Have Yourself a Very Beach Boys Christmas

60 years ago this winter, the Hawthorne legends recorded a holiday record in response to Phil Spector’s A Christmas Gift For You, setting the stage for Pet Sounds two years later.

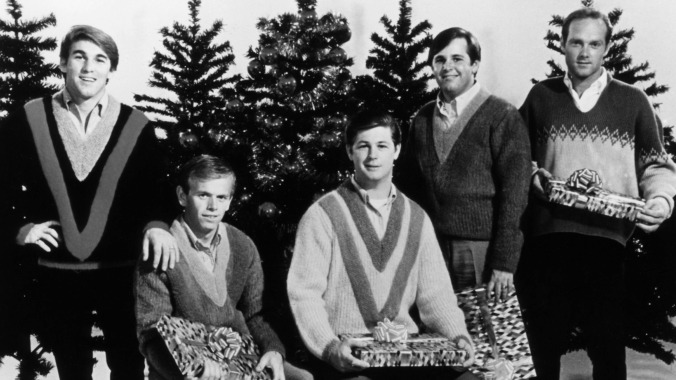

Photo by RB/Redferns

Between September and October 1963, 20 session musicians and four vocal acts decamped to Gold Star Studios in Hollywood to make a Christmas album with Phil Spector. Spector was a New York record producer who’d created the Wall of Sound—a Wagnerian diffusion of tone colors and opaque symphonic arrangements. It shaped the history of pop to come, positioning him as one of contemporary music’s first auteurs. He wasn’t a sensation or a prodigy by trade; his brilliance existed because he had total control over his artists’ recording sessions. His acclaim started in 1958, for his oversight on the Teddy Bears’ #1 single “To Know Him is to Love Him.” He was once an apprentice to Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, only to make a pivot and co-found Philles Records with Lester Sill at the age of 21. There, he was dubbed the “First Tycoon of Teen,” signed his first artist (The Crystals) and released the label’s first single (“There’s No Other (Like My Baby).”

Philles Records quickly established a roster of the Crystals, the Ronettes, Darlene Love and Bob B. Soxx & the Blue Jeans—a Hollywood contrast to Motown’s amalgam of Mary Wells, the Supremes, the Marvelettes and Martha and the Vandellas in Detroit. By then, Elvis had made a great Christmas album, as did Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole and Frank Sinatra. It was a mellow endeavor used to push record sales rather than create substantial art. Those aforementioned releases were good, but they felt like collages—because they were, as most projects lacked a structured identity in such a singles-dominated, chart-minded era of popular music. There’s a reason why Philles Records only put out 12 albums in its eight-year existence: There were rewards to reap in 45s.

When all of Spector’s artists made it to Gold Star, they were welcomed by his de facto house band, the Wrecking Crew, to make a Christmas record aptly titled A Christmas Gift for You from Philles Records. It became the first great collection of secular holiday standards (except for the Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry-penned “Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)”); it was a revue captured on wax, a baker’s dozen of the greatest holiday performances ever recorded. You’d be hard-pressed to find someone who doesn’t believe it’s the best Christmas album ever made. I’d even argue that it’s one of the best albums ever made, period. Thanks to his Wall of Sound, Spector turned the world’s greatest holiday into his own symphony through echo chamber reverb, maximalist ensembles and advents of formulaic combinations—instruments stacked on top of one another but indistinguishable to the untrained, average ear.

Whether it’s Darlene Love’s “Christmas (Baby Please Come Home),” or the Ronettes’ triplicate of “Frosty the Snowman,” “Sleigh Ride” and “I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus,” Philles Records had struck gold and Spector became the greatest producer of his generation. While the Wrecking Crew were recording the instrumental for the Crystals’ “Santa Claus is Coming to Town,” an awestruck, 21-year-old Brian Wilson attempted to contribute a piano piece to the song. Spector rejected it, though, because of poor playing—“substandard” is how the producer framed it. But A Christmas Gift For You quickly became Wilson’s all-time favorite record, just as the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby” was his favorite song of all time and inspired him to write what is, for my money, the greatest pop song ever captured on analog: “Don’t Worry Baby.”

Around the same time the Philles Records was making A Christmas Gift For You, the Beach Boys, who’d accumulated three consecutive Top 10 hits (“Surfin’ U.S.A.,” “Surfer Girl,” “Be True to Your School”), took to Western Studios on Sunset Boulevard to make their first-ever Christmas song: “Little Saint Nick.” Brian had known of Spector’s recording across town at Gold Star and felt inspired to make one of his own. “I wrote the lyrics to it while I was out on a date and then I rushed home to finish the music,” he said. Taking a note from the “Little Deuce Coupe” arrangement, the Beach Boys turned their hot rod hoopla into a cruise-worthy trip about Santa and his sleigh. It rocketed up Billboard’s seasonal weekly Christmas Singles chart, peaking at #3, and wedged its way into the Top 25 of the Hot 100 by the year’s end. It wouldn’t take long before Brian Wilson wanted to make his own A Christmas Gift For You.

Between January and June of 1964, the Beach Boys found major commercial success, thanks to “Fun, Fun, Fun” reaching #5 on the pop charts and “I Get Around” hitting #1. Shut Down Volume 2 found great success upon its release in March of that year and, just before its successor All Summer Long climbed into the Top 5 of the Billboard Top LPs chart, the band split time between Capitol and Western Studios recording what would become The Beach Boys’ Christmas Album and outtakes of “Little Honda” and “Don’t Hurt My Little Sister.” And the band’s chart reign would continue while they waited to put their holiday record on the shelves, releasing Top 10 hits “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” and “Dance, Dance, Dance” back to back in August and October, respectively.

Five of The Beach Boys’ Christmas Album’s 12 tracks were original compositions by Brian, all of which are included on side one. “Little Saint Nick” gets a proper album treatment, with overdubs of sleigh bells, celeste and glockenspiel added to the track’s mix on stereo pressings of the record. “The Man with All the Toys,” “Santa’s Beard,” “Merry Christmas, Baby,” were featured after—all of which are sung or co-sung by Mike Love. On “Christmas Day,” Al Jardine sings lead for the first time ever. Brian took what he knew from Spector and challenged the sound barrier by doubling up on basses, tripling up on keyboards and making “everything sound bigger and deeper.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-