The 100 Best Horror Movies of All Time

This list has been a long time coming for Paste. We are fortunate—some would say “cool enough”—to have quite a lot of genre expertise to call upon when it comes to horror movies in particular. Case in point: We have so many writers focused on horror that we’ve produced huge lists of the best horror films on Netflix, Amazon Prime and Hulu that are all updated on a monthly basis. We’ve even given you the likes of the 50 best zombie movies of all time, the 50 best slasher movies of all time, and the 100 best vampire movies of all time, if you can believe that.

But we also clearly need a true “master list,” one that can include entries from any and all subgenres. And so, we give you the following: A practical, must-see guide through the history of the horror genre.

There are classic films on this list, of course. There are also likely a handful of independent features that will be unknown to all but the most dedicated horror hounds. There are foreign films from around the globe, entries that range from 1922 to 2023. In some cases, you will likely be shocked by films that are missing. In others, you’ll find yourself surprised to see us going to bat for films that don’t deserve the derision they’ve received.

One thing is for certain: With all the films that were nominated, we could easily have made this list 200 entries long. Horror cinema speaks toward the dark side in all of us, allowing us to confront the most frightening, primal forces we struggle with every day—death, and human malevolence—in a way that is actually constructive in strengthening the psyche. In the oddest of ways, horror movies help us overcome our own fears.

Here are the 100 best horror movies of all time:

100. The Blair Witch Project, 1999Directors: Eduardo Sánchez, Daniel Myrick

Where Scream reinvented a genre by pulling the shades back to reveal the inner workings of horror, The Blair Witch Project went the opposite route by crafting a new style of presentation and especially promotion. Sure, people had already been doing found footage movies; just look at The Last Broadcast a year earlier. But this was the first to get a wide, theatrical release, and distributor Artisan Entertainment masterfully capitalized on the lack of information available on the film to execute a mysterious online advertising campaign in the blossoming days of the Internet age. Otherwise reasonable human beings seriously went into The Blair Witch Project believing that what they were seeing might be real, and the grainy, home movie aesthetic captured an innate terror of reality and “real people” that had not been seen in the horror genre before. It was also proof positive that a well-executed micro-budget indie film could become a massive box office success. So in that sense, The Blair Witch Project reinvented two different genres at the same time. —Jim Vorel

99. Häxan, or Witchcraft Through the Ages, 1922Director: Benjamin Christensen

A truly unique silent film, Häxan is presented as a historical documentary and warning against hysteria, but in function it plays much more like a true horror film, especially considering the timeframe when it arrived in Danish and Swedish cinemas. Director Christensen based his depictions of witch trials on the real-life horrors codified in the Malleus Maleficarum, the 15th century “hammer of witches” used by clergy and inquisitors to persecute women and people with mental illness. The dreamlike—make that nightmarish—dramatization of these torture sequences were almost unthinkably extreme for the time, leading to the film being banned in the U.S. But put simply: There’s iconography in Häxan that grabs hold of you. Puffy-cheeked devils with long tongues lolling lazily out of their mouths. Naked men and women crawling and cavorting in circles of demons, lining up to literally kiss demonic asses. Scenes of torture straight out of Albrecht Dürer woodcuts or Divine Comedy illustrations. The grainy silence of black and white only makes Häxan more otherworldly to watch today—it feels like some kind of bleak Satanic relic that humankind was never supposed to witness. This is one silent film you won’t want on with children in the room. —Jim Vorel

98. The Conjuring, 2013Director: James Wan

Let it be known: James Wan is, in any fair estimation, an above average director of horror films at the very least. The progenitor of big money series such as Saw and Insidious has a knack for crafting populist horror that still carries a streak of his own artistic identity, a Spielbergian gift for what speaks to the multiplex audience without entirely sacrificing characterization. Several of his films sit just outside the top 100, if this list were ever to be expanded, but The Conjuring can’t be denied as the Wan representative because it is far and away the scariest of all his feature films. Reminding one of the experience of first seeing Paranormal Activity in a crowded multiplex, The Conjuring has a way of subverting when and where you expect the scares to arrive. Its haunted house/possession story is nothing you haven’t seen before, but few films in this oeuvre in recent years have had half the stylishness that Wan imparts on an old, creaking farmstead in Rhode Island. The film toys with audience’s expectations by throwing big scares at you without standard Hollywood Jump Scare build-ups, simultaneously evoking classic golden age ghost stories such as Robert Wise’s The Haunting. Its intensity, effects work and unrelenting nature set it several tiers above the PG-13 horror against which it was primarily competing. It’s interesting to note that The Conjuring actually did receive an “R” rating despite a lack of overt “violence,” gore or sexuality. It was simply too frightening to deny, and that is worthy of respect. —Jim Vorel

97. The Burning, 1981Director: Tony Maylam

If Halloween codified many of the slasher conventions in 1978, then Friday the 13th opened the floodgates wide with its unexpected success and profitability in 1980. A slew of imitators and low-rent slashers poured into drive-ins and grindhouses in the decade that followed, but The Burning is one of the few to rise above the scrum. At first it seems just like one of the pale Friday the 13th imitators, aping the summer camp setting much in the same way as Sleepaway Camp would later do, but there’s an artistry and shocking quality to the violence and gore here that isn’t present in most of the copycats, which were more interested in titillation rather than genuine surprise. Drawing upon the New York urban legend/campfire story of “Cropsey,” which tells of a disfigured camp counselor returned from a presumed grave to seek vengeance on counselors, The Burning takes its time and lures the audience into a rather effective false sense of security through establishing a lighthearted tone and scenes of counselors scaring each other. That status quo is eventually shattered in one of the more amazing early-’80s scenes of slasher carnage, which occurs when Cropsey (Lou David) ambushes an entire raft full of counselors and campers and systematically dispatches them in the most grisly format imaginable. It must have had audience members excusing themselves to flee the theater at the time. —Jim Vorel

96. They Look Like People, 2015Director: Perry Blackshear

I fully expect there to be someone reading this—one of the few people who has actually seen this film—arguing that it doesn’t belong on a “horror” list, but they would be mistaken. And it’s true, They Look Like People is genuinely far creepier than many other, more traditional horror films on this list that aim to entertain more than legitimately scare. What we have here is a very unusual, unflinching portrait of mental and emotional illnesses that spin wildly out of control. It would be really easy for the story to be more conventional—guy’s friend visits, turns out the friend is crazy—but They Look Like People messes with the audience’s expectations by giving both of the male leads (MacLeod Andrews and Evan Dumouchel) their own mental hurdles to overcome. They never react quite like we expect them to, because neither sees the world in a healthy way. It’s a film where the threat and implication of terrible violence, evoked via constantly on-edge atmosphere, becomes almost unbearable—whether or not it actually arrives. Thanks to some very, very strong performances, you always feel balanced on the edge of a knife. Deliberately paced but thankfully brisk (only 80 minutes), They Look Like People leaves much unanswered, but we still feel satisfied anyway. It’s one of the most brilliant and overlooked of modern horror films. —Jim Vorel

95. In Fabric, 2019Director: Peter Strickland

Peter Strickland is a cinematic aesthete, an artist who is both beguiled by and displays a mastery over the slightest and most ephemeral elements of production design, visuals, texture and sound in his films. In 2012’s Berberian Sound Studio, he first applied this degree of hyper-attention toward the psychological horror genre, setting his story within the world of film industry foley itself to provoke audience reflection on sound and the nature of reality. In 2019’s In Fabric, meanwhile, he once again returns to core influences that range from Italian giallo to 1970s European erotic thrillers, but suffuses them with a gauzy style that is all his own. His films are sumptuous experiences that stimulate every sense one can use to appreciate cinema.

In Fabric is one of those films where the premise could just as easily be applied toward a five-minute horror short as it could a feature film. You can say it in a couple words: “A haunted dress ruins people’s lives.” That sounds like source material easy to envision within the context of a cheesy horror anthology, like something from England’s Amicus Productions in the 1970s, but in Strickland’s hands it becomes the basis for a phantasmagorical descent into a certain, lushly appointed style of madness. In Strickland’s world, you’d end up stark raving mad in a room with padded walls, but they’d feel amazing to the touch. In Fabric deserves far more attention that it received last year.

