Ho Ho, Oh No: A History of Cinematic Killer Santa Clauses

In the fall of 1984, angry crowds milled and congregated at malls and theaters of the Midwest and East Coast, shouting holiday slogans and generally carrying on in a won’t-somebody-please-think-of-the-children manner. The target of the picketers’ ire was a new horror movie hitting theaters–and remarkably, it wasn’t Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street, which opened literally the same day, on Nov. 9, 1984. No, it wasn’t newly minted slasher icon Freddy Krueger who had whipped those puritanical parents and PTA members into a frenzy–it was the threat that a new film had dared to besmirch the good name of Santa Claus and the Christmas season by placing a bloody axe into the jolly old elf’s hands. The film was Silent Night, Deadly Night, and the protests were no small thing–within a week of release, the carol-singing picketers succeeded in first getting the film’s advertising campaign pulled from the air, and then the film pulled from theaters entirely by distributor Tri-Star Pictures. Other commenters quickly piled on. An incensed Siskel and Ebert rebuked the film’s very existence on air. Newspaper editorials railed on the death of the traditional American holiday, with Variety writing that “the depiction of a killer in a Santa Claus suit would traumatize children and undermine their traditional trust in Santa Claus.” All because this zero-budget little slasher flick, made for less than $1 million, had dared to embrace what has long since become a frequently reappearing horror cliche: A killer Santa.

The grand irony, of course, when it comes to the moral panic that thronged around the release of Silent Night, Deadly Night, was that it was by no means the first movie to feature a killer Santa Claus. It wasn’t even the first feature to be based entirely around the concept! Several others had come and gone from theaters in the decade before, attracting no particular attention or backlash. Prior to its release, producers of the film weren’t even particularly concerned about protestors keying on some kind of killer Santa controversy–they were instead afraid that the film’s depiction of Catholicism might bring out the angry zealots. Rather, it was the war-on-Christmas types who took offense, making Silent Night, Deadly Night a victim of its own provocatively effective marketing. Images that had been intended to attract genre weirdos–most famously Santa’s arm clutching an axe, descending a chimney in the theatrical poster–inadvertently called down the wrath of Middle America in all its emotionally stunted fury.

Looking back on the hysteria, though, I had to wonder: How much further back does the now stock trope of the killer Santa Claus go? Who was the first to dare to place a deadly implement in the cheerful, fat man’s hands? And why did those earlier instances pass without notice, when Silent Night, Deadly Night attracted so many headlines and angry superlatives? Join us, for a little journey into the dark underbelly of the American holiday (and horror film) season.

Santa Punishes the Naughty

Our modern conception of the character of Santa Claus goes decidedly easy on what through most of his history, was one of his core functions: Not just lauding kids with gifts, but actively taking a role in rooting out and punishing the wicked or naughty among us. This historical truth has always contributed a dark side to Santa, although it’s putting the cart before the horse to even refer to the character as “Santa” when that term is really only the modernized nickname for the general archetype of the Christmas gift-giver, a type of figure that exists almost universally throughout European folklore and beyond. “Santa Claus” as we know him is like an amalgamation of these many other, older characters–the English Father Christmas, Christian St. Nicholas, slavic Grandfather Frost, Dutch Sinterklaas and many others. The modern outline of what would become our own version of Santa Claus developed in the U.S. in the mid-1800s, particularly helped along by the illustrations of cartoonist Thomas Nast, who codified Santa’s appearance.

Today, even the idea that Santa would present a naughty child with a “lump of coal” instead of an Xbox feels like an almost entirely antiquated notion, not something we would dare to suggest in a society that attempts to protect (or coddle) the development of young children as much as possible. Gone are the collective warnings and threats toward kids that once pervaded the oral tradition–ominous stories of what would happen to bad kids if they didn’t behave, obviously meant to shape the behavior of the more gullible kids among us. Once upon a time, Santa Claus was depicted as meting out just as much punishment as he did seasonal joy, functioning as a Sword of Damocles hanging over their little heads–him, or his various wild and unruly helpers, characters such as Belsnickel or the now-embraced Krampus. Point is, that horror cinema didn’t need to invent the idea of a “scary” Santa Claus, because there had always been an element of danger to the character. If anything, the development of the Christmas horror genre simply rediscovered a part of the holiday that had been steadily repressed by our sanitized, Disneyfied society.

