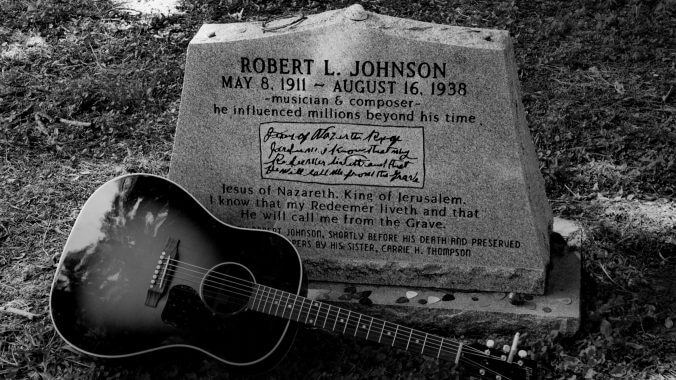

The Curmudgeon: What If Robert Johnson Hadn’t Swallowed That Poison Whiskey?

Photo by Robert Knight Archive/Redferns

Editor’s note: In the final paragraph of his August 25 story in Paste on the troubled folklorist Mack McCormick and his book about Robert Johnson, Geoffrey Himes wrote: “Now that the book and the field recordings have been released, we know more about Johnson and Texas blues, but we are still left with burning questions. The biggest question of all is what might have happened if Johnson’s life had not been cut so short and he had lived to become a crucial figure in the tumultuous changes in American music during the 1940s and ’50s. In a forthcoming Curmudgeon Column, we will try to provide an answer.” Himes makes good on that promise in the following piece of alternative history.

In 1938, many sources allege, the blues singer Robert Johnson was playing in a juke joint near Greenwood, Mississippi, when a jealous husband handed the musician a flask of tainted brown liquid. Within hours, Johnson was doubled over with stomach cramps. By dawn, he was dead. But what if Robert Johnson had never swallowed that poisoned whiskey? What if this had happened instead? Robert Johnson lifted the unlabeled glass bottle to his lips, but Rice Miller knocked the drink out of his partner’s hand. “Don’t ever take a drink if you don’t know where it comes from,” Miller barked.

“Don’t ever knock a bottle out of my hand,” Johnson retorted. Soon, the two musicians were pushing each other around the cramped juke joint, about 15 miles from Greenwood. It was August 15, 1938, a dangerous time to be Black in Mississippi. If Joe Turner (aka Joe Turley), the Tennessee prison warden, didn’t get you, a jealous husband would. A heavyset young woman jumped on Miller’s back to pull him off Johnson. The woman’s husband yanked her arm and pulled her off. An orange-and-gray cat was licking up the spilled whiskey.

The juke joint owner came up with a baseball bat in his hand and growled at the fighters, “Your break is over. Get over there and play some music.” Still seething, his pinstripe suit rumpled by the tussle, Johnson was in no mood for the Ink Spots, Gene Autry and Jimmie Rodgers songs he’d sung in the previous set. Now, he wanted to play songs of anger and dread, desire and frustration, songs he had written himself: “Hellhounds on My Trail,” “Stones in My Passway” and “Crossroads.” His voice sounded as if he were ready to kill or be killed. His guitar and Miller’s harmonica seemed to be continuing their battle with different weapons.

From his chair by the potbelly stove, Johnson could see everyone in the jammed-pack room. He could see that woman, the one in the red dress who had taken him out in the cotton fields earlier that evening. He could see her husband in overalls thrusting another bottle toward him with a glare in his eyes. He could see that cat vomiting in the corner. He could see Miller shaking his head furiously as the bottle came nearer.

Johnson raised the palm of his left hand and pushed the bottle away. The man protested. Miller rose up out of his chair in response, and the owner reappeared with his baseball bat. “These days keep on worryin’ me,” Johnson sang icily, “there’s a hellhound on my trail.” Once the set was over, Johnson turned to Miller and said, “You were right, Rice; that man is out to get me. Let’s split.”

“Go get our money and I’ll stand guard till we can get away,” Miller replied. Johnson asked if they could bring the girl along, and Miller said, “Are you out of your fucking mind? It’s a wonder you ain’t dead already. Don’t you know you’re supposed to fool around with a married woman behind her husband’s back—not right in front of him?”

The two men made their way into the nearby piney woods and found a bed of needles where they could sleep. When they woke, as the first glimmer appeared in the East, Miller said, “We need to get going. Mississippi won’t be safe for a while.” Johnson asked if they should go to Memphis. “Naw, that’s too close,” Miller replied. “Too many of these Black folk got kin up there. Let’s go to Chicago.” They bushwhacked to Grenada Junction, where the trains slowed down at the switching yard. The two men hid in the weeds till a northbound freight braked enough for them to grab hold of a box car and swing inside.

Two days later, they were on Chicago’s South Side, a landscape as vertical as the Mississippi Delta had been horizontal. Disoriented by the tall walls on each side of the street, they tried to fill their empty stomachs with the money from their last gig. A diner waitress pointed the way to Maxwell Street, an open-air market where many street singers were trying to attract attention. The two newcomers found a gap between two competitors and started playing. No one paid them much mind until Johnson played the closest thing to a hit he’d ever had, the double-entendre car song, “Terraplane Blues.”

Some women came up and said, “I remember that song from down in ol’ Miss; a fella named Robert Something made a record of it.” “That’s me! That’s me!” Johnson cried.

“Ah, c’mon,” the woman said skeptically. “You don’t sound like that record.” “That was me,” Johnson repeated. “Tell her, Rice.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-