94. Sator, 2021Director: Jordan Graham

There’s something in the forest. But at the same time, there’s nothing much at all. A man, a cabin and maybe—maybe—something more. Sator, a mumblecore horror somewhere between a modern-day The Witch, The Blair Witch Project and Lovecraft, is a striking second feature from Jordan Graham. It’s the kind of horror that trades jump scares for negative space, one that opens with imagery your typical A24 beast saves for its finale. Sator’s dedication to its own nuanced premise, location and tense pace makes it the rare horror that’s so aesthetically well-realized you feel like you could crawl inside and live there—if it wasn’t so goddamn scary. Sator is a name, an evocation, an entity. He’s first described, by Nani (the late June Peterson, excellent), as a guardian. Nani’s known Sator (whatever he may be) for a long time. The film represents shifts in time, and the physical transportation to places soaked in memories, with an aspect ratio change and a black-and-white palette. Nani’s lovely longhand script is practiced well from a lifetime of automatic writing, with the words—including some of the opening company credits, which is a great little joke—pouring from her pen and claiming a headwater not of this world. That same paranormal river flows to her grandson Adam (Gabriel Nicholson), that aforementioned man in the woods, whose relationship with the voices in his head is a bit less comfortable. It’s a stark, bold, even compassionate film—which offers imperfectly planted details of a battered and bruised family at its core—with plenty to comprehend (or at least theorize about) for those brave enough to venture back into the forest for a rewatch. As scary as it is, Sator is an experience with enough layers and craftsmanship that its alluring call will rattle in your head long after you’ve turned it off.—Jacob Oller

93. Paranormal Activity, 2007Director: Oren Peli

Here’s a statement: Paranormal Activity is the most wrongly derided horror film of the last decade, especially by horror buffs. That’s what happens in the wake of massive overnight success, and immediately derivative, inferior sequels: The original gets dragged down by its progeny. The original Paranormal Activity is a masterful piece of budget filmmaking. For $15,000, Oren Peli made what is probably the most effective “for the price” horror movie ever released, surpassing The Blair Witch in terms of both tension and narrative while pulling off incredibly unnerving minimalist effects. Yes, there are some stupid, “I’m in a horror movie” choices by the characters, and yes, Micah Sloat’s “get out here so I can punch you, demon!” attitude is irritating, but it’s calculated to be that way. Sloat is a reflection of the toxic “man of the house” attitude, a guy who would rather be terrorized than accept outside help. Meanwhile, Katie Featherston’s realistic performance as a young woman slowly unraveling is a thing of beauty. But beyond performances, or effects, Paranormal Activity is a brilliant case study in slowly building tension, and in raising an audience’s blood pressure. I know: I saw this film in theaters when it was still in limited release, and I can honestly say I’ve never been in a movie theater audience that was more terrified. How can I tell? Because they were so loud in the moments of calm before each scare (the most dead giveaway of all: when a young man turns to his friends to assure them how not-nervous he is). This was just such an event—there were actually ushers standing at the entrance ramps throughout the entire film, just watching the audience watch the movie. I’ve yet to ever see that happen again. Deride all you want, but Paranormal Activity scared the hell out of us. —Jim Vorel

92. When Evil Lurks, 2023Director: Demián Rugna

Director Demián Rugna’s debut horror feature Terrified has slowly but surely captured the attention of horror geeks around the world, but 2023’s When Evil Lurks is likely to complete his ascent to a star in the genre, even if he hasn’t yet produced an English-language feature. This is one of the most disturbingly creative and fraught possession horror films to arrive in decades, dropping the viewer absolutely cold into a setting where god is dead and evil is seemingly running roughshod over the Earth.

It’s deeply disconcerting to watch a horror film centered around demonic possession where the act of possession isn’t decried by the characters as some foolish impossibility, but is instead a well-understood facet of daily existence in this world. The arrival of a “rotten one” in a community is like the outbreak of an exotic and extremely deadly disease, requiring the presence of a specifically trained “cleaner” to dispose of the gestating demon in a way that doesn’t result in the entire area quickly becoming infected with evil. What happens when regular people have to deal with that kind of horror themselves? We quickly come to realize that there are a plethora of “rules” to surviving these encounters, but Rugna doesn’t handhold the audience and inform us of what they all are–every interaction instead becomes a paranoid question of wondering if the characters have become possessed, or vulnerable to attack. Never are we certain of what is true, and what is folklore. Pair this uncertainty with unflinching savagery and brutality, and you have one of the most gut-wrenching horror films to make its way to a small number of U.S. theaters in recent memory. —Jim Vorel

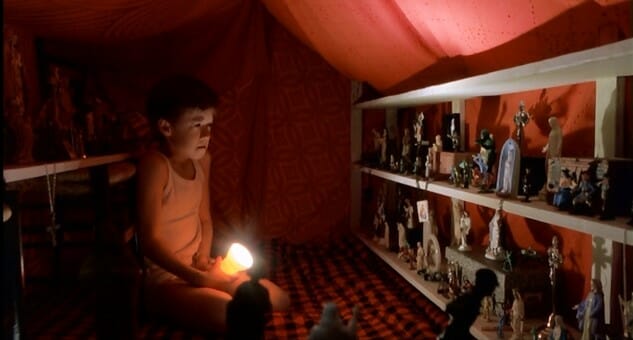

91. Creepshow, 1982Director: George A. Romero

The anthology is a film structure that has always been native to horror—it captures the campfire “spooky stories” aesthetic and often allows promising young directors a platform on which they can shoot what are essentially short films to launch their careers. On the flip side, however, anthologies rarely end up in “best film” discussions because every contemporary appraisal of any given anthology is always quick to highlight the exact same point: They are uneven in quality by their very nature. Creepshow, however, has an advantage here: It maintains a thematic and visual consistency because Romero directed all of the segments himself. Working with Stephen King in his screenwriting (and unfortunately, acting) debut, Romero dives deep into a childhood obsession and love for EC Comics horror series such as Tales From the Crypt and Vault of Horror, using vibrant, phantasmagorical splashes of color in reaction shots in a way that almost parallels how Sam Raimi would eventually evoke comic book panels in Spiderman 2. The stories themselves are wonderful, pulpy fun, from the gothic, ghostly “Father’s Day” to the bloody, beastly conclusion of “The Box,” which features the death of a truly irritating Adrienne Barbeau. But the highlight is a murderous Leslie Nielsen, in the sort of pompous, villainous performance that fans of The Naked Gun or Airplane! have likely never seen before. You owe it to yourself to see Creepshow for him alone. —Jim Vorel

90. Black Christmas, 1974Director: Bob Clark

Fun fact—nine years before he directed holiday classic A Christmas Story, Bob Clark created the first true, unassailable “slasher movie” in Black Christmas. Yes, the same person who gave TBS its annual Christmas Eve marathon fodder was also responsible for the first major cinematic application of the phrase “The calls are coming from inside the house!” Black Christmas, which was insipidly remade in 2006, predates John Carpenter’s Halloween by four years and features many of the same elements, especially visually. Like Halloween, it lingers heavily on POV shots from the killer’s eyes as he prowls through a dimly lit sorority house and spies on his future victims. As the mentally deranged killer calls the house and engages in obscene phone calls with the female residents, one can’t help but also be reminded of the scene in Carpenter’s film where Laurie (Jamie Lee Curtis) calls her friend Lynda, only to hear her strangled with the telephone cord. Black Christmas is also instrumental, and practically archetypal, in solidifying the slasher legend of the so-called “final girl.” Jessica Bradford (Olivia Hussey) is actually among the better-realized of these final girls in the history of the genre, a remarkably strong and resourceful young woman who can take care of herself in both her relationships and deadly scenarios. It’s questionable how many subsequent slashers have been able to create protagonists who are such a believable combination of capable and realistic. —Jim Vorel

89. The Stuff, 1985Director: Larry Cohen

A cult classic for sure, The Stuff was one of the best 1980s critiques of consumer culture, all wrapped up in the form of a horror movie. Profiteers find a white, gooey substance leaking up out of the Earth that proves both delicious and addictive…which they discover by simply tasting this stuff seeping up from the ground, in what is definitely a doctor-recommended action. Soon, repackaged as the secret ingredient-laden “Stuff,” it sweeps the world. The fake commercials are fantastic—this one has Abe Vigoda and actress Clara Peller, who only one year earlier began the famous “Where’s the beef?” campaign for Wendy’s. That is cross-cultural awareness. The Stuff is also a very fun, schlocky horror flick with gross-out special effects, because as you eat more of The Stuff it gradually takes over your body until it explodes out into a self-aware being. This film may actually be more relevant today than it was in the mid-1980s, as awareness of what’s actually in fast food becomes more widespread. —Jim Vorel

88. The Invitation, 2016Director: Karyn Kusama

The less you know about Karyn Kusama’s The Invitation, the better. This is true of slow-burn cinema of any stripe, but Kusama slow-burns to perfection. In this case, that involves a tale of deep and intimate heartache, the kind that none of us hopes to ever have to endure in their own lives. The film taps into a nightmare vein of real-life dread, of loss so profound and pervasive that it fundamentally changes who you are as a human being. That’s where we begin: with an examination of grief. The film starts in earnest as Will (Logan Marshall-Green in top form) arrives at a dinner party his ex-wife, Eden (Tammy Blanchard), is throwing at what once was their house. He has brought his girlfriend, Kira (Emayatzy Corinealdi), along with him. But something is undeniably off at Eden’s place, and because Will is the lens through which Kusama’s audience engages with the film, we cannot tell what that something is. Still, it is, in point of fact, frequently hard to root for Will, or to level with his perspective. He skulks around the hallways of Eden’s home, rooting around through her nightstand drawers, looking for something, anything, to assure himself of, well, what exactly? That she’s just as torn up inside as he is over the tragedy that split them up years prior? That she hasn’t actually moved on from him, from the life they once shared together?