With that said, the arrival of a killer Santa in cinemas was pushing back against decades of cheery Hollywood precedent involving the character. Santa Claus had been appearing in American movies since more or less the advent of motion pictures–in 1909, the same year as the first feature-length American film (Les Misérables), director D. W. Griffith (of Birth of a Nation infamy) filmed a short called “A Trap for Santa Claus,” which involved a group of children laying in wait for Kris Kringle in order to capture him as he descended their chimney. Decades of similarly lighthearted entertainment would go a long way in crystalizing the American portrait of the universally good and loving version of Santa. Nor would a diversion from the norm have been easy to get into a feature film in this era, thanks to the more strict enforcement of the Motion Picture Production Code (AKA the Hays Code) from 1934 until roughly the mid-1960s. An idea like “killer Santa” feels like exactly the sort of perversion of good-old-fashioned, Puritanical American norms that the Production Code was intended to prevent for more than three decades.

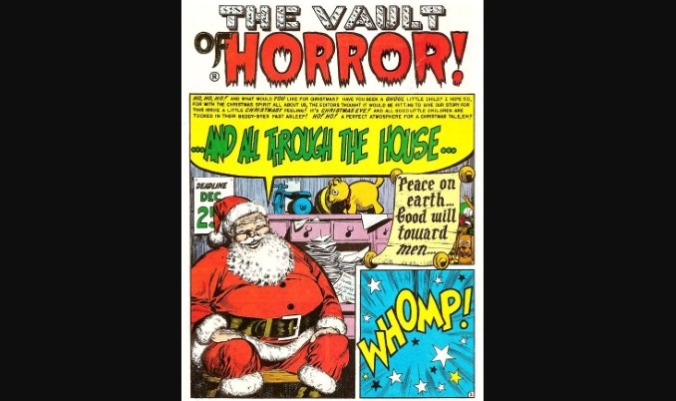

And it’s for exactly this reason that the advent of the killer Santa trope ended up coming not from the world of film at all, but from the scandalous world of 1950s American comic books. You could say that comic authors eased into the concept–pioneering cartoonist Will Eisner, for example, may have been the first to depict criminals dressing as Santa Claus as a disguise for their crimes in his comic The Spirit. This becomes the most common depiction of a renegade Santa in the era–a criminal or madman who happens to don the suit, rather than the literal gift-giver himself being depicted as a killer. The first undeniable “killer Santa,” meanwhile, likely arrived in the February 1954 publication of EC Comics classic Vault of Horror #35, and the story “…And All Through the House.” In it, a woman who has just murdered her husband on Christmas Eve is menaced by an escaped lunatic outside her home who happens to be dressed as Santa Claus. Unable to call the police for protection because of the abundant evidence of her own homicide, she fights to keep the house safe … until the ironic ending, when her young daughter lets the serial killer into the house because she mistakes him for the real Santa. Everybody dies, evil wins: classic EC Comics stuff.

Such a grim depiction of Santa was exactly the sort of thing that ultimately led to the formation of the infamous Comics Code Authority the same year, which would lead to the deaths of pioneering (and very risque) titles like Vault of Horror and Tales From the Crypt by 1955. With the comic book industry now being subjected to the same kind of censorship as the film world, further depictions of killer Santas would go into an extended hibernation, until the first real film depiction of a bloody-handed Santa would arrive in 1972’s … Tales From the Crypt? Yes, it’s true: 18 years after the publishing of “…And All Through the House” in comic form, the very same story was brought to the screen in the first cinematic adaptation of classic EC Comics horror stories, from British horror anthology specialists Amicus Productions. This is ground zero for the depiction of a killer Santa Claus on the big screen, again portrayed as a roving madman who stalks a woman and her child in their home, and arriving 12 years before the Silent Night, Deadly Night outcry. However, it’s only one segment of an overall anthology, which means that the first start-to-finish killer Santa movie was yet to come. Fun fact: “…And All Through the House” would go on to be remade yet again in 1989 as part of the Tales From the Crypt TV series.

Santa Claus in the Slasher Era

“Santy Claus only brings presents to them that’s been good all year. All the other ones, all the naughty ones, he punishes! What about you, boy? You been good all year? You see Santa Claus tonight, you better run boy, you better run for ya life!” – Silent Night, Deadly Night

As far as I can tell, there are no more direct cinematic examples of the killer Santa Claus until 1980, although the 1970s are notable for the proliferation and mainstreaming of other Christmas-adjacent horror films. Whoever Slew Auntie Roo? is an early example, also being a solid entry in the “psycho biddy” subgenre, while the confusingly familiar title of 1972’s Silent Night, Bloody Night (rather than Deadly Night) might understandably make one expect a killer Santa, but the proto-slasher actually has little to do with Christmas at all.

