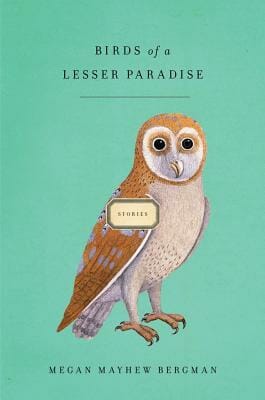

Birds of A Lesser Paradise by Megan Mayhew Bergman

What Makes A Southern Writer?

The South has always considered itself a storytelling nation—an independent and misunderstood country of citizens who balk at belonging, cling to unity and narrate the difference. We have always known this fact: The shortest distance between two opposing forces is a good story.

Every now and then, the outside world takes notice of this technique of ours, which is not one of rationalizing, but rather a conjuring of justice. Right now happens to be one of those times, it seems: Southern is trendy.

Blame the economy, the president or the weather, but people seem increasingly to search for either solutions or solace in the South. Take the keen inquisitiveness of Kentucky-born John Jeremiah Sullivan’s essay collection, Pulphead. Its connecting theme is his quest to understand and belong to his adopted region, the deeper South. (I cannot recommend highly enough his essay “Mister Lytle,” about the last days of Andrew Lytle, Sullivan’s eccentric mentor at Sewanee: The University of the South. It is a heart-stopping, knee-weakening feat of stunning Tolstoyian magnanimity.) Karen Russell’s Florida-set Swamplandia! flies off the shelves at upscale clothing stores like Anthropologie. Even the hillbilly noir of McSweeney’s author John Brandon has taken off, when perhaps in a more stable national mood, it might not. Readers crave the fantastic, perverse sadness of Southern writing. They’re on it like a duck on a June bug, as my Alabama-born grandfather would say.

Still … just how much of the label “Southern” requires earning? Is it simply an accident of geography? Not all writers from the South claim the label, just as we have examples of outsiders, like Sullivan, who write of nothing else. A few themes prevail in traditional Southern writers and in the new ones—violence, family, nature, God—but they do not veer too far from the stuff of life. The difference is in attitude, in an idiosyncratic logic: Southern writers, different from Northern or Western or just plain American, go forward in nature rather than just with it.

But here’s a challenge. I recently came across a collection with writing on the South that tiptoes so elegantly and softly over the old themes that I began to think differently about the whole category of Southern writing.

Megan Mayhew Berman’s debut collection of stories, Birds of A Lesser Paradise, deals mainly in nature and with a woman’s role in today’s South. Her writing shines when linking nature and not just womanhood, but femininity.

Think of antonyms for the word magical—boring, dull, plain, unmysterious, apparent. Perhaps the intersection of these opposites is where superstition is born. What one simply brushes off as dark or eerie in typical Southern writing falls right about there in this spectrum, and Bergman excels at a mundane kind of gothic that is both familiar and frightening.

Though a resident of Vermont, Bergman will be pegged from here on out as a Southern writer for the following reasons:

•She grew up in North Carolina.

•The best stories in the collection take place in the South.

•These stories prove strange and sad.

Eudora Welty claimed Chekhov as “one of us”—a Southern writer. In 1972 she told The Paris Review, “He loved the singularity in people, the individuality. He took for granted the sense of family. He had the sense of fate overtaking a way of life, and his Russian humor seems to me kin to the humor of a Southerner. It’s the kind that lies mostly in character. You know, in Uncle Vanya and The Cherry Orchard, how people are always gathered together and talking and talking, no one’s really listening…Yet there’s a great love and understanding that prevails through it, and a knowledge and acceptance of each other’s idiosyncrasies, a tolerance of them, and also an acute enjoyment of the dramatic.”

Here are three other reasons Bergman should be touted as a Southern writer:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-