We don’t know. Will probably doesn’t either. And that’s okay: Knowing isn’t part of what makes The Invitation so nerve-racking and pleasing as a sophisticated exercise in genre.

There is oh so much more to be said about The Invitation, especially its climax, where all is revealed and we see Will’s fears and Eden’s spiritual affirmations for what they are. Until then you’ll remain on tenterhooks, but to Kusama, jitters and thrills are sensations worth savoring. Where we end? The Invitation is remarkable neither for its ending nor for the direction we take to arrive at its ending. Instead, it is remarkable for its foundation, for all of the substantive storytelling infrastructure that Kusama builds the film upon in the first place. —Andy Crump

87. Lake Mungo, 2008Director: Joel Anderson

Lake Mungo could scarcely be more different from something like Grave Encounters—there are no ghosts or demons chasing screaming people down the hall, and it’s chiefly a story about family, emotion and our desire to seek closure after death. You could call it a member of the “mumblegore” family, without the gore. It centers around a family that has been shattered by a daughter’s drowning, and the family’s subsequent entanglement in what may or may not be a haunting, and the mother’s desire to determine what kind of life her daughter had been living. Powerfully acted and subtly shot, it’s a tense (if grainy) family drama with hints of the supernatural drifting around the fraying edges of their sanity. If there’s such a thing as “horror drama,” this documentary-style film deserves the title. —Jim Vorel

86. Goodnight Mommy, 2014Directors: Veronika Franz, Severin Fiala

We begin by joining twin, tow-headed nine-year-old brothers Lukas (Lukas Schwarz) and Elias (Elias Schwarz) as they explore the rural paradise of their new home, swimming in azure-pure lakes and casually spelunking through nearby caves ostensibly untouched for centuries. Though the twins seem to be perfectly content letting their Edenic nature occupy them, a near-ineffable pall of tragedy hangs over the film from the start. It’s unexplainable but slightly pungent, as if at any moment one of the boys will fall down a ravine or stumble into a hornet’s nest. Maybe it’s because they bow to seemingly no adult supervision—that is, until their mother (Susanne Wuest) returns to their ceaselessly modern home after going away for a surgery of some sort. Her face covered in bandages, her eyes red-rimmed and limned with a shadow of dread, “Mommy” greets her boys with reticence and anxiety. Gradually, of course, the boys suspect that something is up with their mommy, especially when, as a form of punishment for their suspicious behavior (as well as, we assume, behavior and transgressions we have yet to understand), she pretends that Lukas doesn’t exist.

Goodnight Mommy, for all of its familiar notions, isn’t exactly a traditional horror film, more in tune with the eerie, silent moral plays of Carl Theodor Dreyer than with the Grand Guignol schlock of an Eli Roth in heat. In fact, you may be able to figure out the “twist” by the end of the first act; while the filmmakers do nothing to bury the lede, they still take great pains to juggle their high-minded concept with an eye for burrowing certain notions about the very fabric of our human race within the subcutaneous folds of our most firmly held beliefs about how life—family, love, trust—should work. The true horror of Goodnight Mommy isn’t about who she is, but what happens to her—how easily we can set fire to the bedrock of even our basest notions of what it means to be human. And there really is nothing scarier than that. —Dom Sinacola

85. Carnival of Souls, 1962Director: Herk Harvey

Carnival of Souls is a film in the vein of Night of the Hunter: artistically ambitious, from a first-time director, but largely overlooked in its initial release until its rediscovery years later. Granted, it’s not the masterpiece of Night of the Hunter, but it’s a chilling, effective, impressive little story of ghouls, guilt and restless spirits. The story follows a woman (Candace Hilligoss) on the run from her past who is haunted by visions of a pale-faced man, beautifully shot (and played) by director Herk Harvey. As she seemingly begins to fade in and out of existence, the nature of her reality itself is questioned. Carnival of Souls is vintage psychological horror on a miniscule budget, and has since been cited as an influence in the fever dream visions of directors such as David Lynch. To me, it’s always felt something like a movie-length episode of The Twilight Zone, and I mean that in the most complimentary way I can. Rod Serling would no doubt have been a fan. —Jim Vorel

84. The Host, 2006Director: Bong Joon-ho

Before he was breaking out internationally with a tight action film like Snowpiercer, and eventually winning a handful of Oscars for Parasite, this South Korean monster movie was Bong Joon-ho’s big work and calling card. Astoundingly successful at the box office in his home country, it straddles several genre lines between sci-fi, family drama and horror, but there’s plenty of scary stuff with the monster menacing little kids in particular. Props to the designers on one of the more unique movie monsters of the last few decades—the mutated creature in this film looks sort of like a giant tadpole with teeth and legs, which is way more awesome in practice than it sounds. The real heart of the film is a superb performance by Song Kang-ho (also in Snowpiercer and Parasite) as a seemingly slow-witted father trying to hold his family together during the disaster. That’s a pretty common role to be playing in a horror film, but the performances and family dynamic in general truly are the key factor that help elevate The Host far above most of its ilk. —Jim Vorel

83. The Bad Seed, 1956Director: Mervyn LeRoy

The Bad Seed is one of the most disturbing American portraits of pure psychopathy or sociopathy, coming from the least suspected of all sources: an 8-year-old girl. The piercing eyes of little blonde, pigtailed Rhoda (Patty McCormack) are terrifying to behold, moreso once we begin to suspect what lays behind her facade. Rhoda’s ability to function and hide her true self with wily cunning presages the likes of Patrick Bateman or the already mentioned Henry in Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. There could be no We Need to Talk About Kevin without The Bad Seed there to ask the question: What is the nature of innate evil? The menace and sheer, unflinching look into human cruelty in The Bad Seed is truly unique for its time period, with young McCormack’s performance ranking among the all-time greats for children in a horror film. The Bad Seed is about the horrors of responsibility as a parent, when there’s something you know needs to be done but the act of carrying it out is something the world will never be able to understand. It’s a film that may turn you off of pigtails for life. —Jim Vorel

82. Society, 1989Director: Brian Yuzna

Society is perhaps what you would have ended up with in the earlier ’80s if David Cronenberg had a more robust sense of humor. Rather, this bizarre deconstruction of Reagan-era yuppiehood came from Brian Yuzna, well-known to horror fans for his partnership with Stuart Gordon, which produced the likes of Re-Animator and From Beyond…and eventually Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, believe it or not. Society is a weird film on every level, a feverish descent into what may or may not be paranoia when a popular high school guy begins questioning whether his family (and indeed, the entire town) are involved in some sinister, sexual, exceedingly icky business. Plot takes a backseat to dark comedy and a creepily foreboding sense that we’re building to a revelatory conclusion, which absolutely does not disappoint. The effects work, suffice to say, produces some of the most batshit crazy visuals in the history of film—there are disgusting sights here that you won’t see anywhere else, outside of perhaps an early Peter Jackson movie, a la Dead Alive. But Society’s ambitions are considerably grander than that gross-out Peter Jackson classic—it takes aim at its own title and the tendency of insular communities to prey upon the outside world to create social satire of the highest (and grossest) order. —Jim Vorel

81. Friday the 13th, 1980Director: Sean S. Cunningham

The one that started them all: Years after two summer camp counselors are offed while they’re getting it on, a new group with similar extracurricular activities arrives at Camp Crystal Lake. Hack, slice. A pre-Footloose Kevin Bacon (one of the series’ many casting gems) plays a guy who gets lucky and then immediately gets an arrowhead through the back of the throat. Bummer. Friday the 13th is a competent and formative slasher flick, though it barely resembles the series it spawned, in ways both positive and negative. Its impact, however, can’t be argued, and it’s the film most singularly responsible for properly kicking off the slasher boom of the ’80s. Jason makes only a brief, but extremely searing appearance, and the film’s ending reveal can be counted among the most shocking in horror history. —Jeffrey Bloomer

80. We Are Still Here, 2015Director: Ted Geoghegan

We Are Still Here never wants for scares. It might actually be the single most terrifying movie of 2015, even next to David Robert Mitchell’s acclaimed and unsettling It Follows. But Geoghegan handles the transition smoothly, from the story of running away from tragedy We Are Still Here begins as to the bloodbath it becomes. There’s no sense of baiting or switching; the director flirts with danger confidently throughout. Plus, there’s that New England winter to add an extra layer of despair. The elements forebode and forbid in equal measure. The weather outside is frightful…and the carbonized wraiths in the basement even more so. In the end, this is one haunted house that won’t be denied. —Andy Crump

