True Detective: “Maybe Tomorrow”

Episode 2.03

Last night, as I watched “Maybe Tomorrow” for the second time—the first came when it was released on HBO’s preview app weeks ago—I was struck again by the power of the opening scene. And because I’m just as entrenched in the world of instant reaction as anybody else, I took to Twitter to write a note, since deleted, about how unfortunate it was that the rest of the episode suffered after such a strong start. That’s what I remembered about the ensuing 53 minutes—an underwhelming installment complete with an erratic plot, rampant cynicism and a convoluted message. In fact, that’s exactly what I said when anybody asked for my early take on the new season (reviewers were shown the first three episodes): The third episode will really let you down.

And then I watched those 53 minutes again, and saw something completely new. It felt like great television, with details and connections I’d missed the first time around, and a far more cohesive story imbued, at times, with great impact. Even the darkness that had weighed on me the first time around now seemed meaningful, and a somber kind of intelligence had replaced the vague sense that I was watching a cliche.

Now I’m a bit befuddled, and I can’t remember a show making me feel this way before. It’s a far cry from the rapturous experience of season one, but I’m slowly warming up to the idea that we’re witnessing a new kind of excellence. Even in the golden age of television, where difficult shows are allowed to flourish, I don’t know that I’ve ever come across a show whose reason for being wasn’t apparent by the third episode. Here, we might have that rare animal—a work so thematically difficult, and so committed to a strange worldview, that it requires a new kind of participation from the viewer. It would be ridiculous to compare it to a book like Ulysses, since this is still television and True Detective is still fun to watch, but maybe our usual levels of immersion aren’t adequate here. And maybe there is a rich experience waiting for those who can bring the kind of intense focus that season one pulled from us in an almost involuntary way. It’s not quite as beckoning as the world of Cohle and Hart—Pizzolatto is adamantly unafraid of playing hard-to-get this time around—but the rewards might not be as diminished as they felt on first viewing. They might not be diminished at all.

![]()

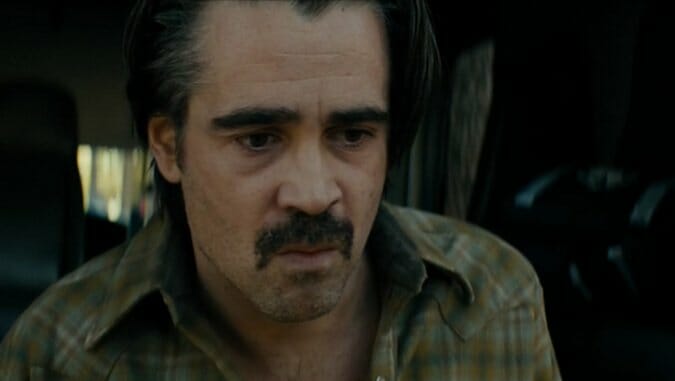

Let’s return to that first scene: A man—a garish sort of Johnny Cash/Elvis knock-off—spotlit in a dark, empty bar, crooning (read: lip-synching) Conway Twitty’s version of “The Rose” in a classic baritone, gyrating and emoting and milking every ounce of melodrama from the words. Meanwhile, in a booth to the side, Ray Velcoro sits across from his father, confused. They are in a type of purgatory, but that label would be too simple—just like it will be too simple when everyone compares this scene to Twin Peaks, or any other work by David Lynch. I don’t deny the influence, but unlike Lynchian productions, which drip with insincerity and an eerie misanthropy, there is something very earnest at work here, and it’s more than just the dream-like near-death ravings of a detective who—to everyone’s great relief—is not actually dead.

And in fact, this is an important point—not only is Ray Velcoro not dead, but that other adjective I just used, “near-death,” doesn’t apply either. In fact, he was just stunned by riot shells, and though he sustained a few cracked ribs, it wasn’t anything close to fatal. So we can forget purgatory—that’s not what Ray was experiencing in his dreams. We need to look closer, and listen to the conversation:

Father: You step out the trees…you ain’t that fast…ah, son, they kill you. They shoot you to pieces.

Son: Where is this?

Father: I don’t know. You were here first.

There is no such thing as “just a dream” in Pizzolatto’s world, and though it’s tempting to believe that Velcoro’s dream-state has gone through a sort of reality-fusion, seeing as how “The Rose” is also playing on the radio when he wakes up, the real lesson of this scene comes in a bit of philosophy we learned in season one: Time is a flat circle.

What Ray saw, in that bar, was like a premonition. The word doesn’t quite fit, though, because that prefix, “pre,” implies a sort of chronology, and what we witnessed in his interaction with his father was an example of Pizzolatto’s conception of time—it all happens at once. So what’s the true meaning of this meeting? Simple: Ray’s father is showing him how he dies—a flight through trees, a hailstorm of bullets. The place where they sit is somewhere you go after death, but Ray’s father is still alive, and that last line delivers an important message: Ray died first, and was waiting there, in that empty bar, when the father arrived.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-