Antlers‘ Clumsy Metaphors Cannibalize Its Scares

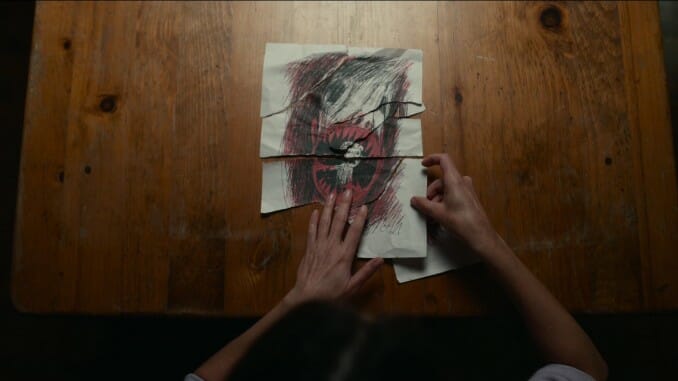

The first teaser for Scott Cooper’s Antlers dropped a full two years ago, back when Searchlight Pictures was still owned by Fox. You can watch the teaser on YouTube and see the Fox Searchlight logo pop up at the beginning, like a cursed artifact from the past. The scant teaser, under two minutes, played a scene from the film where Lucas (Jeremy T. Thomas), a troubled kid in small-town Oregon, reads a disturbing short story he wrote for his class. His teacher, Julia (Keri Russell), looks on with concern at the nervous, wizened child, while a threadbare piano tune ramps up with escalating intensity. Lucas’s voice carries on over an ambiguous collage of shots from the film that become more and more disturbing. From the teaser, it was near-impossible to piece together what the film was going to be about. At the time, it had felt like a strong indicator of what was to come. The trailer is vague and deeply unnerving, and no matter how many times I was forced to watch it in the two years since COVID-19 pushed Antlers’ official release date, it always chilled me.

Directed by Cooper (Out of the Furnace, Hostile), co-penned by Nick Antosca—whose short story, “The Quiet Boy,” the film is adapted from—and boasting an executive producing credit from Guillermo del Toro, Antlers is far from the film I felt the teaser promise. It’s something that became clearer over the past year, as the teaser gave way to full trailers, where additional plot details were added and the mythic creature, the Wendigo, was name-dropped. It’s my own fault for putting so much naïve stock in a film promo meant to generate interest by being as abstractly unsettling as possible. But when it comes to recent horror films, I am so frequently disappointed that I will happily latch onto anything that purports a welcome change from the same self-serious, ham-fisted metaphors that tend to populate the modern genre output. And what’s that saying? “Fool me once…?”

Julia Meadows is a recovering alcoholic, who recently traded her life in sunny California for her backwoods, rural hometown in Oregon not long after the death of her father. Russell carries Julia with the invisible weight of the abuse survivor that she is, her violent memories triggered by something as simple as a seat at her family’s old piano. She takes a teaching job at the local elementary school and reconnects with her sheriff brother, Paul (Jesse Plemons), who is fatigued by the evictions he has to implement on the impoverished locals. Now living together under the roof of their childhood home, tension prickles between the two estranged siblings due to the circumstances of Julia’s initial departure over 20 years ago. Nowadays, their town struggles with unemployment as a direct result of the opioid crisis, so prevalent that children absent from school are shrugged off by school administrators. As we later learn, it’s not uncommon that kids become suddenly homeschooled so that they can help push drugs for their parents, and so that their teachers can’t smell the meth on their clothes and feel compelled to contact authorities.

One such child of an addict is Lucas Weaver—an anxious boy and small for his age, he keeps to himself yet is bullied, nonetheless. Lucas’s father, Frank (Scott Haze) has become somewhat notorious to Paul, frequently necessitating an administration of Narcan from the weary sheriff in order to bring him back from the brink of yet another overdose. Despite the fact that Lucas’s mother has been deceased for some time, and his father is clearly an unfit parent, loopholes and an indifferent eye have allowed Lucas and his younger brother, Aiden (Sawyer Jones), to remain under Frank’s sole care. But three weeks ago, something happened to Frank while stopping by his worksite in the mines with little Aiden in tow. Three weeks later, Lucas now harbors a secret in his ramshackle home on the hill—a secret with an insatiable hunger only for food that bleeds.

Actor Jeremy T. Thomas’s unconventional features give him a naturally uncanny look, making him concurrently sympathetic and suspicious. Why does Lucas not contact the police? Why does he not save himself? But Lucas’s mistrust in other adults and the authorities makes sense from the perspective of a child whose family has already been ravaged enough by drugs and death. He doesn’t want to lose more than he already has. From her own experiences, Julia recognizes Lucas’s behavior as that of an abuse victim. She takes a sudden interest in piecing together what exactly is going on in the child’s home life, just as Paul, accompanied by officer Dan Lecroy (Rory Cochrane) and former sheriff Warren Stokes (Graham Greene), begins investigating a string of grisly murders in which bodies are flayed of flesh and torsos are ripped from their lower halves.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-