79. The Curse of Frankenstein, 1957Director: Terence Fisher

The film that birthed the stylistic idea of “Hammer Horror” and brought back the greatest of the Universal Monsters to the mainstream: It’s Curse of Frankenstein. And it’s difficult to do justice to how important a moment this was for the future course of horror history, the effective launching point of a second Golden Age of serious monster movies. In the ’40s and ’50s, classical horror had been in decline, co-opted by comedies such as Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein or the burgeoning science fiction genre. It was Curse of Frankenstein and Hammer’s subsequent Dracula and Mummy follow-ups that convinced audiences the old monsters could once again be treated as the stuff of nightmares, and they did so by infusing the old black-and-white specters with opulence, cleavage and pulses of Technicolor blood that brought shock and titillation back to the genre. Unlike the Universal series, the Hammer Frankenstein films make no qualms about the identity of the true villain—it’s the Doctor himself, played with petulant verve by the great Peter Cushing. He morphs into something of an antihero throughout the sequels, but this imperious Frankenstein, who thinks he simply knows better than the foolish, close-minded villagers impeding his work, is the obvious spiritual forebear to Jeffrey Combs’ Herbert West in Re-Animator. Christopher Lee’s monster, on the other hand, is an afflicted creature without the soul or humanity of Karloff’s iconic creation. We fear him, and pity him, but this is Cushing’s time to shine and revel in his own crapulence. —Jim Vorel

78. Hereditary, 2018Director: Ari Aster

Ari Aster’s debut film begins in miniature. Later we learn of the trade Annie (Toni Collette), the film’s family’s matriarch, plies—meticulously designing doll-house-sized vignettes of the many domestic traumas she’s experienced, and still does, throughout her life, not for children but for art gallery spaces—though in the moment, in the beginning of Hereditary, the effect simply alludes to Aster’s ancestral preoccupations. From a tree house, pulling back through Annie’s workshop window, cinematographer Pawel Pogorzelski’s camera pans to a tiny recreation of the house we’re currently within, then pushes into the simulacrum of high school student Peter Graham’s (Alex Wolff) bedroom, which transforms into the room itself, perspectives already ruined so early in the film. Father Steve (Gabriel Byrne) enters to give his late-snoozing son the black suit needed to attend his late grandmother’s memorial. Aster’s intent, as is the case throughout Hereditary, is both blunt and oblique: worlds exist within worlds, shadows within that which casts them, or vice versa, reality represented like the rings of a tree or the spirals of DNA holding untold secrets within the cores of whoever we are. Colin Stetson’s brain-churning score rattles the frame’s edges. Menace looms—and menace soon unfolds, tragedies upon tragedies. The Graham family unravels over the course of Hereditary, which derives its power from testing the binds that force families together, teasing their strength as each family member must confront, kicking and screaming (or in Collette’s case: making the noise of one’s soul fleeing through every orifice), just how superficial those binds can be. In the absence of a reason for all of this happening, there is inevitability; in the absence of resolution there is only acceptance. —Dom Sinacola

77. A Dark Song, 2017Director: Liam Gavin

In Liam Gavin’s black magic genre oddity, Sophia (Catherine Walker), a grief-stricken mother, and the schlubby, no-nonsense occultist (Steve Oram) she hires devote themselves to a long, meticulous, painstaking ritual in order to (they hope) communicate with her dead son. Gavin lays out the ritual specifically and physically—over the course of months of isolation, Sophia undergoes tests of endurance and humiliation, never quite sure if she’s participating in an elaborate hoax or if she can take her spiritual guide seriously when he promises her he’s succeeded in the past. Paced to near perfection, A Dark Song is ostensibly a horror film but operates as a dread-laden procedural, mounting tension while translating the process of bereavement as patient, excruciating manual labor. In the end, something definitely happens, but its implications are so steeped in the blurry lines between Christianity and the occult that I still wonder what kind of alternate realms of existence Gavin is getting at. But A Dark Song thrives in that uncertainty, feeding off of monotony. Sophia may hear phantasmagorical noise coming from beneath the floorboards, but then substantial spans of time pass without anything else happening, and we begin to question, as she does, whether it was something she did wrong (maybe, when tasked with not moving from inside a small chalk circle for days at a time, she screwed up that portion of the ritual by allowing her urine to dribble outside of the boundary) or whether her grief has blinded her to an expensive con. Regardless, that “not knowing” is the scary stuff of everyday life, and by portraying Sophia’s profound emotional journey as a humdrum trial of physical mettle, Gavin reveals just how much pointless, even terrifying work it can be anymore to not only live the most ordinary of days, but to make it to the next. —Dom Sinacola

76. The Nightmare, 2015Director: Rodney Ascher

The Nightmare may very well lay claim to the title of the most purely frightening documentary film ever made. Yes, it’s a documentary, from Rodney Asher, director of the similarly horror-themed doc Room 237. The simple structure of the film involves in-depth interviews with eight people who all suffer from some form of sleep paralysis, describing the horrifying visions they encounter on a nightly basis. It’s equal parts tragic and chilling to hear how the condition has made their nighttime hours into living hells, and legitimately frightening to watch those scenes reenacted. On the other hand, the documentary is frustrating at times for not asking or answering what seem like fairly obvious questions: Does medication aid with these sleep paralysis episodes? Have any of the subjects of the documentary ever been studied in an overnight sleep study? Personally, this is a fear I’ve always dreaded experiencing, so if you’re anything like me, you’ll agree with the subject who describes his experiences as “the kind of horror that is worse than movies.” That sounds bad enough, but then there’s the guy who describes experiencing sleep paralysis immediately after being told about sleep paralysis, purely by suggestion. That will really freak you out. Don’t watch The Nightmare before falling asleep. —Jim Vorel

75. The Cabin in the Woods, 2012Director: Drew Goddard

When drafting this list of 100, we decided to keep horror comedies by and large out of the fold—this is a list of “horror films,” pure and simple. There was no room for beloved parodies such as Shaun of the Dead, but The Cabin in the Woods is the exception that proves the rule, capable in some moments of being frightening while primarily functioning as one of the best-crafted meta-commentaries that the genre has ever seen. It’s shocking that Drew Goddard hasn’t directed a film since, even though he’s been flying high while penning the likes of The Martian. But his deep knowledge and clearly slavish devotion to the tropes of the horror genre that are on display in Cabin in the Woods, which neatly breaks down the “five man band” of camp-style slashers while being simultaneously uproarious and gratifyingly unique. Another film that sat in development hell after completion because studios weren’t sure how to market it, the movie can probably thank the Hollywood ascendancy of Chris Hemsworth for the fact that it eventually got a release, but the powerhouse performances come from Kristen Connolly, Fran Kranz, and especially Bradley Whitford and Richard Jenkins, whose wry commentary as this horror story’s puppet masters is indispensable and never short of side-splitting. In the end, it’s the little things that Cabin in the Woods does so right—from the properly grizzled “harbinger” who warns the kids of their impending doom, to the running jokes around mermaids that finally see themselves to a very satisfying conclusion. Every loose thread is accounted for en route to a decidedly punk rock finale. —Jim Vorel

74. REC (2007)Director: Jaume Balagueró and Paco Plaza

2007 was a breakthrough year for post-Blair Witch found footage horror, including the first Paranormal Activity and George Romero’s Diary of the Dead, but it wasn’t only in the U.S. that people were effectively employing that technique. The best of all the found-footage zombie films is still probably REC, another film on this list that exhibits some playfulness in re-determining exactly what a “zombie” is or isn’t. The Spanish film follows a news crew as they sneak inside a quarantined building experiencing the breakout of what appears to be a zombie plague. The fast-moving infected resemble those of 28 Days Later, later revealed to be demonically possessed in a way that moves through bites, ably blending traditional zombie lore and religious mysticism. REC is a capable, professional-feeling film for its low budget, and there are some excellently choreographed scenes of zombie mayhem that feel all the more claustrophobic for being filmed in a limited, first-person viewpoint. Zombie horror seems to go hand-in-hand with the found-footage approach more naturally than some other horror genres—perhaps it’s the fact that in the digital age, we’d all be compelled to document any such outbreak on our phones or other devices? Regardless, REC isn’t nearly so forced as some entries in this particular horror subgenre, and gives an excellent sense of what it might be like if you were just an average person locked in a huge apartment building filled with zombies. —Jim Vorel

73. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, 1986Director: John McNaughton

