War of the Worlds at 20: Steven Spielberg’s Bleak, Reactive Anti-Blockbuster

There was a notable shift in Steven Spielberg’s filmography after his unprecedented success in 1993, in which he both won the Academy Award for Best Picture with Schindler’s List and created the highest-grossing film of all-time with Jurassic Park. Schindler’s List seemed to indicate a new direction in Spielberg’s career, in which he would emphasize important stories of world history, including Amistad and Saving Private Ryan.

Jurassic Park presented a different conundrum. While Jaws, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and E.T. The Extra Terrestrial had been cited as the definitive “popcorn movies” of the previous decades, Spielberg had somehow given the next generation an adventure epic that pushed the boundaries of computer generated imagery to their fullest potential. Topping his own success would prove to be challenging, as The Lost World: Jurassic Park was a disappointment that suggested Spielberg no longer had interest in four-quadrant entertainment. Spielberg’s talents seemed better reserved for more “intellectual” fare; Catch Me If You Can was a deep character study about lonely people, and even a sci-fi thriller like Minority Report dealt with serious themes of restorative justice and predestination.

Word that Steven Spielberg would be adapting H.G. Wells’ iconic science fiction classic The War of the Worlds may have been exhilarating to an audience walking out of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, but to an audience that had experienced the meditative cynicism of A.I. Artificial Intelligence, the move felt regressive. Spielberg had nothing left to prove by making a blockbuster intended for a mass audience, particularly when it came to stories about extraterrestrial visitors. Ironically, War of the Worlds would ultimately prove to be one of Spielberg’s most profound films about humanity; within the ashes of catastrophe, mankind is revealed to be selfish, unorganized, and incompetent as it faces an existential threat.

Although Minority Report’s analysis of surveillance technology was eerie within the immediate aftermath of 9/11, the film was well into production by the time that the attack on American soil had commenced. The ramifications of September 11, 2001 were felt by all of Hollywood within the immediate aftermath, but Spielberg directly examined the consequences of the “war on terror” within his two 2005 films. If the thesis reiterated by the administration of President Bush suggested that collective grief would offer a means of uniting people across party lines, both War of the Worlds and Munich offered a gutting dose of reality.

In Munich, the violence is generational; although the “Black September” tragedy is the inciting incident, it only stoked the tension between Israelis and Palestinians that had been brewing for several lifetimes. However, War of the Worlds captured the stark terror of 9/11 as a singular incident, in which a threat appeared out of nowhere to bring civilization to its knees. As urban centers are decimated and fear takes hold of society, there is little time to be anything but reactive. Those that survived the first wave of the attack are left to wonder if this is the new reality, and whether the world will ever know peace once more.

A talking point perpetrated within the months after 9/11 is whether an attack so destructive was inevitable; America had been a superpower that has inflicted catastrophic damage upon other nations, and its citizens have never felt trepidation about an attack of the same magnitude on their own soil. Spielberg suggests a similar anxiety within the opening moments of War of the Worlds, in which Morgan Freeman’s narrator describes the dominion of Earth that has caused extraterrestrials to desire its control. Although War of the Worlds does incorporate aspects of anti-capitalism that have become integral to Spielberg’s 21st century canon, the film does not place blame on humanity for its indulgence. Rather, it suggests that in their sustained supremacy, mankind has taken for granted everything they should have cherished.

Spielberg’s complex childhood, which he would go on to unpack in his semi-autobiographical film The Fabelmans, spawned recurring themes of broken families, divorced parents, and lost boys within nearly all of his work. Where films like Empire of the Sun or E.T. examined the complexities of adolescence, War of the Worlds sought to empathize with a divorced, bitter father who is forced to step up in his responsibilities. Unlike a character like Robin Williams’ Peter Pan in Hook or Sean Connery’s Henry Jones Sr. in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Ray Ferrier isn’t a misunderstood, whimsical hero who rediscovers a childlike sense of wonder. Rather, he’s a failed parent whose optimism was eroded before the events of the film even began.

While Tom Cruise’s casting in Minority Report provided him with one of his best roles, it wasn’t necessarily a performance that challenged the audience’s perception of his star persona; his role as a wrongfully accused Precrime officer had the same sense of authority and bravery that made him so perfect for the Mission: Impossible franchise. War of the Worlds, on the other hand, asked Cruise to be pathetic, needy, and at times aggravatingly ignorant; although his complaints about disappointing work hours and an ungrateful ex-wife are relatable, it’s odd to see such banal rhetoric coming from someone as world-renowned as Cruise.

