Here’s Why the Media and Its Pundits Get American Politics So Wrong

Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty

Self-described Democratic socialist Bernie Sanders is the first presidential candidate in the history of Democratic primaries to win the popular vote in each of the first three contests.

That sentence violates all the rules of conventional political wisdom—as does the existence of President Donald J. Trump—yet here we are.

In the wake of Sanders’ win in the Nevada caucuses, major media seemed to finally do some serious introspection over their pundits’ inability to discern what is actually going on in America. What is supposed to be taking place based on conventional wisdom is not happening and actually has not transpired at all in presidential elections this century.

America generally considers itself to be a center-right country, and you can find polling to back this up. Gallup asks Americans to describe our ideological views, and 37% classify themselves as conservative, 35% as moderate, and just 24% as liberal. These figures are the undercurrent fueling both conventional wisdom as well as the fear that Bernie Sanders cannot win the presidency in a country that has awarded most of its presidencies to George W. Bush and Donald Trump this century.

The problem with this assumption lies in the source of these polls. The methodology producing Gallup’s annual data is scientific, but the people creating it are not. One of the first lessons I learned studying political science is that average Americans are not accurate when describing their political ideology, and polls like that are very unreliable due to the fact that we are not a particularly well-informed populace. Just 12% of Americans say they have heard of Vice President Mike Pence. One study reveals that older people have a far more difficult time telling fact from opinion than young people do, but digging deeper into the study reveals that cable news consumption, not age, is the source of this dynamic. Which is a hint as to where the blame lies.

This political illiteracy isn’t our fault. Major media has admittedly failed to properly unpack modern politics. They missed Trump in 2016 and they missed Bernie’s rise in 2020. We’re also not taught this stuff in schools (if you ask George Carlin he’ll tell you this is all by design). Everything I know about politics comes from my political science major and my subsequent studies afterwards. Unless you specialize in this kind of thinking, you likely are never going to learn it in America.

America Is Far More Liberal Than We Think We Are

A 2017 study of the 2016 electorate by the Voter Study Group flips the conventional narrative on its head. The supposed notion that America is filled to the brim with fiscally conservative and socially liberal voters is belied by the results below. The bottom right quadrant in the chart below is filled with all the actual fiscally conservative/socially liberal voters in the 2016 election.

https://t.co/I2PePHWenxpic.twitter.com/4ZkBlcou0j

— Best Posts (@onlygoodposts1) February 4, 2019

The bottom left is comprised of folks who are both fiscally and socially liberal, the top left is fiscal liberals and social conservatives (the real swing voters according to this study), and the top right is the GOP’s conservative base. Juxtaposing those results with Gallup’s proves that only one of these assessments of American ideology can be correct.

https://t.co/SskA9Pr0jDpic.twitter.com/k3W0bDcBDj

— Best Posts (@onlygoodposts1) February 27, 2020

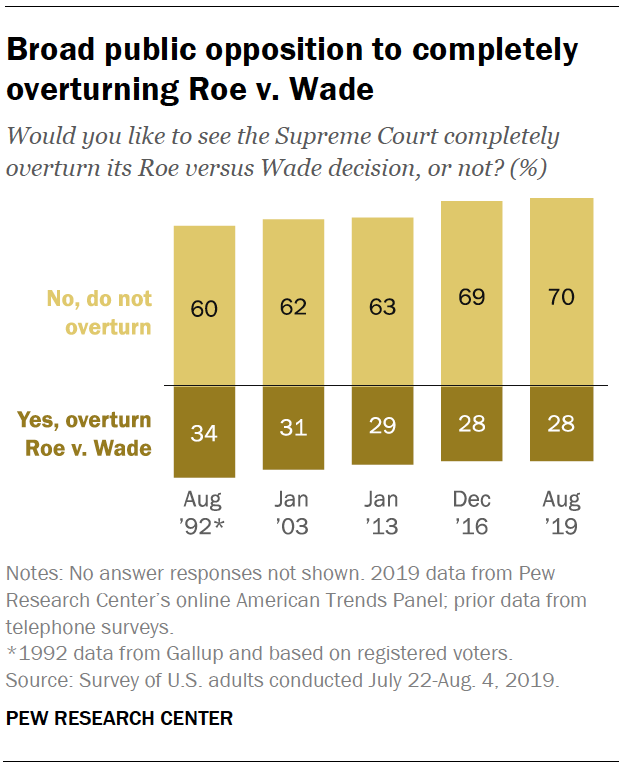

If we really were as conservative as we tell pollsters we are, you wouldn’t see broad majorities in opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade, which has been the conservative dream since the landmark case was decided.

American politics is a lot more complex than our aggressively simplistic left-right paradigm suggests. Under conventional wisdom, Bernie Sanders likely could not pull many votes from the Republican president, but based on this data by Voter Study Group, it is likely he would have captured a much higher share of the populist vote and beat Trump handily in 2016.

https://t.co/07luFnU7sqpic.twitter.com/yJ4gl1MqBg

— Best Posts (@onlygoodposts1) February 27, 2020

Further supporting the Independent Senator from Vermont’s case is this detailed piece in The American Prospect which highlights 48 poll responses where between 60% to 80% of Americans agree on various kinds of liberal beliefs. Here is just a sampling of what they found:

82 percent of Americans think economic inequality is a “very big” (48 percent) or “moderately big” (34 percent) problem. Even 69 percent of Republicans share this view.

78 percent of Americans say we need sweeping new laws to reduce the influence of money in politics.

60 percent of Americans believe “it is the federal government’s responsibility to make sure all Americans have healthcare coverage.”