Henry stars Merle himself, Michael Rooker, in a film which is essentially meant to approximate serial killer Henry Lee Lucas, along with his demented sidekick Otis Toole (Tom Towles). The film was shot and set in Chicago on a budget of only $100,000, and is a depraved journey into the depths of the darkness capable of infecting the human soul. That probably sounds like hyperbole, but Henry really is an ugly film—you feel dirty just watching it, from the filth-crusted urban streets to the supremely unlikeable characters who prey on local prostitutes. It’s not an easy watch, but if gritty true crime is your thing, it’s a must-see. Some of the sequences, such as the “home video” shot by Henry and Otis as they torture an entire family, gave the film a notorious reputation, even among horror fans, as an unrelenting look into the nature of disturbingly mundane evil. —Jim Vorel

72. Opera, 1987Director: Dario Argento

Giallo is not the kind of genre in which directors end up receiving a lot of critical aplomb—with the occasional exception of Dario Argento. He is to the bloody, Italian precursor to slasher films as, say, someone like Clive Barker is to more westernized horrors: an auteur willing to take chances, whose gaudy works are occasionally brilliant but just as often fall flat. Opera, though, is one of Argento’s most purely watchable films, following a young actress (Cristina Marsillach) who seems to have developed a rather homicidal admirer. Anyone who gets in the way of her career has a funny way of ending up dead, and her constant nightmares hint at a long-buried connection to the killer. Essentially the giallo equivalent of Phantom of the Opera, Opera’s canvas is splashed with Argento’s signature color palette of bright, lurid tones and over-the-top deaths. If you love a good whodunnit, and especially if you have an interest in cinematography, Opera is a primer in horror craftsmanship. —Jim Vorel

71. Raw, 2016Director: Julia Ducournau

Julia Ducournau’s Raw is a “coming-of-age movie” in that the film’s protagonist, naive incoming college student Justine (Garance Marillier), comes of age over the course of its running time. She parties, she breaks out of her shell, she learns about who she really is as a person on the verge of adulthood. But most kids who come of age in the movies don’t realize that they’ve spent their lives unwittingly suppressing an innate, nigh-insatiable need to consume raw meat. “Hey,” you’re thinking, “that’s the name of the movie!” Allow Ducournau her cheekiness. More than a wink and nod to the picture’s visceral particulars, Raw is an open concession to the harrowing quality of Justine’s grim blossoming. Nasty as the film gets, and it does indeed get nasty, the harshest sensations Ducournau articulates here tend to be the ones we can’t detect by merely looking: Fear of feminine sexuality, family legacies, popularity politics and uncertainty of self govern Raw’s horrors as much as exposed and bloody flesh. It’s a gorefest that offers no apologies and plenty more to chew on than its effects. —Andy Crump

70. Son of Frankenstein, 1939Director: Rowland V. Lee

Deciding which of the classic Universal Monster movies should be featured on this list proved an incredibly difficult proposition. Notably absent is Tod Browning’s Dracula, a film with discrete, iconic moments but a lack of vitality in the nuts and bolts of its direction and cinematography—a sort of holdover from the silent era, rather than the more vivacious films in the Universal series that follow. But absent also is James Whale’s 1931 classic Frankenstein. Why? Well, despite what you may have heard, Frankenstein may very well be the third best film of its own series, surpassed not only by the well-recognized Bride of Frankenstein but also by the much less appreciated Son of Frankenstein as well. Director James Whale and original Dr. Colin Clive have moved on, the latter replaced by classic Sherlock Holmes portrayer Basil Rathbone as our new protagonist, Wolf Frankenstein, who returns to his father’s ancestral castle only to find that the legendary monster isn’t quite as dead as he’s been led to believe. Bela Lugosi, of all people, enters the series as the first Frankenstein character called “Igor” (although it’s actually “Ygor”), a ghoulish caretaker who claims to literally be undead—hanged by the villagers and sustaining a broken neck, but somehow not dying. His master plan: To use Wolf’s scientific knowledge to resurrect the monster (Boris Karloff, one final time) and then use the monster as a tool of vengeance to hunt down the men who hanged him. With cavernous, opulent sets in Frankenstein manor, Son of Frankenstein is a lush, prestigious-feeling production that boasts masterful performances from Rathbone, the one-armed inspector (parodied in Young Frankenstein) played by Lionel Atwill and especially from Lugosi, who is at his absolute best in a role that is far more nuanced than that of Dracula. With its gorgeous, gothic visuals and expanded run-time, Son of Frankenstein is the secret crown jewel of the entire Universal Monster series. —Jim Vorel

69. Zombi 2, 1979Director: Lucio Fulci

In the ’70s and ’80s, it was hard to beat Italy in terms of fucked-up horror movie content, and given that market’s fondness for the “cannibal film,” is it any surprise they also came to love the zombie genre as well? Zombi 2 is the epitome of all the Italian zombie movies, cleverly implied as essentially a direct follow-up (thematically, not plot-wise) to Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, which had been released in Italy to great success under the title Zombi. Helmed by Italian giallo/supernatural horror maestro Lucio Fulci, Zombi 2 significantly upped the crazy factor and pushed gore to a new ceiling. The film’s effects and makeup are absolutely disgusting, and it’s filled with iconic moments that have transcended the horror genre. Scene of someone having an eye poked out? They’re always compared to the eye-poking scene in Zombi 2. Scene where a zombie fights a freaking SHARK? Well, nobody compares that, because nobody has the balls to try and one-up Zombi 2’s zombie shark-fighting scene. That’s one contribution that will stand the test of time. —Jim Vorel

68. Dead & Buried, 1981Director: Gary Sherman

Dead & Buried is a thoroughly unusual horror film that revolves around the reanimated dead, but in a way all its own. In a small New England coastal town, a rash of murders breaks out among those visiting. Unknown to the town sheriff (James Farentino), those bodies never quite make it to their graves—though people who look just like the murdered visitors are walking the streets as permanent residents. The zombies here are different from most similar movies in the genre in their autonomy and ability to pass for human, although they do answer to a certain leader…but who is it? Dead & Buried is part murder mystery, part cult story and part zombie flick, featuring some absolutely revolting creature work and gore from the legendary Stan Winston. It’s got a feel all its own, and one notable for some unusual casting choices, including a pre-Nightmare on Elm Street Robert Englund as one of the possibly zombified town locals, and, in a major role, Jack Albertson (Grandpa Joe from Willy Wonka) as the eccentric, jazz-loving town coroner/mortician, who steals every scene he’s in. More people should seek out this weird little film. —Jim Vorel

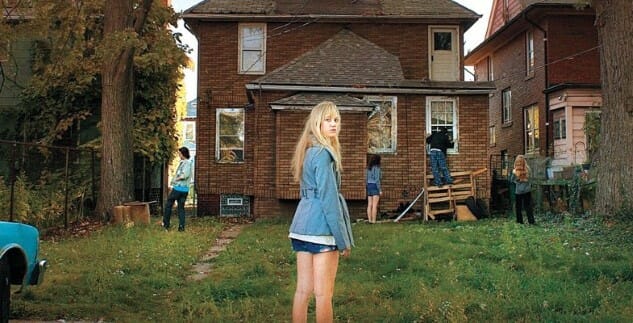

67. It Follows, 2015Director: David Robert Mitchell

The specter of Old Detroit haunts It Follows. In a dilapidating ice cream stand on 12 Mile, in the ’60s-style ranch homes of Ferndale or Berkley, in a game of Parcheesi played by pale teenagers with nasally, nothing accents—if you’ve never been, you’d never recognize the stale, gray nostalgia creeping into every corner of David Robert Mitchell’s terrifying film. But it’s there, and it feels like SE Michigan. The music, the muted but strangely sumptuous color palette, the incessant anachronism: In style alone, Mitchell is an auteur seemingly emerged fully formed from the unhealthy womb of Metro Detroit. Cycles and circles concentrically fill out It Follows, from the particularly insular rules of the film’s horror plot, to the youthful, fleshy roundness of the faces and bodies of this small group of main characters, never letting the audience forget that, in so many ways, these people are still children. In other words, Mitchell is clear about his story: This has happened before, and it will happen again. All of which wouldn’t work were Mitchell less concerned with creating a genuinely unnerving film, but every aesthetic flourish, every fully circular pan is in thrall to breathing morbid life into a single image: someone, anyone slowly separating from the background, from one’s nightmares, and walking toward you, as if Death itself were to appear unannounced next to you in public, ready to steal your breath with little to no aplomb.

