The Peculiar Job of the In-House Lyricist

A Curmudgeon Column

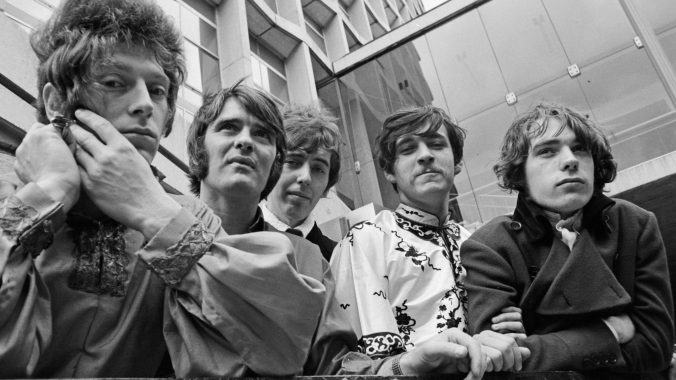

Photo by Ivan Keeman/Redferns/Getty

The recent deaths of Keith Reid (March 23 at age 76) and Pete Brown (May 19 at age 82) remind us of one of most peculiar jobs in rock ‘n’ roll: the in-house lyricist. Reid didn’t appear on stage with Procol Harum, but he wrote most of the band’s lyrics and was almost always in the wings watching his bandmates sing his words. Brown had much the same role with Cream.

There’s a compelling logic to this approach. For each job in music, you want the most talented person in that role. You wouldn’t want a talented poet doing a half-assed job playing drums, and you wouldn’t want a talented bassist doing a half-assed job writing lyrics. That makes sense, but the results of using an in-house lyricist have not always been happy ones.

Both Reid and Brown were poets before they were lyricists, and they stumbled in the transition from one to the other. They each trafficked in the kind of flowery language that schoolboys associate with poetry. Reid’s opening lines for Procol Harum’s biggest hit, 1967’s “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” were: “We skipped the light fandango, turned cartwheels ‘cross the floor.” Brown’s opening lines for Cream’s biggest hit, 1966’s “I Feel Free,” were: “Feel when I dance with you, we move like the sea. You, you’re all I want to know.”

That’s a long way from Jerry Leiber’s streetwise, vernacular lyrics for the 1959 hit, “Love Potion No. 9.” You could immediately picture the scene and grasp the situation when the Clovers sang, “I took my troubles down to Madame Rue, you know, that gypsy with the gold-capped tooth. She’s got a pad down on Thirty-Fourth and Vine, selling little bottles of Love Potion No. 9.”

Leiber was a kind of in-house lyricist (and producer) for rock ‘n’ roll bands such as the Coasters and Drifters, but he was never considered a band member. He came out of an older Tin Pan Alley tradition, where songwriters wrote the songs and singers performed them. But his long-term relationship with those bands worked two ways: Leiber’s lyrics helped define each band’s personality, and that personality shaped the kind of songs he and his composer partner Mike Stoller wrote for each in turn. They could be comic for the Coasters, while being romantic for the Drifters.

Allen Toussaint served much the same role for such New Orleans acts as Irma Thomas, Lee Dorsey and Aaron Neville. Toussaint’s opening verse for Thomas’s 1962 single “It’s Raining” evokes a scene and conflict as efficiently as Leiber’s. “It’s raining so hard,” Thomas sang, “looks like it’s gonna rain all night, and this is the time I’d love to be holding you tight…. Sitting by my window, watching the rains fall to the ground.” There’s something to be said for turning everyday language into such vivid passages.

Leiber and Toussaint paved the way for other non-band member lyricists: Reid, Brown, the Grateful Dead’s Robert Hunter (who died in 2019), the Blue Oyster Cult’s Patti Smith, Elton John’s Bernie Taupin and the Beach Boys’ Tony Asher. These lyricists were crucial to the sound and persona of the acts they worked with, but they didn’t perform on stage with them. This placed them in an awkward limbo—in the band, but not in the band—exacerbated by the snobbery of musicians toward anyone who isn’t accomplished on an instrument.

Just as many rock guitarists react to the snootiness of jazz and classical musicians by overplaying, so do many rock lyricists react to the condescension of rock guitarists by overwriting. In the same way a self-indulgent guitar solo can be stuffed with a rapid-fire geyser of high, squealing notes, self-indulgent lyrics can be crammed with polysyllabic nouns and non-sequitur adjectives. Reid was often guilty of such overreaching.

Reid wrote not about the lives we live but about a dreamscape populated by mythological figures from a romanticized past. That was bad enough, but then he tried to heighten his stories with tortured similes and garbled syntax. On Procol Harum’s second biggest hit, “Conquistador,” for example, Reid had Gary Brooker sing, “A vulture sits upon your silver shield, and in your rusty scabbard now, the sand has taken seed, and though your jewel-encrusted blade has not been plundered still, the sea has washed across your face.” That’s neither vernacular nor literary; that’s preening.

But prog-rock was made for such bombast, so it’s no wonder that the non-performing-lyricist band member was so often employed by art-rock and jam-band outfits such as Renaissance (Betty Thatcher), King Crimson (Peter Sinfield), Rush (Pye Dubois) and Phish (Tom Marshall). These examples do not lend much support to the notion that a non-performing lyricist is a good idea.

But it can be. Just look at Robert Hunter, whose lyrics translated the Grateful Dead’s music into a perfect blend of campfire cowboy songs and hand-me-down oral fables. There’s a romantic glow to his words, and that irritates some people, but his words complement the Dead’s psychedelic bluegrass as aptly as Lou Reed’s fit with the Velvet Underground’s urban-decay garage-rock.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-