Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth Is Surprisingly Void of Manic Emotion

Defined by stark minimalism, Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth is an undeniable directorial flex. Coen commands the film’s slickly sparse black-and-white visuals alongside his cast of renowned actors, yielding a final product saturated with artistic determination—but one stripped of any semblance of madness or mania. The highly stylized aesthetic of the film—coupled with regretfully restrained performances—transform Macbeth into an all too tedious tragedy.

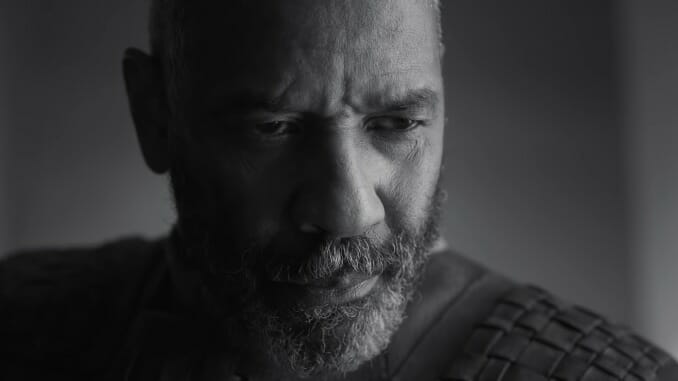

Though it hardly requires recapitulation, The Tragedy of Macbeth follows the eponymous ruthless Scottish general (Denzel Washington) and his Lady (Frances McDormand) in the wake of a jarring prophecy. Three witches (performed with singular unnerving nuance by Kathryn Hunter) inform Macbeth that he shall inherit two titles: First Thane of Cawdor, then king of Scotland. Macbeth is appointed Thane of Cawdor almost instantly afterwards, and upon hearing that the first part of the prophecy has been fulfilled, Lady Macbeth becomes eager for her husband to assume the Scottish throne. She eventually convinces Macbeth to murder King Duncan (a brief Brendan Gleeson) to speed up the process—the ensuing guilt, anxiety and instability driving both King and Queen to the depths of madness. Shakespeare’s shortest tragedy, Macbeth is only a little over half as long as Hamlet (his longest), and as such is often noted for its characters—and their intentions—containing less complexity compared to his other plays. Yet the play’s brevity is also what lends it so well to cinematic interpretation, as it’s generally less complicated to add detail where it is lacking as opposed to reimagining fleshed-out facets.

Tackled by previous filmmakers such as Orson Welles, Roman Polanski, Béla Tarr and most recently Justin Kurzel, retellings of Macbeth often incorporate a particular stylistic flourish or departure in contrast to William Shakespeare’s original folio. Welles’ Macbeth (played by the director himself) is distinguishable by his blatantly detestable nature. Polanski’s rendition—his first film after the brutal murder of Sharon Tate—is similarly streaked with frenzied bloodshed. Tarr directed a Hungarian TV version of The Scottish Play, captured in 62 minutes with just two takes. In 2015, Kurzel crafted his Macbeth with an arthouse intensity, opting to relish in riveting realism. Each (notable) adaptation of the Bard’s breeziest tragedy is intentional in the way it leaves its mark—be it through performance, brutality, abstraction or reconstruction. Coen’s Macbeth, conversely, attempts to distinguish itself in comparatively cautious ways: Washington and McDormand occupy roles typically filled by younger actors, while the film’s milky white and dense black contrast enhances the otherwise barren landscape.

The dismal and deserted styling immediately conveys absence, which points to the missing half of the Coen Brothers duo. The Tragedy of Macbeth signals Joel’s first solo filmmaking endeavor since the inception of the pair’s career with the 1984 breakthrough Blood Simple (also starring McDormand). The brothers have typically written, produced and directed their films jointly (though until 2003, guild rules prevented the duo from sharing the title as director and producer, with Joel and Ethan respectively taking credit for each role), making Macbeth a particularly loaded endeavor—it must fit into the director’s existing co-created catalogue while defining Joel’s standalone writing/directing prowess.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-