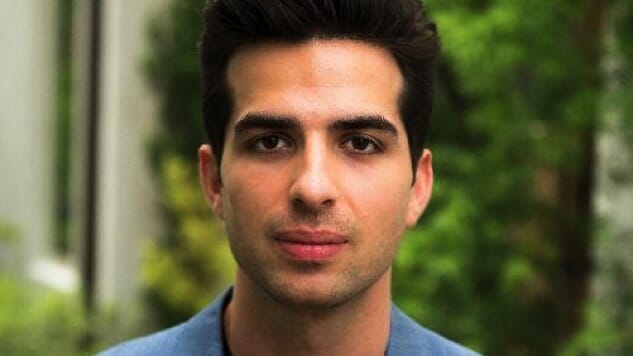

Kor Adana is Mr. Robot’s Mr. Robot

What It’s Like to Be the Tech Consultant on TV’s Most Tech-Friendly Series

Kor Adana has the kind of job both aspiring and seasoned writers alike would kill for. Namely, as a recently promoted staff writer, he’s one of a handful of individuals currently helping to dictate the creative course of Mr. Robot, USA’s brand-shattering, breakthrough series and one of television’s newly minted must-see dramas.

For the uninitiated, the show follows the exploits of Elliot Alderson (Rami Malek), a young hacker and drug addict who comes under the mentorship of Mr. Robot (Christian Slater), the mysterious, yet charismatic leader of an Anonymous-style group called fsociety. The organization’s brand of anarchy-infused hacktivism hinges on cleansing the world economy by bringing down its evil corporate influences, as personified by a not-so-subtle Enron stand-in, E Corp (aka “Evil Corp”). The show’s haunting, often surreal, dive into Elliot’s damaged psyche and the world of hacking—a subculture previously characterized by Hollywood as everything from squirrelly sleazeballs, to archetypal punk rockers with laptops—quickly earned critical raves, a fervent fan following and a bevy of awards (most notably a Golden Globe for Best Drama Series and an additional Best Supporting Actor trophy for Slater).

Elliot is a character all too familiar to Adana, who dabbled in hacking during his formative teen years. It was this very background that encouraged Mr. Robot creator/showrunner Sam Esmail to bring him onboard as his assistant and just as quickly promote him to a technical advisor position.

“Honestly my role doesn’t really exist on other shows,” Adana freely admits during our interview. Indeed, this level of authority and influence when it comes to developing the technical vocabulary of Mr. Robot crystallizes the many ways in which the series distinguishes itself from its more traditional cable peers. Besides offering complex characters, shocking twists and unnerving visual imagery, the series has been embraced by the tech community for displaying a grounded approach to hacking that puts all other Hollywood productions to shame. Much of this can be traced to Adana, who can spend upwards of several weeks coordinating with the prop, set decoration and video/animation departments in assuring that what appears on screen—no matter how brief—is technically sound.

“I write down these detailed breakdowns of how each hacking screen behaves and how it operates,” he explains. “Sometimes I’ll do the hack myself and do a screen recording or I’ll find footage of the hack being done. Then, it’s a battle with the legal department about clearing the right pieces of software or hardware. I come from a place of wanting everything to be as authentic as possible. So if you can do this hack for real—which you should be able to, because that’s what we set out to do in the writing phase—I want to use the tools you’d actually use, I want the hardware you’d actually use and I want to show that on the show.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-