Define Frenzy: Asian Queerness

“Define Frenzy” is a series of weekly essays for Pride Month attempting to explore new queer readings or underseen queer films as a way to show the expansiveness of what queerness can be on screen. You can read last year’s essays here and last week’s essay here.

My friend, critic and writer Inkoo Kang, and I have a running joke-cum-debate.

Since the show premiered in 2005, I believe, with my raisin-sized heart, that the middle child of the Huang family on ABC’s Fresh Off the Boat, who goes by the name of Emery (Forrest Wheeler), is queer—at the very least potentially. Inkoo believes I am the only one who thinks this, and disagrees, reasonably so. She and I both know that Asian American presentations of masculinity don’t fit within conventional white American presentations and performances of masculinity, and thus are often read as queer, or at the very least, sexless. This is aided and abetted by the long history of the emasculating of Asian American men in the United States, often utilizing Asian male characters in film and TV as comic eunuchs, totally devoid of interiority (nevermind a sense of their own eroticism). I like to read Emery as being part of a lineage of the profound experiences and stories of queer Asian men, partially because there are so few of them that aren’t half-assed jokes or barely written punch lines. What we have, though, can be humane and beautiful and complex, like the characters that lead Hong Kong director Wong Kar-Wai’s Happy Together (1997) and American director Andrew Ahn’s Spa Night (2016), both films that deal with queer sexuality within an Asian and Asian-American context.

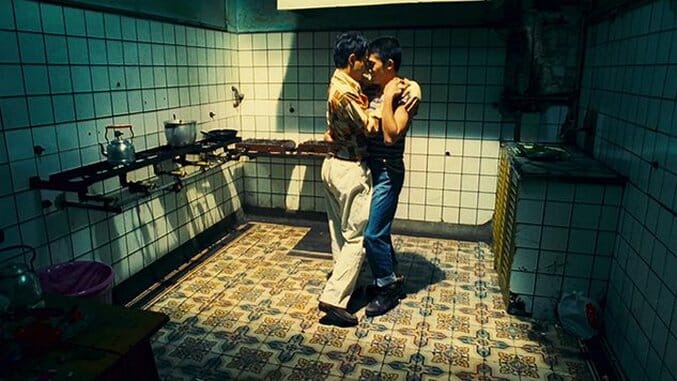

Wong Kar-Wai makes films that are like memories printed on ribbon, imbuing his works with a textural elasticity that dances in the wind, or can slow down time. In the Mood for Love is the only way I like to get drunk, but Happy Together can even supersede that film with its empathy and detailed characters. Somewhat improvised, the film explores the tempestuous relationship of Ho Po-wing (Leslie Cheung) and Lai Yiu-fai (Tony Leung), whose move to Argentina from Hong Kong acts as a desire to fix the broken relationship that both men still care deeply about but nonetheless struggle to navigate. They are abusive to one another, self-destructive, and their relocation does nothing to repair the damage in the relationship. But, through Leung’s thoughtful, sensitive voice over, it’s clear how indelible the touch, sound and experience of and with Ho has been to him. For these men, they are able to unearth, forcibly and otherwise, the rawness in both themselves and the other. The English transliteration of the film’s original Mandarin title is “Exposed skin together.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-