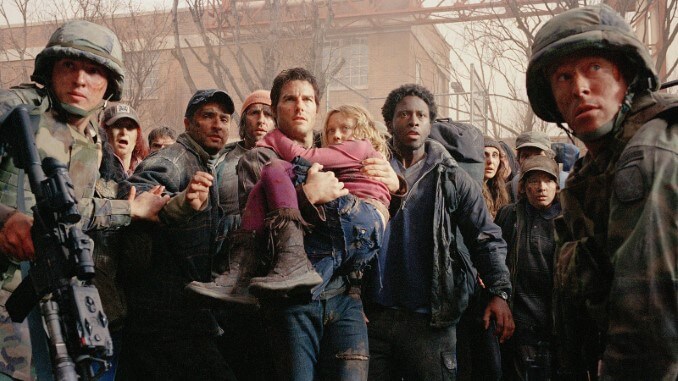

Cruise had certainly played dark, complicated characters before, but never someone as unexceptional as Ray; there’s a hint of romantic tragedy within Eyes Wide Shut’s Bill Harford or Magnolia’s Frank T.J. Mackey, but Ray’s entire life has little significance within the devastation of Earth at the hands of Martian invaders. Bill is a Hitchockian hero in the sense that he is “an ordinary man caught within extraordinary circumstances,” and Cruise serves as an appropriate audience avatar as he experiences the chaos that emerges. The ability to turn someone as larger-than-life as Cruise into an “everyman” underscored the overwhelming stakes and scale of the terrifying extraterrestrial invasion in War of the Worlds.

Spielberg’s portrayal of domesticity is rich with irony, as Ray is tasked with taking care of his children, Robbie (Justin Chatwin) and Rachel (Dakota Fanning), as a result of a devastating thunderstorm that separates him from his ex-wife, Mary Ann (Miranda Otto). Although there is mounting suspense as Spielberg slowly builds to the reveal of the tripod alien attackers, the uncomfortable exchanges with the Ferrier family contain a different type of tension. A prolonged, aggressive game of catch between Ray and Robbie is the perfect summation of their fruitless relationship; later, the scream Rachel makes as they drive along the East Coast could only be given by a child who does not believe that they have a competent guardian.

More terrifying than the presence of the aliens themselves is the futility of finding a protected area of shelter. The Ferriers haphazardly travel from New York to New Jersey, then back to Boston, fleeing as each supposed safe haven is decimated. An initial moment of violence when the tripods vaporize a group of civilians perfectly captures the removed sense of horror one might have felt watching the Twin Towers collapse on television, but it’s the death of Ray’s friend Manny (Lenny Venito) that indicates that the danger is not theoretical. In an inverse of what most disaster films would do, Spielberg reveals the context of the threat before delivering a more intimate tragedy that psychologically traumatizes the protagonists.

Spielberg learned from Jaws that it’s more terrifying to keep his villain in the shadows, and War of the Worlds is clever in the slow reveal of the alien designs. It’s often more chilling to examine the aftermath of a conflict, as the devastated suburbia Ray and his children trek through bears a striking resemblance to war-torn China in Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun. It would have been unwise to mask the aliens for too long, but Spielberg complicates their revelation with a scarier component- the tripods have protective shields, which make a majority of humanity’s defenses completely useless. It inspires yet another instance in which Ray must admit to his children that he doesn’t have an actual solution, as the planet is not equipped to protect them from such advanced technology.

Although Chatwin’s performance caught the most flack from critics during the initial release of War of the Worlds, Robbie’s decision to join the counter-offensive may be the film’s most radical parallel to the post-9/11 landscape. Those stepping up to serve as Earth’s defense aren’t altruistic, emboldened heroes, but angry young men like Robbie, who see violence as the only means of finding purpose. Robbie may still contain shards of innocence, but he chooses to take up arms with knowledge that the battle is futile. It’s among Spielberg’s most crushing observations about the collapse of the “nuclear family,” that many would rather choose to face their likely demise than be vulnerable in front of their loved ones.