Initially, Mitchell’s whole conceit—passing on a haunting through intercourse—seems to bury conservative sexual politics under typical horror movie tropes, proclaiming to be a progressive genre pic when it functionally does nothing to further our ideas of slasher fare. You fornicate, you find punishment for your flagrant, loveless sinning, right? (The film has more in common with a Judd Apatow joint than you’d expect.) Instead, Mitchell never once judges his characters for doing what practically every teenager wants to do; he simply lays bare, through a complex allegory, the realities of teenage sex. There is no principled implication behind Mitchell’s intent; the cold conclusion of sexual intercourse is that, in some manner, you are sharing a certain degree of your physicality with everyone with whom your partner has shared the same. That he accompanies this admission with genuine respect and empathy for the kinds of characters who, in any other horror movie, would be little more than visceral fodder for a sadistic spirit, elevates It Follows from the realm of disguised moral play into a sickly scary coming-of-age tale. Likewise, Mitchell inherently understands that there is practically nothing more eerie than the slightly off-kilter ordinary, trusting the film’s true horror to the tricks our minds play when we forget to check our periphery. It Follows is a film that thrives in the borders, not so much about the horror that leaps out in front of you, but the deeper anxiety that waits at the verge of consciousness—until, one day soon, it’s there, reminding you that your time is limited, and that you will never be safe. Forget the risks of teenage sex, It Follows is a penetrating metaphor for growing up. —Dom Sinacola

66. Near Dark, 1987Director: Kathryn Bigelow

Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark was one of her first films with a decent budget, and she invested those funds wisely into making a moody, pulpy vampire Western with an excellent supporting cast, from the iconic Bill Paxton (whose character’s demise is beautiful) to horror staple Lance Henriksen in one of his higher-profile appearances outside Aliens. It’s a film that really drives home the light vs. shadow, day vs. night aspect of the vampire psyche and physiology. So much of the movie, in fact, involves the biker gang-like vampires laying low, hiding from both sunlight and the human police, their existence hardly “romanticized” at all. In fact, these vampires project more of a tragic streak than anything: They’re outlaws who have convinced themselves that they’re living a life of freedom and immortality when their existence is actually fragile and just a blast of UV light away from being cut short. Near Dark is like one of the many ’70s-era Hells Angels biker films—a Wild Rebels where the vampires are those doomed outsiders who live fast and die (relatively) young. —Jim Vorel

65. The Beyond, 1981Director: Lucio Fulci

The Beyond may be the best of Lucio Fulci’s non-zombie movies. Which isn’t to say there aren’t any zombies in it, but it’s not a Romero-style zombie movie, like the former. The Beyond is the middle entry in Fulci’s “Gates of Hell” trilogy, and takes place in and around a crumbling old hotel that just happens to have one of those gates to Hell located in its cellar. When it opens, all Hell—of course—starts to break loose in the building, in a film that combines a haunted house aesthetic with demonic possession, the living dead and ghostly apparitions. As with so many of the other films in this mold, it’s not always entirely clear what’s going on—and honestly, the plot is more or less irrelevant. You’re watching it to see demons gouge people’s eyes out or watch heads being blown off, and there’s no shortage of either. Thinking back to Lucio Fulci movies after the fact, you won’t remember any of the story structure, you’ll just remember the ultra gory highlights, splattering across the screen in a way that continues to influence filmmakers to this day. —Jim Vorel

64. Cat People, 1942Director: Jacques Tourneur

To this day, it doesn’t seem entirely fair that so much credit for Cat People is almost universally given to producer Val Lewton, rather than director Jacques Tourneur or writer DeWitt Bodeen, but it’s true of the entire run of low-budget horror films that Lewton produced at RKO. Regardless, Cat People was a populist hit in its day before being reevaluated decades later as a landmark of ’40s horror. In stark contrast to Universal’s monster movies of the same era, it leans on suspense and carefully constructed shots rather than Jack Pierce makeup to make an impression. The story of a young Russian immigrant (Simone Simon) with a dark family past, Cat People combines aspects of film noir and mystery movies with Hitchcockian suspense, while pioneering several staple tropes of horror cinema that have been used hundreds, if not thousands of times since. In particular, the scene with a young woman walking home on a dark night, stalked by an unseen presence, builds to an unexpected conclusion that must have made audiences in 1942 come jumping out of their seats. —Jim Vorel

63. Horror of Dracula, 1958Director: Terence Fisher

Horror of Dracula is either the second or third most iconic “classic vampire” film ever made, trailing only the 1931 Bela Lugosi Dracula and possibly the original Nosferatu. But really, if you were going to put together the ultimate, time-spanning Dracula film, you’d choose this version of the vampire, as played by the regal, intimidating Christopher Lee at the height of his powers. Horror of Dracula is simply a gorgeous movie, with lush, gothic settings—crypts, foggy graveyards and stately manors—photographed with the Golden Age charm of Technicolor. It has the best version of Van Helsing ever put to film (the aquiline, gaunt-looking Peter Cushing), some of the best sets and an omnipresent feeling of refinement and grandeur. Dracula, as played by Lee, is a creature of dualities—preferring to use very few words and simply influence through his magnetic presence, but also just moments away from leaping into action with ferocious animality. Along with Curse of Frankenstein, Horror of Dracula is the film most responsible for the late ’50s to early ’70s revival of classic gothic horror via Hammer Film Productions in the UK, which would produce dozens of takes on Frankenstein, The Mummy, and no fewer than eight Dracula sequels. The first, however, is unquestionably the best—so effective that it typecast Christopher Lee as a horror icon for decades, exactly as Dracula did to Bela Lugosi. —Jim Vorel

62. The Omen, 1976Director: Richard Donner

In the canon of “creepy kid” movies, the original 1976 incarnation of The Omen stands alone, untainted by the horrendous 2006 remake. It has a palpable sense of malice to it, largely because of the juxtaposition of restraint and moments of extremity. Damien (Harvey Spencer Stephens) isn’t this little devil boy running around stabbing people, he’s full of guile, deceit and, scariest of all, patience. He knows that he’s playing the long game—it will be years and years before he achieves his purpose on the Earth, which gives him the uncomfortable attitude of an adult (and a pure evil one) in a child’s body. The film is brooding, sullen, broken up by staccato moments of shocking violence. In particular are the infamous scene wherein a sheet of glass leads to a decapitation, or the fate of Damien’s nurse in the film’s opening. The Omen can genuinely can get under your skin, especially if you’re a parent. —Jim Vorel

61. Ginger Snaps, 2000Director: John Fawcett

Ginger Snaps is a high school werewolf story, but before you go making any Twilight comparisons, let me state for the record: Where Twilight is maudlin, Ginger Snaps is vicious. A pair of death-obsessed, outsider sisters, Ginger and Brigitte, are faced with issues of maturation and sexual awakening when Ginger (Katharine Isabelle) is bitten by a werewolf. As she begins to become bolder and more animalistic in her desires, the second, meeker sister (Emily Perkins) searches for a way to reverse the damages before Ginger carves a path of destruction through their community. Reflecting the influence of Cronenberg-style body horror and especially John Landis’s American Werewolf in London, Ginger Snaps is a surprisingly effective horror movie and mix of drama/black comedy that brought the werewolf mythos into suburbia in the same sort of way Fright Night managed to do so with vampires. It also made a genre star of Isabelle, who has since appeared in several sequels and above average horror flicks such as American Mary. Even if the condition of lycanthropism is an obvious parallel to the struggles of adolescence and puberty, Ginger Snaps is the one film that has taken that rich vein of source material and imbued it with the same kind of punk spirit as Heathers. – —Jim Vorel

60. Les Diaboliques, 1955Director: Henri-Georges Clouzot

Watching Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les Diaboliques through the lens of the modern horror film, especially the slasher flick—replete with un-killable villain (check); ever-looming jump scares (check); and a “final girl” of sorts (check?)—one would not have to squint too hard to see a new genre coming into being. You could even make a case for Clouzot’s canonization in horror, but to take the film on only those terms would miss just how masterfully the iconic French director could wield tension. Nothing about Les Diaboliques dips into the scummy waters of cheap thrills: The tightly wound tale of two women, a fragile wife (Véra Clouzot) and severe mistress (Simone Signoret) to the same abusive man (Paul Meurisse), who conspire to kill him in order to both reel in the money rightfully owed the wife, and to rid the world of another asshole, Diaboliques may not end with a surprise outcome for those of us long inured to every modern thriller’s perfunctory twist, but it’s still a heart-squeezing two hours, a murder mystery executed flawlessly. That Clouzot preceded this film with The Wages of Fear and Le Corbeau seems as surprising as the film’s outcome: By the time he’d gotten to Les Diaboliques, the director’s grasp over pulpy crime stories and hard-nosed drama had become pretty much his brand. That the film ends with a warning to audiences to not give away the ending for others—perhaps Clouzot also helped invent the spoiler alert?—seems to make it clear that even the director knew he had something devilishly special on his hands. —Dom Sinacola

