Passion Pit

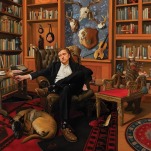

When I speak to Michael Angelakos on July 12, the Passion Pit frontman appears to be in good spirits, rambling through genuinely heartfelt tirades about his gorgeous, dynamic sophomore album, Gossamer. Though his new material is sonically inventive, as bright and infectious as anything on Manners, his overnight-sensation debut, Gossamer was inspired by a myriad of dark sources: Angelakos’ bouts with alcoholism, personal and creative turmoil, and his struggles with bipolar syndrome and manic-depression. But Angelakos speaks of these problems with honesty and clarity, like a man awoken from a year-long emotional hangover, now suddenly thrust into the sunlight, squinting in the wake of troubles. He speaks of this turbulent time in hindsight, often with a boyish giggle trailing every confession.

The 25-year-old musical auteur sounds creatively fulfilled, as he very well should be. Angelakos is proud of what he’s accomplished musically on Gossamer: blown away by the layered, speaker-blowing bass tones he recorded with engineer Alex Aldi and producer Chris Zane, mesmerized by the angelic harmonies created by him and Swedish a capella group Erato, smugly satisfied by the enveloping synthesizers piled in every nook and cranny. But he also seems to be in a good place personally. At the time of our conversation, he’s just wrapped up a music video shoot for the R&B-inspired slow-jam “Constant Conversations,” based on a treatment envisioned by Angelakos himself and featuring the talents actor-director Peter Bodganovich. “It was kind of the most incredible experience I’ve ever had,” he laughs.

Four days later, Angelakos will post a brief, saddening message on his band’s website, canceling a string of upcoming tour dates in order to focus on “improving [his] mental health.”

On the day of our chat, when I first ask Angelakos what he’s been up to lately, he responds, “Lots and lots and lots of interesting, strange, odd, uncomfortable, fun, exciting things.” He isn’t kidding. Over the past couple years, Michael’s life has been a direct reflection of his bipolar syndrome, filled with extreme highs and debilitating lows: getting engaged, getting hospitalized, contemplating suicide, and—oh yeah—writing and recording Gossamer, one of the young decade’s most vibrant and densely layered pop albums.

Angelakos is a people pleaser. And like most people pleasers, he hates letting people down. That mentality can be a major problem when you’re a manic-depressive indie-pop icon with a huge fanbase—one that has certain expectations for what your music should sound like.

“There’s an anxiety involved with that,” Angelakos says. “You want to make everyone happy. I’m terrible about that—I just want to make everyone happy, say the right thing, do the right thing. If someone’s unhappy with me or somebody thinks I’ve done a bad job, I just feel utterly terrible.”

On Gossamer, Angelakos faced that classic dilemma that plagues every popular artist writing a sophomore album: whether to write for yourself or write for your now hugely-growing audience. Ultimately, with the help of Aldi and Zane, Angelakos was able to do both. Left to his own devices, the music Angelakos would’ve made probably wouldn’t resemble Passion Pit whatsoever.

Angelakos has suffered from Bi-Polar 1 disorder since the age of 18. He’s been hospitalized on several occasions throughout his adult life, including a now-infamous stint after his breakout performance at the 2009 South by Southwest Festival. But last year, Angelakos suffered an “episode” that nearly proved inescapable—one that nearly derailed him from ever finishing another song.

“I don’t know…something triggered the episode, and I started drinking,” Angelakos says. “And drinking exacerbates the effects of mania. And I think at the time, I was taking medication to get out of the depressive episode, and that launched me into the manic episode. What happened is I cut myself off from everyone, which is pretty standard. You become very…you just…you’re insane! You’re just not yourself. And I don’t really know how to explain it. I’ve obviously seen people in close quarters, but it’s different for each person, I guess. What happened for me is that I was drinking so heavily because it was acting as a compressor to help being me down from the insane overwhelming high of the mania. So I would have to drink extraordinary amounts of alcohol to combat this feeling. Mania is not fun. Mania is not fun at all. People think that it’s like when you’re creative—no. You’re creative when you’re maybe a little hypo-manic. That’s the best state ever—that’s amazing. But mania is completely debilitating, and I did literally nothing for about a month-and-a-half. I was verbally abusive to my friends and my fiancee. I didn’t know I was being this way, but it’s the truth.”

“This went on and on,” he continues, “and I was pushing people away and slowly filing through all my friends until they slowly started realizing I had a problem. And once they realized I had a problem, I would move on to the next person. So the alcoholism was just a way of dealing with and self-medicating the manic episode.”

When Angelakos eventually met up with Zane over dinner, these problems became magnified.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-