It was bold of Spielberg to initially present Ray as a miserable, spiteful character, then steadily reveals him to be more virtuous than many of the other humans scavenging in the aftermath. As the survivors crawl over one another for any source of food or medical supplies, Ray and Rachel must place their faith in Tim Robbins’ Harlan Ogilvy, an unstable ambulance driver who offers them temporary shelter. Although Harlan isn’t malevolent, his inability to cope with the body horror of the aliens’ harvest of human flesh results in a mental breakdown, in which a reluctant Ray must kill him. It’s among the darkest moments in any Spielberg film, as it presents an impossible scenario in which Ray must commit an unthinkable act for the sake of his daughter’s life; although it’s suggested that Ray made the only rational choice within the circumstances, it doesn’t make the visual of America’s leading A-lister brutally executing a mentally ill man any less disturbing.

Although Ray’s transformation into a more heroic protagonist struck some as a betrayal of the film’s more grounded beginning, Spielberg deprived his version of War of the Worlds of the global context of its cinematic predecessor. The 1953 film by Byron Haskin details how Doctor Clayton Forrester (Gene Berry) found a means of wounding the alien invaders, which prompted him to bring his findings to a group of military scientists in Los Angeles. Though Ray does find a way of destroying the tripods from within, his strategy is only used by a relatively small group of soldiers and civilians in Boston. Ray’s defining act of bravery is intertwined with his own survival, but does not have any lasting consequences that impact humanity as a whole. The smaller scale of the conflict helps keep Spielberg’s film grounded, which in turns makes Ray’s arc more authentic; it doesn’t immediately suspend the viewers’ disbelief when Cruise becomes an action star once more, as the audience has already seen the insecurities that plague him.

War of the Worlds’ denouement has also become a subject of criticism since its release. The alien invaders are killed as a result of latent microbes that humanity has adapted to, but it was never intended to be an uplifting finale in the vein of Independence Day’s rousing conclusion. It’s rather disturbing that an invading race incapable of surviving on Earth would be able to supersede humanity’s mightiest defenses before its inadaptability is revealed, as Spielberg suggests that the survival of either species is quite fragile. It’s also an indication that mankind itself would turn on itself before the inevitable cure was found, as none of the inflammatory rhetoric ended up mattering.

The final moments of War of the Worlds struck another parallel with Munich, which rather infamously ended with Avner Kaufman (Eric Bana) becoming so haunted that even intimate moments with his wife (Ayelet Zurer) are disrupted by dark visions. If Munich implied that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was destined to last forever, War of the Worlds showed the great lengths taken to restore a semblance of normality to Ray’s family life. The reunion of Ray, Robbie, Rachel, and Mary Ann is a brief moment of catharsis, but there’s no suggestion that it will result in a restoration of domestic bliss.

Although it may have been impossible during its initial rollout to distance War of the Worlds from its aggressive marketing campaign, the film’s technical achievements have aged rather well, particularly when compared to other Spielberg ventures of the last two decades. The washed-out, cartoonish style of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull and The BFG resulted in a lack of tactility, but the mechanized design of the tripods gave War of the Worlds an evident parallel to legitimate tools of war. Janusz Kamiński has often been praised for his immersive cinematography, and the tracking shots in War of the Worlds are among the most kinetic of his collaborations with Spielberg; John Williams’ score is also notably dour, as the rhythmic crescendos that animate each action sequence are interspersed with melancholy moments of grandiosity, which inspire comparisons to the monster movie themes of the 1950s.

Spielberg’s first son, Max, was not born until June of 1984, and there’s a notable difference within the ways in which he depicts children in the immediate aftermath; it is unlikely that Spielberg would have depicted the brutal death of a young boy in Jaws, the enslavement of children in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, or the peril of kids in Poltergeist had he already been raising a family of his own. Although some have pointed to Spielberg’s parenthood as the reason he often slipped into sentimental storytelling, War of the Worlds evokes the kind of horror that could have only been conceived by someone terrified about the world that they would leave behind for their children. The film was not merely a subversion of ‘50s B-movies or a commentary on American haughtiness, but a realization of Spielberg’s own anxieties. Only a filmmaker of Spielberg’s imagination would have been able to craft War of the Worlds into such a nightmare.

Liam Gaughan is a film critic, writer, and entertainment journalist with over twelve years experience writing about popular culture. His bylines include Polygon, Dallas Morning News, Dallas Observer, High on Films, Central Track, Collider, Taste of Cinema, Slashfilm, and Movieweb. He also posts ramblings and thoughts on Letterboxd and X at @TheLiamGaughan.