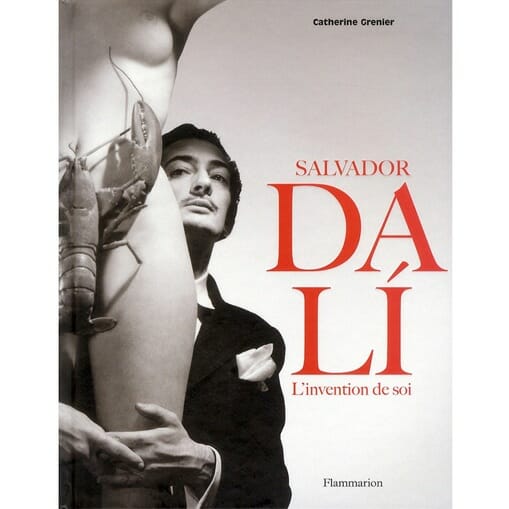

Salvador Dalí: The Making of An Artist by Catherine Grenier

Hello, Dalí

“The master told me I had to subject myself to reality and that only later could one let oneself go. His idea was that one had to deal with the ugly first and then the beautiful. I took the firm resolution to follow this academic teaching with all my heart.”-Salvador Dalí, age 16

A most peculiar man.

If our age may be characterized by a fascination with the outsized personality, the shameless shaman-showman, then Dalí is the prototype. His expansive and persistent influence on contemporary art and culture remains obvious, and it is through his dark and unsavory peculiarities that we often see ourselves in his work.

Catherine Grenier’s excellent reappraisal does not attempt an exhaustive study of the artist; instead, she takes a new look at his work and personality, closely analyzing the interplay between them, to examine what the Dalí myth teaches us about present-day issues and desires.

Grenier, currently Deputy Director of the National Museum of Modern Art at the Centre Pompidou, approaches Dalí from her background as a curator and art historian. Tracing Dalí’s artistic development chronologically through successive periods of work, she parses her analysis into bite-sized essays on the various artistic, scientific and philosophical influences that, together with Dalí‘s innate brilliance and extensive eccentricity, formed a colossus of contemporary culture.

Supremely confident of his gifts, Dalí arrived at art school in Madrid at 18. He promptly set out to invent himself as the great artist fate meant for him to become. Grenier describes the evolution of his early style, as he commenced the process of turning his life into his art:

As soon as he arrived as a student in Madrid, he strove to make his public front coincide with the artistic front he was intent on presenting to his friends. It passed through several metamorphoses, each with its own costume and corresponding character traits. The shaggy Bohemian, the trendy painter — the slick-haired dandy — and the tango dancer. After meeting [Andre] Breton, the persona he composed was that of an “exotic society painter,” a figure that fitted in with what he thought the surrealists expected of him. Later on, two telltale signs of his status as unconventional appeared: his stylized Spanish costumes and his mustache, which would evolve from a discreet Errol Flynn pencil into the “radar mustache” of his final period.

In the same way, he invented his own way of talking, with an outrageous accent and pronunciation. In public, his French was almost incomprehensible, while he had actually mastered the language in early childhood. His writings transform a tendency to dyslexia into idiomatic and erratic spelling, and a style that teems with malapropisms and neologisms, all perfectly untranslatable. His artistic self thus invaded every territory in which a personality might be expressed: appearance, attitude, behavior, character, language and speech. Honed and oiled, the Dalí myth formed the cornerstone of his genius: a work of art that incorporated all the others. After Duchamp, he was the first artist who – without ceasing to create – turned his whole life into a work of art.

Through his life, all was in service to his art, all in outrageous service to Dalí. His intellectual curiosity seems profound—interests in psychoanalysis, Einstein’s theories of relativity, the complexities of the double helix and even catastrophe theory course through his art and life. But, more than anything else, his meticulous eye for the disquieting detail and the preternatural composition … along with the painterly skills he applied to classical forms … draw the viewer’s eye to his canvases.

While Grenier’s appreciation for her subject is evident, she remains objective. Noting the sharp divide among critics even early in Dalí’s career, she observes:

Lauding his talent and technical mastery, several commentators nonetheless reproached his works for being intellectual and cold. Such assessment seems astonishing in light of the subject treated, for the most part sensitive evocations of familiar, often intimatist scenes. The remark is understandable in the context of two of the painter’s more salient characteristics: a flexible attitude to style that shuttled between radically opposed types of representation, and the application of constructed form to elements on the living world – waves or the human figure – which he attempted, according to his own terms, to ‘crystallize’.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-