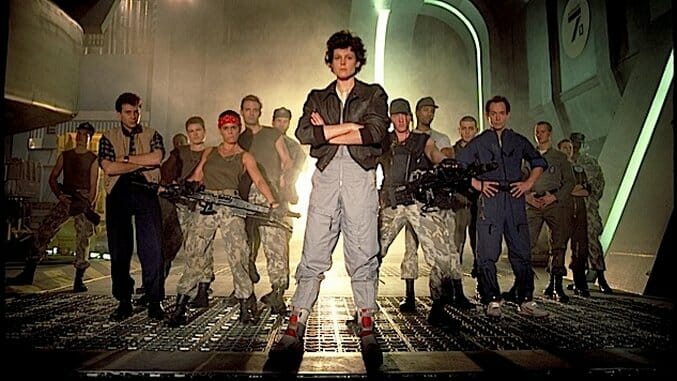

On Flamethrowers, Corporate Greed and Acid Blood: Aliens Turns 30

By the time July rolled around in 1986, moviegoers that year had already been treated to the awe and wonder of hitchhiker cautionary tales, Molly Ringwald’s reprised role as sad teenager (who’s poor this time!), two animated films about robots that can transform into less cool things than robots, Sly Stallone vs. an axe-clanging cult, Goose’s faulty “Eject Seat” button, Matthew Broderick as a lying, uneducated rich kid, and David Bowie’s scandalous elf king britches. Memorable films aside, 1986 deserves four-stars for at least diversifying its weird shit (robot identity crises notwithstanding) as opposed to churning out 50 variations of Will Ferrell screaming or that one rom-com where the unlikely couple defies the odds.

Then came Aliens. Released seven years after Ridley Scott’s groundbreaking, peed pants-inducing original film, Aliens answered the (probably) pressing question of could it get much worse than being stuck on a spaceship with just one xenomorph and a milk-filled android played by pre-Bilbo Baggins Ian Holm. As it turns out, yes. It could absolutely be worse. Long before denying a more buoyant wooden door for Leonardo DiCaprio or creating two-and-a-half hour long environmentalism infomercials featuring affable blue aliens who talk to trees, James Cameron accomplished the nearly impossible task of creating a science fiction sequel not named Star Wars that could hold its own against the enormous standards set by its predecessor.

Having read his screenplay for The Terminator and probably unaware of his involvement with Piranha II: The Spawning, Brandywine Productions approached the then-29-year-old Cameron about writing a sequel to Alien. Being the robot/alien/explosions-loving writer he is, Cameron jumped at the chance and the rest is movie history. Aliens saw Cameron take the risk of continuing an otherwise open-and-shut sci-fi horror narrative, instead of going the safer route of simply telling a separate but similar story of a blue-collar salvage crew getting their asses handed to them by the slobbering, two-mouthed, acid-blooded offspring of H.R. Giger.

Revisiting the “that’s that” denouement of the original film would naturally run the risk of not leaving well enough alone and end up functioning as little less than an unnecessary footnote. But Cameron didn’t simply revisit the final scene of Alien. He uses it as the opening scene for the sequel and not as a recap a la Rocky. Beginning with Sigourney Weaver’s Lt. Ripley and her fearless cat, Jonesy, sleeping in the cryochamber onboard the escape pod they’d used to escape the self-destructing Nostromo, Aliens jumps right in and doesn’t look back. It’s the only time in the film that you really think about what came before, and it’s ultimately the last glimpse of a still relatively hopeful Lt. Ripley.

From there, the film cultivates its own kind of palpable fear and one that’s inherently different from the isolation of the original film. Mistrust of authority or the ruling class are familiar themes for Cameron. In fact, it’s not far-fetched to suggest that much of why his films have been so successful falls squarely on Cameron’s ability to place believable characters in unbelievable circumstances against a variety of opposing and generally corrupt forces that run the gamut of setting from post-apocalyptic to historical to science fiction at its most terrifying. To that end, Aliens capitalizes on what was a briefly mentioned but no less unsettling suggestion from its predecessor.

Of the first film’s many blood-curdling scenes, perhaps the most chilling and relatable to audiences is the confrontation between Ash and Lt. Ripley near the film’s climax. In what now seems an especially smart move by Scott, the film goes beyond what was already an outstanding dynamic of science fiction and horror. Though a passing moment juxtaposed against the rest of the film, the scene ultimately sets the stage for a silent adversary that underscores virtually every aspect of the franchise from the sequel all the way through the well-meaning but ill-conceived Prometheus. Though technically called Weyland-Yutani, that opposing force is appropriately referred to throughout the films simply as “The Company.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-