40 Years of Swordfishtrombones: How Tom Waits Broke His Own Mold

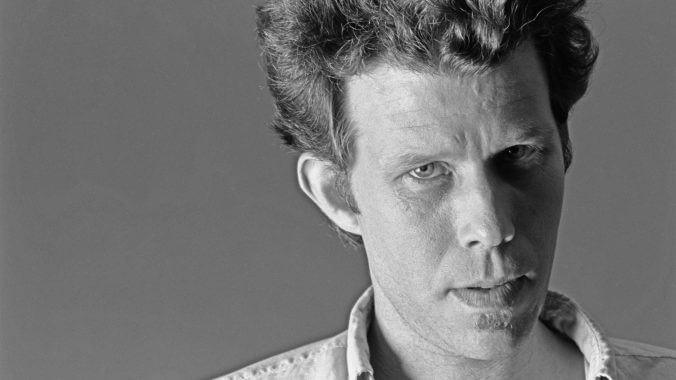

Photo by Lynn Goldsmith/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Tom Waits contains multitudes. That statement will come as no surprise to anyone who has ever laid down small change for one of his records or caught one of his enigmatic late-night appearances. He’s spent a cup of coffee as a San Diego folkie, moonlit as an inebriated lounge act and scrapped and salvaged as a beatboxing junkman. He’s served as a cinematic muse to auteurs like Francis Ford Coppola, Terry Gilliam and Jim Jarmusch; perched as a songbird in the ear of everyone from Bette Midler and Rod Stewart to Tori Amos and Scarlett Johansson. There was also a sea shanty with Keith Richards in there somewhere, for those keeping score at home. It’s not the typical rap sheet for the son of middle-class school teachers from a small burg outside of Los Angeles.

Perhaps, most surprising then is that Waits’ eclectic career somehow seems to make sense when looking back across the scope of five-plus decades in the music business. His evolution has been less a series of seismic shifts or sea changes between albums (and personas) and more akin to a subtle set of permutations of what came prior—mixed with elements of where the artist had set his sights next. Consequently, Tom Waits never sounds quite the same way twice—and yet, he always still registers unmistakably as Tom Waits. And it would be just that simple if not for 1983’s Swordfishtrombones, the punctuating, head-scratching, nightmarish outlier of a record that turned everything listeners thought they knew about Tom Waits the artist on its confetti-covered head. Now, 40 years later, Swordfishtrombones boldly hangs mounted within Waits’ discography as the departure point for his transformation into the experimental tunesmith and avant-garde performer fans recognize and revere today.

By the early 1980s, Waits had settled into a comfortable niche on the Asylum label. He’d already made a half-dozen albums alongside producer Bones Howe, exploring every corner, ashtray and toilet you might find in a jazz club or its alley out back. Those collaborations included Small Change, one of the funniest and most brutally poignant musical meditations ever on life once the bottle starts gaining on you. But those songs and the lifestyle that fermented them had worn thin for Waits. He sounded bored to gin-soaked tears on One from the Heart, the 1982 Oscar-nominated soundtrack he composed and recorded with Crystal Gayle for friend and director Francis Ford Coppola. It’s an affair as watered down as a cheap drink left melting all night on a hot barroom jukebox and flickers like a neon sign telling Waits that, creatively speaking, this might have been last call and near closing time for his current act.

Waits amicably parted ways with Howe following One from the Heart. More importantly, he had met future wife and longtime collaborator Kathleen Brennan on the film’s set. Waits has credited Brennan several times over the years as the force who nudged him towards the next (and his most definitive) creative harvest. He once, jokingly, told David Letterman that Brennan is the “broad” that “broadened” his songwriting. Today, fans know her as a co-writer and co-producer across several of Waits’ most beloved projects. Among her earliest influences on Waits, she turned him on to the madcap music of Captain Beefheart, whose strange imprint can be found all over the experimental compositions and vocal stylings of Swordfishtrombones. With Brennan now in his creative corner, Waits was on the brink of taking a sledgehammer (or at least a marimba mallet) to both the guise and persona he had spent nearly 10 years slowly building a successful career upon.

Swordfishtrombones often gets counted as the one that got away from Asylum; more accurately, though, the record label threw it back—and it’s hard to blame them. Gone was the familiar, raspy jazz crooning; gone were the saxophones and Waits’ signature piano fare. And maybe most damningly, there was a stark absence of the romantic, Kerouacian language of Waits sharing a bottle from a paper bag and dragging listeners through his usual late-night haunts. The first two minutes of the album (“Underground”) sound nothing like an Asylum Tom Waits record. The song sinisterly slouches along to plodding bass marimba and a baritone horn, as Waits barks (or belches) about a shadow world tethered beneath us. This is not a search for the heart of Saturday night—to say the very least. It’s dark, abrasive and unnerving, and that’s just the initial descent into the belly of Swordfishtrombones. When Asylum declined to put out such an anomalous album, Island Records brought Waits aboard and began a decade-long partnership that would, largely, come to define the artist for future generations of listeners.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-