What The Birdcage‘s Grand Gay Comedy Tells Us about Family 25 Years Later

Director Mike Nichols’ The Birdcage (1996) holds up extraordinarily well 25 years later, even as so much of how queer people are portrayed in the media has shifted drastically. Elaine May’s screenplay is hilarious and filled with genuine moments of heart, and Robin Williams and Nathan Lane are pitch perfect in their roles. The movie itself is a warm hug of queer comedy, diving unabashedly into South Beach culture and the flashy lives of ‘90s Floridian gay showbiz. But one aspect that makes the film such an interesting time capsule of the era is its depiction of family.

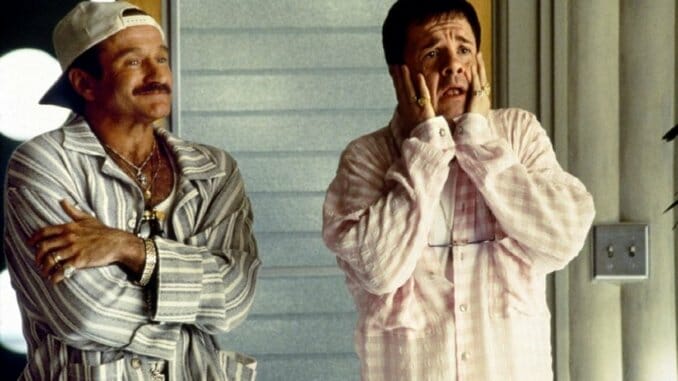

For those who haven’t seen it, The Birdcage tells the story of nightclub owner Armand Goldman (Robin Williams) and his partner Albert (Nathan Lane). When Armand’s son Val (Dan Futterman) comes back from college announcing that he’s going to get married to Barbara Keeley (Calista Flockhart), the daughter of the ultra-conservative Senator and Mrs. Keeley (Gene Hackman and Dianne Wiest), the Goldmans must turn their lives upside-down to make dinner with the future in-laws into a smashing success.

Cue the laughs as the Goldman house is transformed from gay art paradise to Catholic severity. A bevy of gay men stream through the door, whisking away nude art and replacing it with crucifixes and stacks of aged Nancy Drew books. While the house is easy to “straighten up,” Armand’s partner Albert is…less so.

The first solution proposed by Val is just to get rid of Albert for the evening. But after Albert’s feelings are understandably hurt, Armand attempts to coach him into straightness—urging him to butter toast “like a man” and to walk like John Wayne—but none of it really works. During the film’s most heartbreaking scene, Albert, who normally dresses in pastel shirts and silk scarves, presents himself to Val and Armand wearing a plain black suit and dress shoes. He walks into the room slowly and unsteadily, trying his best to project a certain form of acceptable manliness: “I took off all my rings. I’m not wearing any makeup. I’m just…a guy.” In response to this, he’s chided for wearing pink socks (as if pink socks are some sort of glaring signifier for queerness). It’s devastating because, while part of this farce is about the Keeleys, the people who are actually doing this to him are his loved ones.

Hijinks are always fun, but the fact that these hijinks happen just so Albert can “earn” the common courtesy of eating dinner with Val’s future in-laws casts a bit of a dark cloud. Throughout The Birdcage, Albert is constantly being treated as an outsider in his own family, both by his partner and by the boy he helped raise. Of course, Armand pushes back against Val’s attempt to banish all queerness from the house, but never in front of Albert. Plans are made behind his back, and Armand and Val function as a team working to fix the “problem” of Albert’s visible queerness.

For anyone who’s ever heard “We thought it’d be better if you weren’t here” or “It’s just for tonight,” the things that Armand and Val say to Albert are shattering. And they do seem to crush Albert, as he responds, “I understand. It’s just when people are here.” The film sets up the ultra-conservative Keeleys as the antagonists, but doesn’t quite acknowledge exactly what Val’s (and later, Armand’s) callousness could mean to Albert, who—after being told again and again that he shouldn’t be around for the dinner—declares “I don’t want to stay where I’m not wanted, where I can be thrown out on a whim without legal rights” and leaves. This statement also brings up the issue that Albert doesn’t really have a defined role in this family dynamic. Armand is Val’s father. Albert and Armand aren’t (couldn’t have been) legally married.

It’s a moment that specifically speaks to queer life at a time when same-sex marriage (as well as same-sex activity in Florida) was illegal. It speaks to the reality of lifelong partners not being able to visit each other in the emergency room and not having legal rights to shared property.

In another movie, one could imagine the scene as the plot’s push for an engagement or a reason to have children and settle down—to get to that next step in the relationship, whatever it may be. But the relationship between Armand and Albert in The Birdcage is already fully mature. They’re not young men trying to define themselves. They’ve been together for years. So when Armand hands Albert palimony papers to sign, it doesn’t feel like a movement forward as much as an acknowledgment of what’s already there. A naming. The scene, played quietly at a bus stop as a large ship passes behind them, reminds us that love isn’t just romantic declarations. It’s also sharing a life day to day and facing the insecurities that come up when a wrench gets thrown in the works. The scene reminds us what it means to be told that we’re loved, especially when circumstances are trying to obscure that love—if only for one night.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-