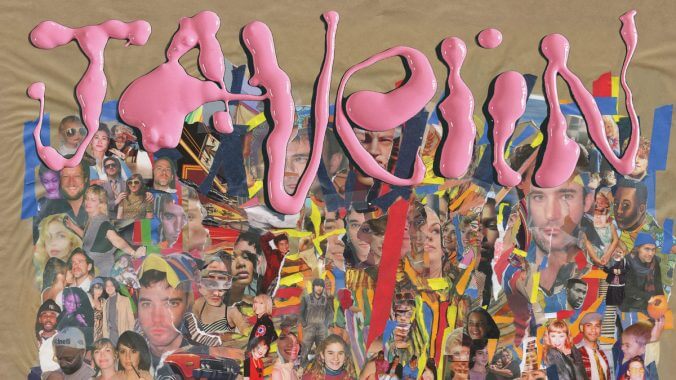

Album of the Week | Sufjan Stevens: Javelin

The Detroit indie hero returns to singer/songwriter mode for magnificent, riveting and gorgeous songs of sacrifice

Sufjan Stevens simply does not stop. The man is always doing something, whether it be making a concept record about a planetary system, writing songs for movies, adapting his album to a stage production or making countless instrumental epics. Rarely does he treat us with a proper studio record in the vein of something like 2004’s Seven Swans or 2005’s Illinois. But, just three years after his last record—the sprawling and opulent The Ascension—he’s back. Billed as a spiritual successor to Carrie & Lowell but with a focus on ’70s LA studio wizardry, Javelin sees the Detroit-born songwriter return with a piano and acoustic guitar in tow.

Although the album’s promotional cycle would have you believe Javelin is a straightforward extension of the gentle melancholy of Carrie & Lowell, that’s a slight misnomer. Rather, Stevens’ latest blends the synth-driven freakouts of 2010’s The Age of Adz with his quieter endeavors. Take the opening track “Goodbye Evergreen,” which makes the album’s thesis clear from the outset. Soft piano chords accompany Stevens’ diaphanous vocals, and he’s soon joined by background singers Megan Lui and Hannah Cohen—who harmonize with him to craft a rich, sumptuous arrangement. Whereas these first few moments are the sonic equivalent of a gilded Victorian mirror, Stevens shatters that mirror just a minute into the song; industrial clanks and clinks usher in a blast of unexpected pandemonium. Imagine The Age of Adz chapters “Futile Devices” and “Too Much” cut apart and pasted back together.

This amalgamation of filigreed string instruments and hammering electronics continues on “Everything That Rises,” which could be a Seven Swans track replete with its calls to Jesus, save for the mechanized percussion that drives Stevens forward. On a traditional singer/songwriter album from the indie-rock savant, drums are absent—letting Stevens dictate his own tempo and pacing. Here, there’s an air of urgency pushing him to his resolutions, like the exit music that swells when an award-winner starts taking up too much airtime. Javelin’s insistent percussion enters about halfway into a song, slowly rising in volume, forcing Stevens to raise his voice to cut through the clatter of his own creation.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-