A footnote of particular interest is 1974’s foundational slasher Black Christmas, which absolutely is connected intimately with the holiday, but never features anything remotely close to a killer Santa Claus. That hasn’t stopped misinformation from proliferating online, however–in the course of writing this piece I encountered several instances of articles on Christmas horror asserting that Black Christmas actually has a killer Santa Claus in it, despite the fact that it absolutely does not. Is this just an instance of multiple writers misremembering or hastily assembling their pieces, or the result of crappy A.I. sowing misinformation among those attempting to use Google for research? Either way, it’s disconcerting to see these kinds of inaccuracies get any kind of foothold. Let’s set the record straight on the all-important topic of killer Santas.

The next genuine killer Santa graced the silver screen in what is arguably the most overlooked, low-profile film to be mentioned here: 1980’s To All a Goodnight, which seems to be relatively obscure even among devoted slasher geeks. This is something of an oddity, because To All a Goodnight has an interesting historical footnote going for it: Released in January of 1980, it appears to hold the title of “first slasher movie of the 1980s,” kicking off a decade that would of course be rife with them. It concerns a group of horny–and this is an understatement–college students spending the holidays at a largely abandoned finishing school for girls, where they are stalked by a killer dressed as Santa. It has quite a bit in common with other slashers that would follow in the immediate future–including May’s Friday the 13th, with which it shares almost the same twist and motivation for its killer! This makes its low profile all the more fascinating to me–how odd is it that Friday the 13th would go on to be the film that most directly inspired the golden age slasher boom, when that same honor could theoretically have been bestowed on To All a Goodnight? Unfortunately, the film’s original 1983 VHS release was of such poor quality that it has largely been confined to slasher footnotes ever since, though more recent remasters have made the film much easier to watch.

The killer Santa revival of 1980 wasn’t over yet, though: November would also include the release of the better known Christmas Evil, a psychological quasi-slasher about a man who loses his mind as a child after seeing his mother kissing (and then some) Santa Claus. The man then grows up into a Santa-obsessed adult who works in a toy factory, being largely sympathetic in his downtrodden, sad sack routine until he’s finally pushed too far, snapping as he dons the Santa suit to embark on a spectacularly random killing spree. Modern reappraisal has increasingly heaped praise on Christmas Evil for its far stranger and more psychologically rooted, Taxi Driver-esque take on the killer Santa premise, complete with a bizarrely fantastical ending that defies description. This is one you should really just see for yourself.

Neither of those films energized the kind of emotional outrage that Silent Night, Deadly Night garnered in 1984, however, and I think the reason ultimately comes down to the specific moment when Deadly Night was ultimately released. In 1980, when For All a Goodnight or Christmas Evil were hitting theaters, the idea of slasher cinema was still in its infancy, something being codified as the scions of Halloween coalesced and hit a critical mass. Four years isn’t a “long time” in most respects, but it was an absolute eternity when it comes to the volume of slasher movies that were cranked out in this, the height of the genre’s golden era. Compare the more earnest, shocked-at-their-own-violence tenor of the average slasher film from 1980 with the increasingly jaded and cynical humor of the average release from 1984, and you can see the evolution pretty starkly–Friday the 13th is a very different beast from Friday the 13th Part IV: The Final Chapter. The genre was rapidly evolving in a quest to stay ahead of itself, as viewers sought more and more shocking fare and became inured to the same types of violence.

Audience members with little interest in slasher horror, meanwhile, couldn’t help but take note of how it was proliferating in cinemas, seemingly becoming more and more transgressive every year. The arrival of Silent Night, Deadly Night in 1984 was just seemingly the last straw for some of these particular would-be moral crusaders who had been waiting for the right scapegoat to go to war against: The salacious killer Santa advertising of Deadly Night proved to be just the right agitation to stir that hornet’s nest. And unlike in 1980, when those killer Santa movies passed right by without any of the easily offended taking much notice of them, in 1984 the mass media was more geared to capitalize on American outrage (among the evangelical, anti-smut and obscenity crusaders) by playing up the controversy and inflaming the passions of everyone involved. The performative outrage that was leveled against Silent Night, Deadly Night was ultimately a long-gestating response to the golden age of slasher movies itself, led by exactly the same sort of people who across the Atlantic Ocean would push the British government to prosecute “video nasties” for obscenity in the same year: 1984. It was a symbolic act of protest by Middle America against the garish horror films they assumed were degrading the country’s moral fiber.

