Time Capsule: Milk ‘N’ Cookies, Milk ‘N’ Cookies

Every Saturday, Paste will be revisiting albums that came out before the magazine was founded in 2002 and assessing their current cultural relevance. This week, we’re looking at a power pop record lost to the sands of time but resurrected through the styling of numerous rock anthropologists of the modern-day—songs made by a band that shared bills with Talking Heads, Ramones and Blondie, only to be a footnote in CBGB’s heyday.

Power pop is having a moment—not quite a renaissance, as the subgenre never really left in the first place, but a forward-momentum still galvanized by worthy successors. Thinking about contemporary artists—Hurry, 2nd Grade, Ducks Ltd.—making power and jangle pop, it’s hard not to get a bit smitten about the whole ordeal. I mean, hell, Nick Lowe just dropped a new record and it’s really good. Big Star just celebrated the 50th anniversary of Radio City; the band Alvvays exists because Teenage Fanclub paved a way for them; while the Badfingers, Cheap Tricks and Jellyfishes of the world aren’t often counted in the zeitgeist populace, their influence still reverberates. Even a half-a-century ago, as New York City was America’s bustling creative hub, the bands that were going national were acts like Blondie and the Ramones. They had crossover appeal but roots stationed in oldies (or oldies where they came from). In the CBGB era of the city’s rock pantheon, reverence falls onto the New York Dolls or Talking Heads. There is a band that was oft-forgotten in those conversations: Milk ‘N’ Cookies, a rag-tag bunch of suburbanites who coupled together to make the kind of rock music you can play for anyone anywhere—a band that shared bills with those aforementioned NYC greats.

Milk ‘N’ Cookies formed in 1973 after vocalist and guitarist Ian North met a guitarist by the name of Jay Weiss. Weiss would, out of necessity, pick up a bass and, in due time, he and North became collaborators who made a demo tape on a TEAC four-track. They called themselves Milk ‘N’ Cookies, playing an early gig where Justin Strauss shook a tambourine and sang back-up. Eventually, Strauss would assume lead singer duties from North—because Strauss’s command of the stage, even as a tambourine-playing set piece—captivated crowd-goers. A year later, Milk ‘N’ Cookies became a Long Island favorite, touring bars and school dances in town and, down the line, performing a gig with John Hewitt—the manager of Sparks—in attendance. Hewitt became Milk ‘N’ Cookies’ manager and hooked them up with producer Muff Winwood, who would only work with the band if North fired Weiss and replaced him with Sal Maida, who played in Roxy Music. “The guilt of that has weighed on my conscience ever since,” North later said about dismissing Weiss, his best friend, from the group.

The band eventually signed a deal with Island Records, releasing a single called “Little, Lost and Innocent” that failed to chart. Such a commercial flop left Island in the lurch; they had no clue how to market this band of riffing, melodic nobodies making noodly, crunchy pop rock bliss without a face to sell on the front of it. Island wanted North to stick with them, so they offered him a solo deal—which he took, forming a band called Ian’s Radio and seeing Maida quit Milk ‘N’ Cookies so he could play bass with Sparks. The Sex Pistols’ rise in popularity is said to have informed Island on how to sell Milk ‘N’ Cookies’ records, which meant marketing them everywhere as a “punk band”—and labeling their debut eponymous album as such, too. The glammy parts of Milk ‘N’ Cookies’ sound weren’t opportune enough for the overlording suits, so they ditched the Bowie of it all for a categorization a bit rougher around the edges—even though that categorization never fully fastened into place. It never really fit them.

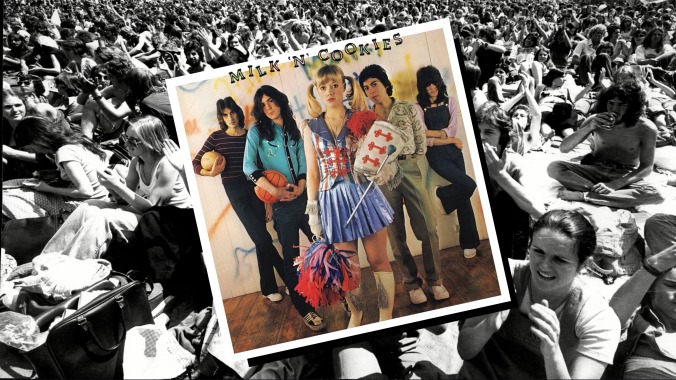

Listening to Milk ‘N’ Cookies is, by no means, a profound experience. It’s a record about sex, partying, being young and girls, girls, girls—the cover sports a cheerleader standing in the foreground with the band lingering behind her. But, even if North and the guys weren’t making songs that would challenge the curious ear, their schoolboy antics and Sweet-influenced sound is likely why the Feelies and the Apples in Stereo kick so much ass. Milk ‘N’ Cookies’ milieu was enough of a novelty to be worth selling in a somewhat provocative, coltish way. A band like the Lemon Twigs still take immediate influence from North and his peers—and that connection makes sense, as Captured Tracks reissued Milk ‘N’ Cookies eight years ago and, now, the Lemon Twigs are a part of that label’s roster.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-