The Fugitive and Dead Wife Cinema

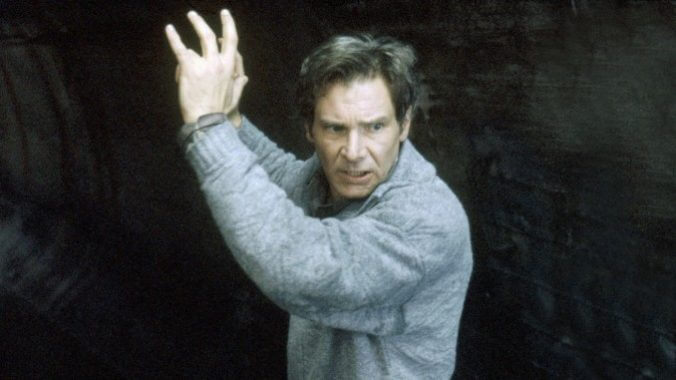

Richard Kimble (Harrison Ford) didn’t kill his wife (Sela Ward), although it sure looks like it. After the vascular surgeon’s wife was killed in their home, he gets framed for murder—but on his way to death row he flees from justice and sets out to prove his innocence. That is, if he can escape the long arm of the law attached to Deputy U.S. Marshal Sam Gerard (Tommy Lee Jones), who makes it clear when he corners Kimble at the lip of a monumental dam that he doesn’t care about Kimble’s innocence, he just needs to bring him in. Kimble, of course, turns into an obvious dummy to escape. Sterling stuff.

For 30 years, The Fugitive has remained one of the best ‘90s thrillers, from a decade when Hollywood perfected the formula for making exciting, flashy suspense films efficiently and effectively. The whole family wanted to see Ashley Judd get revenge on her husband, or Clint Eastwood try to stop a presidential assassination, or Richard Gere accidentally acquit a psychopath. But with a trend of bankable stories come repeated tropes and archetypes, and The Fugitive enshrines one that has haunted the thriller genre for decades: The dead wife. When Kimble’s wife Helen gets slain in the opening moments, we are reminded of the designated role for women in crime and espionage films. They are there to motivate and complexify our male hero (Ashley Judd doubly jeopardizing herself notwithstanding) and if they can do that without even having to be alive, all the better.

In movies, a murdered spouse is so appealing because it’s a deeply personal crime while also being universally regarded as terrible by audiences worldwide. Desecrating such a traditional staple of heteronormative society lets a screenwriter justify any action or behavior in their characters; after all, you can just write it so that your character loves his wife more than anyone has ever loved their wife, which is why they’re driven to the increasingly implausible ends of an action hero.

The canon of bog-standard, uncomplicated movies where the death of a wife motivates the entirety of our widower’s actions are plentiful: Memento, Mad Max, Unforgiven, John Wick, The Frighteners, The Revenant, Up, Shutter Island, Looper, The Road and Gladiator are only a small selection. Via shorthand, complexity and emotional nuance are pushed onto our character and their journey; if the wife is dead, a screenwriter can get away with only penning one side of a fully-formed relationship, and also doesn’t have to feature too many of those pesky women that screenwriters hate to write.

You could even make the argument that a dead wife thriller satisfies a male fantasy: Your life is transformed into feats of pursuit and daring-do with a morally pure motive, all while you’ve been freed from the stereotypical shackles of matrimony. Wives aren’t dames; they’re not sexually available and exciting women, but represent stability and the status quo, and their death is the perfect way to throw our character’s life into chaos.

The Fugitive’s classic thriller trappings (dead wife included) trace back to the ‘60s TV show it’s based on, a medium that was stepping up its game as the film studio system was crumbling, and which looked to the preceding decades of noir and Westerns for their escapist fare. These genres had solidified the male hard-boiled hero as an isolated, lonely and usually lightly misogynist figure. These men weren’t widows, but confirmed bachelors; the wife’s role in suspense films was usually found in films not focusing on men, like Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca. Here, the lingering imprint of a widower’s first wife haunts her much younger successor, the crown jewel in a subgenre best described as, “Help, I’m Being Haunted By My Dead Wife.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-