Of course, perhaps unsurprisingly, that meant those same offended citizens stopped paying attention pretty much immediately after successfully getting Silent Night, Deadly Night pulled from theaters. How do we know that? Well, less than a month later, 1984’s Don’t Open till Christmas hit theaters, inverting the formula a bit by being a slasher in which not the killer but the victims are all dressed as Santa Claus. Did the picketers grab their still fresh signs and go right back to their protesting on Santa’s behalf? Of course not; the film came and went without any significant blowback or negative publicity. The protestors had made their statement, and wanted to bask in the feeling of having won, while the slasher boom continued merrily onward, unaffected in the grand scheme of things.

The decade would go on to include other killer Santa examples, starting with a string of Silent Night, Deadly Night sequels, or 1989’s Elves, which made Santa’s helpers into antagonists and pit them against an alcoholic former detective turned hero mall Santa. Personally, I’m particularly fond of 1989’s supremely odd French Christmas action-horror hybrid Deadly Games, which basically presaged Christopher Columbus’ Home Alone by telling a story about a brilliant young boy defending his home with a series of traps against a deranged killer dressed as Santa Claus. But as the decade came to a close and the slasher boom finally extinguished itself, the prominence of the killer Santa faded into the rearview mirror … only to be reborn from the 2000s onward in the modern wave of killer Santa movies we still find ourselves in today.

You Can’t Keep a Good Elf Down

Whatever stigma may have once been attached to the horror genre or horror movie fandom, it’s safe to say has effectively washed away over the decades–from the 2000s onward, the mainstreaming of horror has really hit terminal velocity. This includes the freedom to depict formerly taboo topics in a now lighthearted way, which is how we end up with a veritable explosion of killer Santa media. These days, the horror genre is so replete with them that you can scarcely swing a sack of presents without bowling over a knife or axe-wielding Santa, in fact–it’s become a trope ready to be warmed over every year like so many Christmas dinner leftovers.

There are the more “traditional” takes on a killer Santa Claus that place a mentally unstable mortal man inside the red and white suit, such as 2007’s P2 or a segment from 2015 anthology A Christmas Horror Story. There’s also a wave of films that reimagine the mythical character of Santa into one that has always had some kind of wicked or evil nature, mistaken as goodness by humanity–this applies to the likes of 2005’s Santa’s Slay or 2010’s Dutch horror comedy Sint, or the particularly kooky depiction of Santa’s “elves” in 2010’s Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale. Krampus had his own moment in Michael Dougherty’s banger of a 2015 horror comedy. Even Futurama had its violent robot Santa (voiced by John Goodman!), dispensing death and judgement every “Xmas” in the year 3000.

The boundaries of this particular horror subgenre continue to expand, however, to fit new avenues of relevant cultural commentary. Take 2022’s Christmas Bloody Christmas (they’re really fishing for titles now), which reimagined its killer Santa not as flesh and blood but as a malfunctioning robot on a rampage–a killer Santa concept freshly fit for the era of A.I.-driven anxiety. And finally, “killer Santa” has even found itself reclaimed by Hollywood’s inevitable bad-guy-to-antihero pipeline, as in two recent entries: 2020’s Fatman and 2022’s Violent Night, which goes to prove that it’s never really violence that is the problem for American audiences–it’s just that we want to make sure violence is being directed at the right targets.

Consider that evolution, from the days when picketers were angrily chanting and singing carols outside of theaters in an attempt to protect the good name of Santa Claus from the desecration of the Hollywood horror movie industry. In 1984, Silent Night, Deadly Night was considered by many as an affront to basic, universal American values–not just by fringy evangelical kooks but by people as influential as Siskel & Ebert, who were condemning the idea that sick individuals would pervert the character of Santa Claus in this way. And just 38 years later, many of those same people were presumably packing into theaters to watch David Harbour as a grizzled, ex-Viking warrior Santa as he murders an entire mansion full of terrorist mercenaries in Violent Night, cheering Kris Kringle on to ever-greater heights of brutality. The depiction of a killer Santa hasn’t merely become an acceptable villain for stock holiday horror–he’s now even a protagonist we can get behind as he metes out holiday justice to those who deserve it. He’s an avenging angel! Go get ‘em, Santa!

In a way, is that not the most appropriate take for the character, given his historical roots as an amalgamation of various figures who spent just as much time punishing as they did doling out rewards? Modern holiday cinema recognizes the character as a two-faced, Christmastime Janus: Santa giveth, and Sinterklaas taketh away.

Jim Vorel is Paste’s Movies editor and resident genre geek. You can follow him on Twitter or on Bluesky for more film writing.