playground. Having Cassie appear on songs like “Slow Education,” “Let’s Not and Say We Did” and “Tennessee” made Bright Flight sound like the lo-fi indie version of a Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris record.

“Tennessee” was a particular standout on Bright Flight. A four-minute song that pauses midway through as if beginning a new story, it was such a profound, shaking track that Berman elected to name an EP after it. The song is meta and familiar, as Berman riffs on his and Cassie’s move to Nashville, talking about living in “Nashville and I’ll make a career out of writing sad songs and gettin’ paid by the tear.” He gets cute in the chorus. “Marry me and leave Kentucky,” Berman goes. “Come to Tennessee, ‘cause you’re the only 10 I see.” When Berman repeats the “you’re the only 10 I see” bar, the track kicks into gear through Paul Niehaus’s pedal steel guitar. Cue Cassie’s unmistakable doubling voice in the post-chorus: “I’ve looked through offices and honky-tonks for men man enough to be Mister, Misses Tennessee.” A love song, “Tennessee” is not without Berman’s commonplace phrasings: “Punk rock died when the first kid said ‘Punk’s not dead,’” he tackles on verse three; “We’re off to the land of club soda unbridled, we’re off to the land of hot middle-aged women; off to the land whose blood runneth orange” goes the fourth verse. All Vols references and age preferences aside, Tennessee’s namesake is some of Berman’s prettiest work.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-