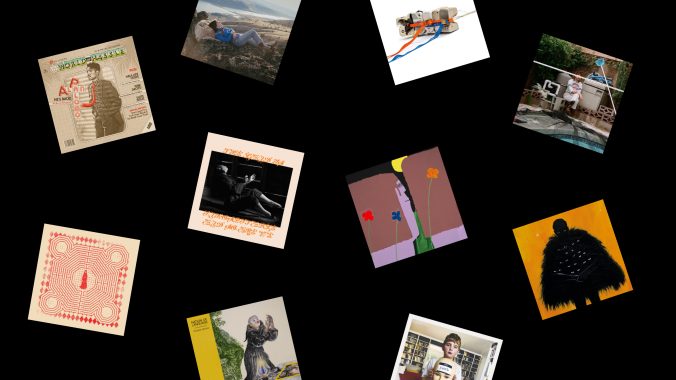

The Best Albums of September 2023

Featuring The National, Mitski, Slowdive and more

It’s a broken record thing to say, but September came and went quicker than ever this year. It did give us five Fridays of new music to get lost in, though, and that’s what matters most! The heat is slowly dissipating, but the albums keep getting better. This month offered us everything from synth-pop soaked in 1980s gloss, a heart-wrenching country joint, lo-fi indie rock laced with hip-hop backbeats and, of course, a near-masterpiece from one of the best working bands in the world. From a great sophomore record from Slow Pulp to Mitski’s poised and grand return to Slowdive’s glorious next chapter, let’s take a moment to recap this great month of unmissable music. Here, in alphabetical order, are the 10 best albums of September 2023. —Matt Mitchell, Music Editor

Alan Palomo: World of Hassle

Even though the atmosphere Alan Palomo has constructed fits squarely in a late-Cold War setting, he contextualizes his ideas in a way that feels both timeless and contemporary. Take, for instance, the discussion of late-night texts on “Stay-at-Home DJ,” allusions to “fuck, marry, kill” on “Nobody’s Woman” or the reference to a line of dialogue from the 1955 Best Picture-winning drama Marty in “Big Night of Heartache.” This balancing act between the novel and the nostalgic can be a tricky feat to pull off, but Palomo makes it subtle enough that it doesn’t feel like a glaring anachronistic distraction.

Although Palomo is so evidently adept at emulating rather than sentimentalizing the past, World of Hassle does, sometimes, feel a touch pastiche-y. Especially as it enters the moody second half, the album begins to mirror what M83 did in 2016 with Junk, leaning so hard into the cheese and schmaltz of late-‘80s muzak that it almost verges on fetishistic parody. But Palomo’s sun-soaked, salt-rimmed, neon-tinged world has such an immersive, hypnotic pull that its more derivative tendencies don’t really matter. World of Hassle oozes so much personality that a two-hour vaporwave YouTube video could never replicate. Like he’s done with Neon Indian, Palomo situates the listener in a time and place that still haunts our culture, but invites us to get lost in the memory—and, as long as he’s leading the way, there isn’t much to worry about. —Sam Rosenberg

Anjimile: The King

Where his debut album Giver Taker explored a more delicate form of personal storytelling—often delivered via nimble, unadorned acoustic guitar flourishes in line with Sufjan Stevens’ Michigan or Illinois—Anjimile works on a much grander scale across The King, as if conjuring a vision of what folk music would sound like if it was delivered by Philip Glass. It’s a record akin to speaking with the force of every voice like Anjimile’s that has been left silent for centuries, arriving with a volume and might that feels primed to shatter anything that gets in its way. Guitar strings now thrum and buzz where they once felt gentle, and Anjimile’s voice is occasionally put through bass-heavy filters or joined by a calamitous, otherworldly choir sonorous enough to make the speakers rattle. Anjimile’s choice to radically reconfigure the basics of his sound is nothing short of revelatory. Much of The King comes solely from Anjimile’s guitar and voice, even if the record’s production makes it sound as if the tracks are being wrought by a cataclysmic full band.

