What We Left Unfinished Invites Analysis of Afghanistan’s Lost Films as It Leaves Us Wanting More

The promise and potential of unseen movies, lurking in basements and archives, is always an exciting one. Directors leap at chances to play Indiana Jones, and we get the thrill of seeing a movie that’s often a more direct historical artifact than what we’re used to watching. Not only are these movies usually a few decades old, but there’s always a reason why they’ve been squirreled away in the first place. Lost footage that’s suppression had direct political links has been touched on by Summer of Soul’s documentation of the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival earlier this year, but What We Left Unfinished has a few added twists. Openly grappling with the ties filmmaking has to the state and by extension its rulers, the feature debut from writer/director Mariam Ghani—daughter of Ashraf Ghani, the current president of Afghanistan—examines the Afghan film industry’s relationship with its turbulent late 20th century (spanning the dissolution of the monarchy in the ‘70s to the Taliban in the ‘90s) through the lens of its incomplete works. Clocking in at barely over an hour, What We Left Unfinished feels a bit unfinished itself, and its compelling premise will leave history buffs, media scholars and those simply looking for a good yarn about lost art wanting far more.

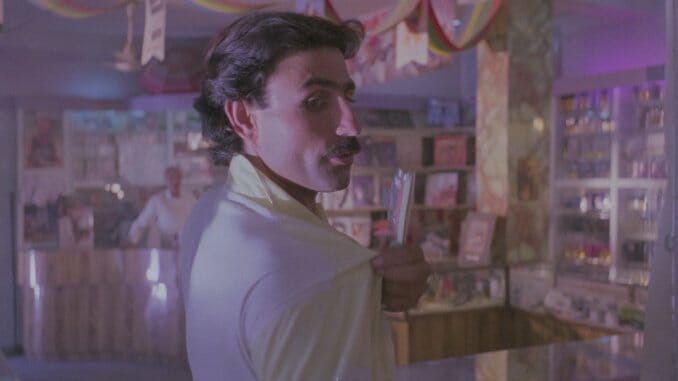

Despite being a film that spans decades and entire rises and falls of governments, What We Left Unfinished is extremely focused. Rather than give detailed historical context, it sticks closely to the archival footage from five unfinished, disrupted or lost films from Afghanistan’s decades of regime changes: The April Revolution, The Black Diamond, Downfall, Wrong Way and Agent. And they’re all distinctly engrossing. Striking, crisp cinematography places us in vast, sandy and mountainous landscapes or gives us a too-close view of a rolling tank. Expressionistic acting in intimate interiors makes the rarely present audio tracks superfluous. That Ghani juxtaposes settings with their present-day realities and edits interviews so that we clearly understand that guns are firing real bullets (Blanks? Scarce. Live rounds? Galore.) make a larger point clear: All movies reflect their times, even if some are a bit closer to reality than others.

This broad idea is filtered through and complicated by about ten different points of view, the unpacking of which is part of the fun. These movies were filmed under one set of sociopolitical circumstances, often stopped because of a change, then presented by an American descendent of the current leader with commentary from the directors/actors themselves (all of whom have differing opinions about the past governments and are clearly speaking to someone highly influential in the present). It’s easier to follow the plots of the unfinished films than successfully navigate the labyrinth of personal ideologies. And that’s not even counting all that Ghani brings to the table, which mainly comes across as excitable expectation towards the highly subjective media she’s laid bare. This has to mean something, and she gives it to us to find our own. Though it’s admittedly more engaging in theory than in practice—partially because an informed viewing requires a working knowledge of Afghan-Soviet relations, the Taliban, the Mujahidin, the Afghan film industry and much more—it still presents the propagandistic powers of film as clear as day.

While documentaries always wear this a bit more on their sleeves than most fiction films, try watching a big Hollywood action blockbuster without noting the copious tech provided (and advised upon) by the U.S. military or the latest Conjuring without seeing the victorious and virtuous Christians (turned from scam artists to saviors in the narrative) stamp out those dirty ol’ demons. Ideology is as inescapable in art as in any other facet of life, and What We Left Unfinished succinctly lays this bare…some examples of which are more literal than others.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-