59. Misery, 1990Director: Rob Reiner

Although most writers are more likely to experience “misery” over the persistent belief that no one cares about their work, Rob Reiner’s adaptation of Stephen King’s novel reminds us that sometimes there is an upside to obscurity. James Caan plays Paul Sheldon, author of a popular series of Regency bodice-rippers featuring a protagonist named Misery Chastain. Eager to embark on a more serious phase of his career and leave Misery behind (as it were), he’s knocked unconscious in a snowstorm car crash and wakes up in the remote home of a nurse named Annie Wilkes (Kathy Bates), who’s rescued him. And by rescued I mean abducted. Annie’s not such a nice lady, as it turns out, and being stuck with broken legs in the remote hideaway of a violent stalker-superfan has some disadvantages. Reiner is better known as a director of comedies, and even in a horror film he’s not shy about grabbing a cheap laugh: Sometimes it’s hard to tell how seriously we’re supposed to take Bates as a monster, as she careens from sledgehammer-wielding psychopath to Liberace-adoring…um, psychopath. Overall, though, it’s a powerful trope, being helpless and at the mercy of someone who might snap at any second. Stephen King’s written a lot of horror stories, many of which have become commercially successful films, but this one just might be the best of his adaptations, in part due to the stellar performances by Caan and Bates (who won the Oscar for Best Actress for her portrayal of the unhinged Annie), but it’s also pretty fabulous as a meta-meditation on the nature of fame, isolation and obsession, especially if you happen to be a writer. It’s not a terribly profound film, but it has some serious audacity and a kind of simultaneously cerebral and visceral tension that reminds us that sometimes the real horrors aren’t paranormal—sometimes the mundane monsters are the truly scary ones. —Amy Glynn

58. Trick ’r Treat, 2007Director: Michael Dougherty

One might call Trick ’r Treat the best kind of anthology—one that features plenty of disparate, interesting stories, but also ties its stories together in a distinctly satisfying, chronology-bending way. Director Michael Dougherty’s debut film sat on the shelf after being delayed for years, which was a great shame, as it’s far and away the best horror anthology since the 2000s. Somewhat less concerned with outright scares, it’s instead a celebration of Halloween, the idea of the holiday and of fright itself. The stories and characters intertwine on the same small town throughout Halloween night, intersecting in ways both classical (the ghosts of a long ago tragedy return) and modern (a coven of female werewolves, out on the town). Sly comedy and great performances from an array of familiar faces (Brian Cox, Dylan Baker, Anna Paquin) power each of the segments, and none of them overstay their welcome. Indeed, Trick ’r Treat is actually best enjoyed through repeat viewings, which reveal the crossovers between each story even better. In the middle of it all is Sam (Quinn Lord), the disturbing but somehow lovably round-headed spirit of Halloween, who observes in silence and punishes those who trample over the holiday’s traditional observances. It’s seminal “Halloween night” viewing—spooky but approachable, and fun in all the right ways. Here’s hoping that the long-discussed sequel actually shows up one of these days. —Jim Vorel

57. We Need to Talk About Kevin, 2012Director: Lynne Ramsay

We Need To Talk About Kevin concerns the experience of a mother struggling with the aftermath of a school massacre carried out by her son. In its narrative construction, it draws upon two key tropes: that of the “whydunnit” thriller, in which the the mystery of the perpetrator’s motivations are a driving factor, and that of the family horror, in which some dark element tears a traditional household apart. Indeed, the real horror is not that a teenager chose total negation over the banality of normative family life—it’s that these appeared to be the only two choices available. Tilda Swinton is brilliant in the starring role as a mother who grapples with guilt about what her son has done and reflects on his childhood, wondering what, if anything, could possibly have been done differently when one gives birth to a “bad seed.” The heartbreaking nature of the film is perfectly encapsulated by the scene wherein Kevin as a child briefly drops his sociopathic tendencies while ill, giving Swinton’s character a brief chance to feel like a cherished mother, only to emotionally shut her out again as soon as his physical health returns, dashing her hopes that some kind of breakthrough had been made. —Donal Foreman

56. Onibaba, 1964Director: Kineto Shindo

Kaneto Shindo’s Onibaba will make you sweat and give you chills all at once, with its power found in Shindo’s blend of atmosphere and eroticism. It’s a sexy film, and a dangerous film, and in its very last moments a terrifying, unnerving film where morality comes full circle to punish its protagonists for their foibles and their sins. There’s a classicism to Onibaba’s drama, a sense of cosmic comeuppance: Characters do wrong and have their wrongs visited upon them by the powers that be. (In this case, Shindo.) But what makes the film so damn scary isn’t the fear of retribution passed down from on high, it’s the human element, the common thread sewn in a number of modern horror movies where the true monster is always us. Did demons, or demonic idols, foment the civil war that serves as Onibaba’s backdrop? Are spirits culpable for the ruthless survivalism of the film’s two main characters? Nope and nope. Put a checkmark next to “mankind” in reply to both questions, and then wish that demons and spirits were real, because that’d be preferable to acknowledging reality. Back a human into a corner, and they’ll throw you into a ditch, leave you for dead and steal your shit, and what’s more unsettling than “better you than me” as a guiding principle for living? —Andy Crump

55. Starry Eyes, 2014Director: Kevin Kölsch

Starry Eyes is a harrowing film experience, an ordeal, in the same way its protagonist’s journey is a major transformation. At the beginning, you think you have a pretty decent idea of the surface-level points Starry Eyes is trying to make; you get its “Hollywood against Hollywood” bitterness and cynicism about fame and the film industry’s pettiness. Then everything gets so much more destructive and subversive. Sarah (Alex Essoe) is a tragic figure, and this is a “horror tragedy,” if such a thing exists, made worse by the fact that she brings it all onto herself, fueled by deep-seated inadequacy and a crushing lack of self-identity. Her ambition turns her into a monster because she has nothing else: Her life is so devoid of meaning that doing the unthinkable has no downside. Hers, then, is a horrific self-destruction that leads into an abandonment of self and an orgy of truly grotesque violence, but there’s no joy or titillation in any of the ways it’s depicted. No one is going to describe Starry Eyes as light viewing, and no one is going to laugh at the deaths. You don’t show this thing at a party—you dwell on it in the depth of night while self-identifying with its horrors. —Jim Vorel

54. The Vanishing, 1988 Director: George Sluizer

Ever wondered what makes a mastermind like Stanley Kubrick shake in his boots? The answer is The Vanishing, which was apparently the most “terrifying” film he’d ever seen (and this, coming from the guy who made The Shining). In fact, what makes this thriller so unnerving is that it’s told all topsy-turvy: Instead of spending two hours trying to figure out the identity of the bad guy, we’re introduced to him right away. Based on Tim Krabbé’s book The Golden Egg (Het Gouden Ei), the film tells the story of Raymond (Bernard-Pierre Donnadieu), a self-diagnosed sociopath trying to put himself through the ultimate test. Having saved a young girl from drowning, and celebrated as a hero by his daughters, he wants to find out whether his act of kindness can be followed up by a similarly impressive act of evil. As the film allows Raymond to, over time, investigate the line between sociopathy and psychopathy, he spends hours meticulously planning how to best go about abducting a woman, rather than rescuing one. He experiments with chloroform, purchases an isolated house and practices different ways of getting unknowing women to get into his car. Sluizer later remade his own film for American audiences, with Jeff Bridges and Kiefer Sutherland, but its ending was drastically changed. —Roxanne Sancto

53. Black Sabbath, 1963Director: Mario Bava

There was once a time before “Black Sabbath” merely conjured up images of Ozzy Osbourne caterwauling about an “iron man,” “war pigs” or being paranoid over the sounds of Tony Iommi shredding. Indeed, the band in question famously took their name from this celebrated anthology film, which spins three tales of Mario Bava-directed horror. The best is middle chapter, “The Wurdulak,” starring horror icon Boris Karloff as a man who sets out to slay an undead creature (the titular “wurdalak”). To say any more would be to spoil this fascinating and subversive take on the vampire story, an absolute essential totem of the horror genre. —Mark Rozeman

52. We Are What We Are, 2013Director: Jim Mickle

Jim Mickle is the best young horror director to consistently get left out of discussions of “best young horror directors.” His remake of this 2010 Mexican film of the same name is a brooding, tense blend of thriller and horror, the story of a seemingly normal (if stuffy) rural family that harbors a dark secret of religious observances based around yearly acts of cannibalism. When a family member dies and the long-held tradition is threatened, allegiances come into question, familial ties crumble and the younger generation faces an extremely difficult decision in potentially breaking away from the customs that have bound the family together for many generations. It’s part crime story, part grisly, gutsy horror, and features Michael Parks in a role that is about 100 times better than what he was sentenced to do in Kevin Smith’s Tusk. In particular, the conclusion and final 20-30 minutes of We Are What We Are is shocking in both its brutality and emotional impact, an intimate case study of family dysfunction driven by the changing times and the impracticality of archaic traditions that sustain us. Look too closely, and you’ll end up questioning your own familial routine. —Jim Vorel