On the climax of “Mother,” Anjimile twists their guitar into a wounded howl of a thing, like a klaxon cry at the climax of a Godspeed You! Black Emperor piece. The pure range of sounds that Anjimile and producer Shawn Everett are able to invoke calls to mind the work BJ Burton made with Low on their final albums, reenvisioning the simplest instrumentation possible until it sounded anything but its source. Here, his acoustic guitar takes on a similarly striking effect: harnessing all the tenderness commonly associated with it on tracks like “Father,” before being torn apart in a distortion-heavy flurry and redirected as a sharp percussive implement on “Black Hole.” If there’s one thing that The King’s sound especially works to highlight, it’s Anjimile’s lyricism. Much of Giver Taker operated in similar narratives of family history and self-definition, but The King weds that focus to its sound even further, its assuredness more emphatic, its openness all the more vulnerable. And, on tracks like “Harley,” where Anjimile sings into a reverb-heavy soundscape for one of the rawer personal moments of songwriting, the transition explores new, audacious configurations that their emotional side can take. —Natalie Marlin

Field Medic: LIGHT IS GONE 2

light is gone 2 is framed as a sequel to Sullivan’s 2015 debut album as Field Medic, but it was largely born out of an attempt to manipulate the musical approach he established on that first release. Sullivan has largely been a guy with an acoustic guitar and a boombox, but this record seeks to blend digital recording—replete with the attendant synth and drum machine accouterment—into his established palette. While certainly adding variation and, according to Sullivan, kickstarting a rush of creativity, it doesn’t fundamentally change what the project of Field Medic is at its core—a fact that can largely be attributed to Sullivan himself, a creator of such idiosyncrasy and personality that it almost overshadows whatever changes in technique or style he might attempt.

If you’ve tracked the many moments of autobiography that run through Field Medic’s discography, then you’re likely aware that most of his aforementioned portrayals of addiction are now sung in the past tense. They are demons with receding shadows, half-remembered nights further blurred by the distance of time and personal growth, but the emptiness of their absence is not as freeing as one might imagine. The stuttering, percussive “everything’s been going so well” is drenched in the kind of guilt one might feel when they are, “too self absorbed and depressed to see everything’s going well,” a kind of self-imposed survivor’s remorse run amok. It’s not that Sullivan suddenly fears honesty, but, rather, the kind of disappointment that might come from everyone’s assumption that you’ve crossed some imaginary finish line. The light might still be gone, but for Sullivan, darkness and light are always relative. —Sean Fennell

Margo Cilker: Valley of Heart’s Delight

Margo Cilker’s approach to construction transcends reference. I’m transported to someplace familiar, though I cannot begin to say where, exactly. The Washington-via-California musician put out her debut album Pohorylle just two years ago; but, on Valley Of Heart’s Delight, it sounds like she’s got a century’s worth of stories to tell. To segue from “Lowland Trail” into “Keep It On A Burner” is a huge flex on Cilker’s part. Here, she takes a beautiful country musing and turns it into this gigantic, rewarding soundscape set adrift with Kelly Pratt’s horns and Jenny Conlee-Drizos’ crystalline piano.

What’s, maybe, most remarkable about Valley Of Heart’s Delight is how unabashed it is about adopting the tradition of country music while also, simultaneously, chiding the very concept of embracing such a silly history. Twang is not a vessel to step into for Cilker, it’s a way of life that surrounds her every beating step. The upbeat tango and two-step of “Steelhead Trout” sounds like a behind-the-scenes look into a weekend for Cilker and her peers, while “Santa Rosa” finds her detailing the places she’s left behind—from forgotten friends to the alien remembrance of kin, a wayfaring token of the singer/songwriter heroes she pulls greatly from. Through lessons taken from the songbooks of John Prine and Gillian Welch, there are inflections of gospel, cowboy chords, soft rock and Americana running through the veins of each track. And, at no point on this album does Cilker ever waver in her convictions, her own prophecies or her own pace towards finding the righteousness she greatly wants—all of which feel so deftly urgent and necessary. —Matt Mitchell

Mitski: The Land is Inhospitable and So Are We

Mitski’s seventh album feels, all at once, like a much-needed course correction away from 80s style synths growing staler with each use and like her lowest stakes release yet. The towering expectation and deafening hype that surrounded Laurel Hell seemed to have died down, leaving her free to exhale. The Land is Inhospitable and So Are We finds Mitski breaking new ground, building transcendent songs with the accompaniment of acoustic guitars, pedal steel, a string section and an entire 17-person choir. These resplendent pieces fit together to form fascinating, delicately arranged songs.

One of the most striking things about The Land is Inhospitable and So Are We is how it succeeds while sacrificing the reliance on melody that undergirds some of Mitski’s best songwriting thus far. There is nothing as electric as “Nobody,” nothing as distorted as “Your Best American Girl.” And yet, this is her finest collection of songs. There’s a beauty to her pastoral vignettes that resonates without the need for traditional pop hooks. It’s not music that’s suited to arenas, and maybe that’s the point. The album ends with a proclamation of her own power and agency. “I’m king of all the land,” she sings on “I Love Me After You,” before unleashing heavy drums and guitar fuzz. Mitski can do anything she wants to now, and we’re better off under her reign. —Eric Bennett

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-