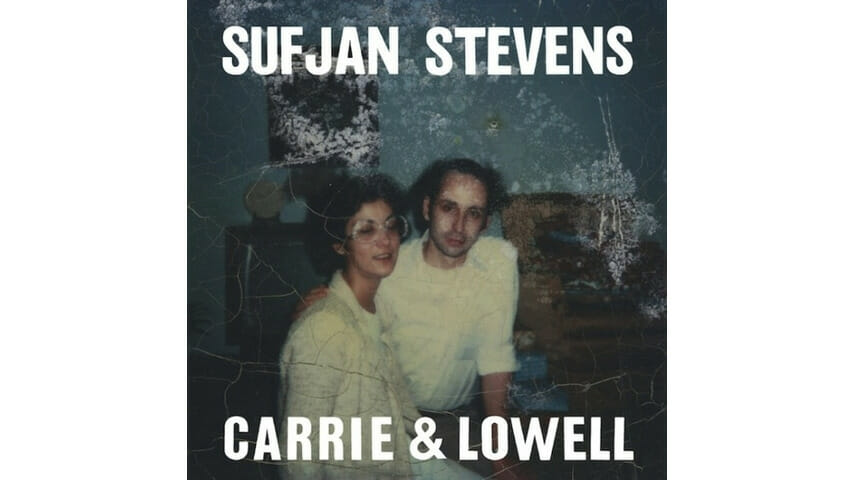

Sufjan Stevens: Carrie & Lowell

Sufjan Stevens’ Carrie & Lowell is a hyper-specific recount of memories from Stevens’ childhood, and of the emotions that struck him following the death of his mother, whom he barely knew. And while the actual facts that the album is based on seem like they could provide a wealth of fertile ground to cultivate great art—and they do—there is also the possibility that the events could be too personal for listeners to relate to or to gain something of an understanding to apply to our own life.

But that’s the thing about family: everyone has one. Everybody comes from somewhere, and no matter how perfect your situation—how loving your mother or father, how ideal your childhood—ideas of longing and loss and a desire to understand events that you might have been too young to fully grasp at the time are ever-present.

Making sense of life’s misfortunes is not new to Stevens. Previously on Age of Adz he went glitchy electronic after growing tired of his voice, the banjo and the trumpet, in a need to exercise demons of heartbreak, depression and physical illness. But it is fitting that he returns to simplicity to tell the story of his childhood, as the music retreats to Stevens’ most bare and minimal. It is almost a devolution of all he has learned as a composer to get back to his most basic of themes: the desire to be loved and our own mortality. On “Blue Bucket of Gold,” he requests “Tell me you want me in your life, or raise your red flag, just as I want you in my life.” His wishes are plain, his needs not convoluted in the least.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-