51. Scream, 1996Director: Wes Craven

Before Scary Movie or A Haunted House were even ill-conceived ideas, Wes Craven was crafting some of the best horror satire out there. And although part of Scream’s charm was its sly, fair jabs at the genre, that didn’t keep the director from dreaming up some of the most brutal knife-on-human scenes in the ’90s. With the birth of the “Ghost Face” killer, Craven took audiences on a journey through horror-flick fandom, making all-too-common tricks of the trade a staple for survival: sex equals death, don’t drink or do drugs, never say “I’ll be right back.” With a crossover cast of Neve Campbell, Courteney Cox, David Arquette, Matthew Lillard, Rose McGowan and Drew Barrymore (OK, for like 10 minutes), Scream arrived with a smart, funny take on a tired genre. It wasn’t the first film of its kind, but it was the first one to be seen by a huge audience, which went a long way in raising the “genre IQ” of the average horror fan. —Tyler Kane

50. The Orphanage, 2007Director: J.A. Bayona

It seems safe to say that director J.A. Bayona was more than a little influenced by Guillermo Del Toro’s The Devil’s Backbone when he laid out The Orphanage, but the film also channels a more stately, gothic brand of horror rather than the dusty, dingy realism of Del Toro’s Spanish Civil War ghost story. Here we have something with a bit more grandeur—a crumbling, seaside mansion that would look out of place if it didn’t have a ghost. Belén Rueda is fantastic as Laura, a woman who moves into the orphanage where she grew up with her husband and young son, before being drawn into the secret history of both the house and the other former orphans who once lived there alongside her. Deep-seated emotion and the impossible desire to protect loved ones from the inevitable permeate the film, but once the home’s restless spirits become active, it’s also quite chilling. Tomás (Oscar Casas), the sack-masked young boy you’ll no doubt see on the DVD cover of The Orphanage, cuts an iconic figure among child ghosts, but it’s the things left unseen that make The Orphanage chilling. The scene featuring a reprise of the knock-knock game once played by the orphans is almost unbearably tense. —Jim Vorel

49. Eyes Without a Face, 1960Director: Georges Franju

I remember seeing my first Édith Scob performance back in 2012, when Leos Carax’s Holy Motors made its way to U.S. shores and melted my pea brain by dint of its surreal meta-text commentary. I also remember Scob donning a seafoam mask, every bit as blank and lacking in expression as Michael Myers’, in the film’s ending, and thinking to myself, “Gee, that’d play like gangbusters in a horror movie.”

What an idiot I was: At the time of my Holy Motors viewing, Scob had already appeared in that movie movie, Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face, an icy, poetic and yet lovingly made film about a woman and her mad scientist/serial killer dad, who just wants to kidnap young ladies that share her facial features in hopes of grafting their skin onto her own disfigured mug. (That’s father of the year material right there.) But of course nothing goes smoothly in the film’s narrative, and the whole thing ends in tears plus a frenzy of canine bloodlust. Eyes Without a Face is played in just the right register of unnerving, perverse and intimate as the most enduring pulpy horror tales tend to be; if Franju gets to claim most of the credit for that, at least save a portion for Scob, whose eyes are the single best special effect in the film’s repertoire. Hers is a performance that stems right from the soul. —Andy Crump

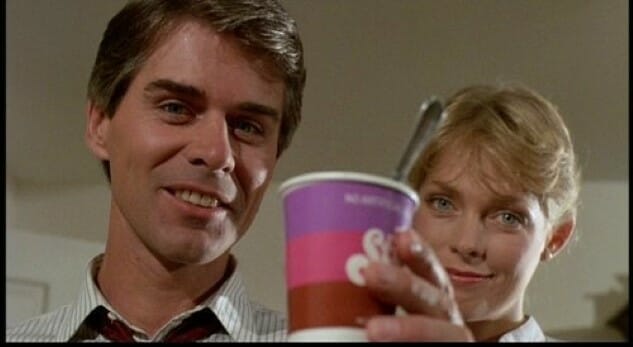

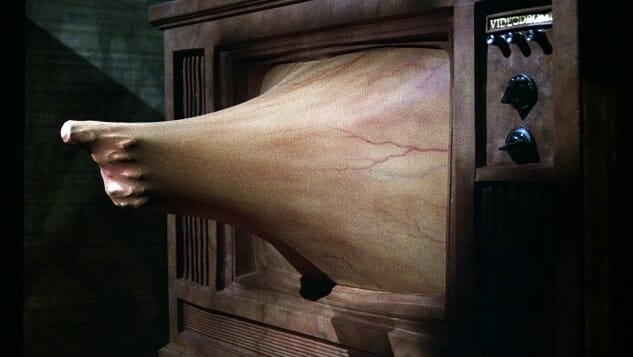

48. Videodrome, 1983Director: David Cronenberg

Videodrome wears many skins: It’s a near-future thriller about the lines between man and machine blurring, a sadomasochistic fantasy, a chronicle of one man’s tragic descent into madness and even a screed against society’s abusive relationship with theatrical violence. Yet, more than any dermis it claims as its own, Videodrome is horror down to its bones, a shard of phantasmagorical mania wielded by the genre’s most cerebral master. The mind is where Cronenberg creeps, taking his imagination’s darkest wanderings—steeped in symbolism and subconscious detritus—to visceral extremes. The same could be said for smut peddler Max Renn (the always sweaty James Woods), manager of a cable TV channel devoted to finding new boundary-breaking entertainment, who stumbles upon a pirated broadcast signal carrying “Videodrome,” a seemingly unsimulated series filled with graphic torture and death. As Cronenberg’s dark dreams tend to do, “Videodrome” begins to warp Renn’s reality—our mind’s eye, as one episode explains to him, is the television screen—and the malevolent forces behind “Videodrome” convince him to go on a killing spree, armed with his newly grown mutant cyborg hand, which might be a hallucination but probably isn’t. Throughout, Cronenberg literalizes Renn’s grossest thoughts, opening up a vaginal orifice in his stomach (into which he salaciously sticks his handgun) or transforming his television set into a pulsating, veined organ, manifesting each apocalyptic vision with immediate, tactile reality. In Videodrome, maybe more saliently than in any of his other films, Cronenberg squeezes the ordeals of the slumbering mind like toothpaste from the tube into the disgusting light of day, unable to push them back in. Long live the new flesh—because the old can no longer hold us together. —Dom Sinacola

47. Black Sunday, 1960Director: Mario Bava

After years spent toiling as a cinematographer and (at times uncredited) co-director on an assortment of moderate to low-budget horror and sword-and-sandals productions, Mario Bava broke out in a big way with Black Sunday. Loosely (and I mean loosely) based on a short story by Nikolai Gogol, the film centers on the resurrection of a 17th century vampire-witch (Barbara Steele) and her paramour (Arturo Dominici) as they seek revenge on the descendants of the brother who executed her. Designed as a throwback to the Universal Monster movies of the 1930s, Black Sunday drew significant controversy for several gruesome sequences (including, but not limited to, the implementation of a spiked death mask and a moment where a cross is stabbed through an eye). Naturally, this kind of notoriety only intensified the film’s popularity. Though time has since lessened the impact of the gorier scenes, the movie still packs a huge punch with its nightmarish atmosphere, which is further accentuated by its vivid black-and-white photography and striking production design. An influence on filmmakers from Tim Burton to Francis Ford Coppola, Black Sunday remains a towering beast in the history of the horror genre. —Mark Rozeman

46. Don’t Look Now, 1973Director: Nicolas Roeg

Don’t Look Now is one of cinema’s great treatises on grief that falls within the realm of horror cinema, an emotionally devastating film that likewise functions as a masterclass on the use of visual and aural leitmotifs. After a married couple (Julie Christie and a typically unhinged Donald Sutherland) loses their sole daughter to a drowning accident, they travel abroad while trying unsuccessfully to cope with the loss, until the wife is contacted by a psychic who claims to be able to speak with their deceased daughter. What follows is a descent down a rabbit hole of faith, doubt and precognition, which tests the limits of Sutherland’s character’s sanity in particular. Highly atmospheric, and making spectacular use of the natural canals and bridges of Venice, Don’t Look Now winds through dark streets both visually and symbolically in search of answers to its burning questions. Famous in its time for a fairly explicit sex scene that has long since been surpassed by modern cinema, Don’t Look Now instead deserves to be remembered for its performance by Sutherland as the truth-seeking father, which slowly ramps up into a conclusion that will haunt your nightmares. If ever I have beseeched you to not spoil a film’s ending, it is now. —Jim Vorel