Darrell Scott and the Ghost of Hank Williams

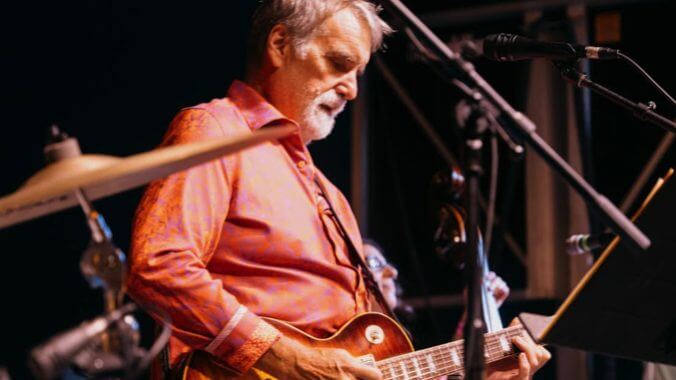

Photo of Darrell Scott at the Bristol Rhythm & Roots Reunion by Joel Jansen courtesy of Victory Lap Media

A couple of hours before their set at the Bristol Rhythm & Roots Reunion this month, Darrell Scott’s Electrifying Band grabbed dinner at the Burger Bar on the Virginia side of this state-straddling city. Legend has it that this tiny, wedge-shaped eatery (nine stools and a diagonal counter) at the corner of Piedmont and State Streets was the last place anyone heard Hank Williams speak.

It was Wednesday, December 31, 1952, and Hank’s driver Charles Carr supposedly stopped at the bar for some food and asked the ailing singer slumped in the back seat if he wanted anything. His bloodstream already swimming with morphine and beer, Williams whimpered, “No.” He was dead by the time the sun rose again.

For Scott, who was raised in Indiana by a Hank-loving daddy from Kentucky, this tale has special resonance. He released the album Darrell Scott Sings the Blues of Hank Williams in 2020 and has explored the tug-of-war experienced by Hank and so many Americans: the pull of the rural-or-small-town roots and the attraction of big cities and new horizons.

Scott addresses this rural/urban divide in our culture on all three albums he produced this year: Old Cane Back Rocker by the Darrell Scott String Band, released in August; Morning Shift by the Steep Canyon Rangers, released this month; and Critterland by Willi Carlisle, finished but due in January. These are three of the best acoustic projects of the year, but Scott is also taking his electric band on tour this fall including stops at Bristol and Hank’s 100th birthday celebration in Montgomery, Alabama.

In Bristol, the four musicians walked down the block and crossed State Street into Tennessee to take the festival’s Country Mural Stage, so named because giant, painted likenesses of the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers stare down from the brick building next door. Bristol earned its nickname as “The Birthplace of Country Music,” because the Carters and Rodgers auditioned and made their first recordings down State Street at a hat-and-glove factory during a 12-day period in the summer of 1927. And that’s why the Burger Bar story has such resonance; it happened in the same downtown neighborhood.

The set’s second song was Williams’s “The Blues Come Around,” done as a blues-rock stomp with Scott’s sunburst Les Paul guitar adding cardiogram spikes to the beat and Reese Wynans’ B-3 organ flooding the empty spaces. “I think Hank is a blues singer,” Scott told the crowd, “though no one calls him that. I also think he’s a singer-songwriter, though no one calls him that either.”

Wynans is best known as a member of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s Double Trouble, and he brought that same edge to Hank’s songs as a member Scott’s electric band. It wasn’t that Scott and Wynans were trying to take Hank out of his country context; it was more that they were calling attention to the blues element that was there all along. They were reminding us that poor Whites in the South have long known the blues in every low-paying job, every troubled marriage and every brief explosion of joy.

“Why can’t you take a Hank song and blues it up?” Scott asked me in 2020. “It’s not something I’m putting in there; it’s already there. I knew certain Hank songs could handle that very easily. So I made a list of 25 Hank songs that might work—and not the real obvious songs. The brain would say, ‘More people will recognize ‘Hey, Good Looking,’ but the heart would say, ‘You know the good stuff, why not use them?’ ‘Men with Broken Hearts’ from his Luke the Drifter records is not as well known, but people need to hear that now. Certainly we know about that in our modern world.”

The Bristol set included two more songs—“My Sweet Love Ain’t Around” and “Fool About You”—from Hank’s recordings plus two Scott originals that mention Hank in the lyrics. “Hank Williams’ Ghost” is one of those early-morning, wondering-what-it’s-all-about songs; it begins with the notion that “hillbilly sins have an odor all their own” and ends with the confession that “we hurt the ones we love the most and we blame it on Hank Williams’ ghost.”

The other Hank-related original, “One Hand on the Wheel,” is from Scott’s new string-band album. It’s a story song about a down-on-his-luck guy trying scrape together the bus fare to Shelbyville, Kentucky, where his brother might have a line on a job. Before he goes, however, he’s going to stop at the local tavern, where the juke box is free till noon. “ I always play Hank Williams,” the song’s narrator says, “just like my daddy did, where it’s laid out on the table, and the meaning never hid.”

“There’s no trickery in Hank,” Scott says now. “There’s no Dylan in Hank, no Dylan Thomas poetry. ‘I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry’ was as poetic as he got. Everything else was pretty direct. He didn’t have a bone in his writing body that wanted to hide anything. So I loved it when that line came up in ‘One Hand on the Wheel.’ There’s so much praise for mysterious writing, but I wanted to say, ‘Hey wait a minute; let’s not forget how simple things can be and still be so impactful.’”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-