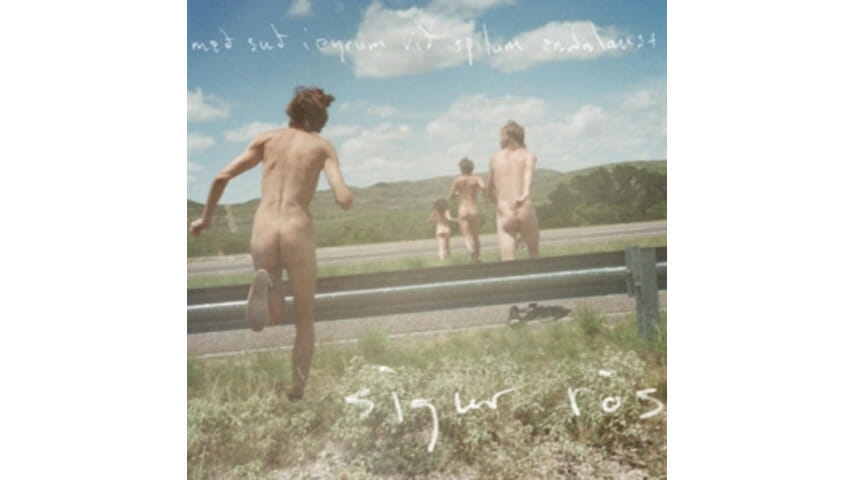

Sigur Rós: Með suð í eyrum við spilum endalaust

Icelandic post-rockers find fresh perspective on revelatory record

I once got drunk at Björk’s house and did a little jig with her garden gnome beneath the green ribbony glow of the Northern Lights. I danced on the bar at the now defunct Reykjavík all-hours bar Sirkus, and sang George Harrison’s “Got My Mind Set On You” with a beautiful blonde ice queen. I climbed a glacier and stood tippy-toe on a grey mountain of moss to glimpse the stone building where Vikings first colonized the island nation in the 9th Century.

But all I really wanted to do when I went to Iceland was see the swimming pool. Not just any swimming pool, mind you. This one had magical powers—or so it seemed. Because it was in this refurbished public watering hole that Sigur Rós had birthed some of the most otherworldly sounds to ever be labeled “indie rock.” So I hopped in my friend’s car and pointed it north, ignoring my throbbing bladder until I reached a tiny outpost called Álafoss. There, in a building not much more stately than a shack, I found the place, now called Sundlaugin studio.

I cupped my hand to the window, repeatedly fogging it with my breath, taking in the antiquated Neve console, the banks of discarded guitars and the cellos propped against one wall like hunks of an asteroid spit up by the galaxy. When I finally gave in to my urge to pee, I couldn’t bring myself to sully Sundlaugin’s perimeter. Instead, I hiked to a nearby stream. It seemed so much more respectful.

Ever since 1999 when their second album, Ágætis Byrjun, spread like a handshake drug among gob-smacked tastemakers, Sigur Rós has carved out a rather impossible legend. Looking back, it’s amazing how much it stood out in a year crowded with milestones: Magnetic Fields’ 69 Love Songs, The Flaming Lips’ prog-pop reinvention The Soft Bulletin, the percocet twang of Wilco’s Summerteeth, and Pavement’s swan song Terror Twilight.

Somehow—amid all those landmarks—it was a blue cardboard sleeve with a silver alien baby on the cover that made the most curious impact. Intricately enunciated words nobody could understand. A polysexual angel singing and moaning as he dragged his bow mournfully across the guitar. Loud/soft/loud dynamics that took then-rote rock ’n’ roll expression to a state of near constant orgasm. It didn’t sound human. Hell, it didn’t even sound earthly.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-