74 percent of registered voters—including 71 percent of Republicans—support requiring employers to offer paid parental and medical leave.

63 percent of registered voters—including 47 percent of Republicans—of Americans favor making four-year public colleges and universities tuition-free.

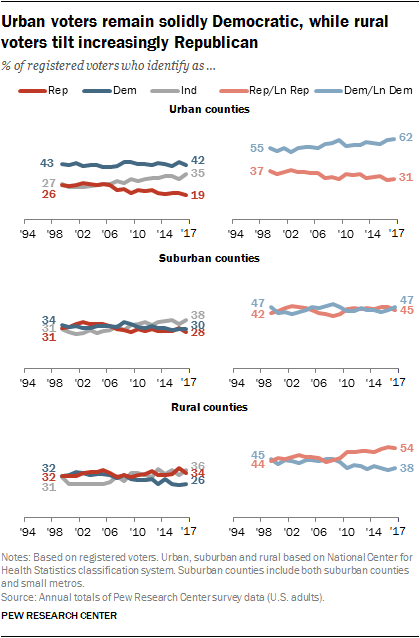

The split in our modern politics is a lot less ideological and a lot more cultural and geographical.

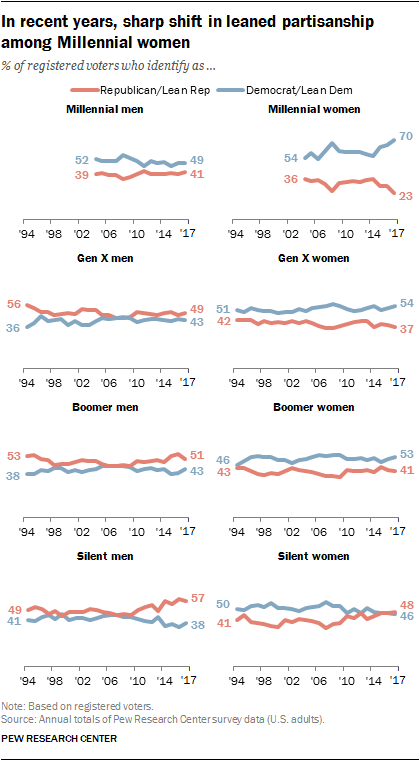

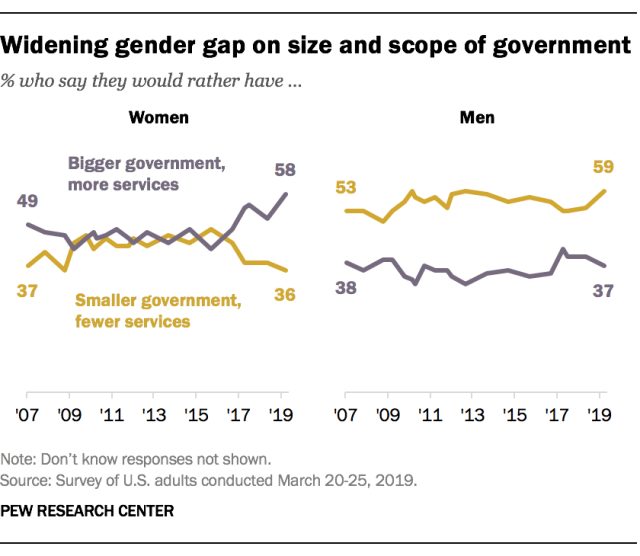

Additionally, if pundits are confused as to where this sudden rise of support for big government liberalism came from, the short answer is women.

What If I Told You Everything We Know About Elections Is Wrong?

What if there was no such thing as a swing voter? What if our two-party system’s electoral prospects are locked in well before either party has chosen a candidate? What if we are all powerless against the historical winds of change sifting our present into our past?

That’s the assertion put forward by Rachel Bitecofer, a political scientist at Christopher Newport University. She released a forecast in July of 2018 (before many primaries had selected a candidate) and missed predicting the November 2018 results exactly by one, so it’s a theory with proven merit. It was described as such in Politico:

Bitecofer’s theory, when you boil it down, is that modern American elections are rarely shaped by voters changing their minds, but rather by shifts in who decides to vote in the first place. To her critics, she’s an extreme apostle of the old saw that “turnout explains everything,” taking a long victory lap after getting lucky one time. She sees things slightly differently: That the last few elections show that American politics really has changed, and other experts have been slow to process what it means.

…

But even the more academic forecasts, like the polling models, are based on longstanding assumptions about why and how candidates win elections. And sometimes an event occurs that blows up those assumptions.

In 2017, Silicon Valley entrepreneur Peter Leyden wrote a compelling case for why California’s politics is always 15 years ahead of the country, and it buttresses Bitecofer’s case that we discount recent events far too much in our political analysis and place too much emphasis on inside baseball minutiae that ultimately adds up to small potatoes and is no match for the weight of history.

I took the notion of Bitecofer’s theory—that major events have the largest impact on who shows up for elections—and applied it to all American presidential history to see if any trends emerged.

Dear reader, they did. I did not put anywhere near the work into this that Bitecofer put into hers, so I hesitate to call my forthcoming analysis anything but a simplistic theory, but I think she’s definitely on to something significant. Generations rise and fall, heroic and/or calamitous events happen, and people either want change or not largely based on recent events. Drawing lines around major historical events and their influence on our two-party system reveals about seven eras in presidential elections.

1789 to 1828: The Founding Fathers

America was first ruled by those who helped write the rules. This is an era unto itself, and it is difficult to discern any modern meaning from their extremely segregated and antiquated elections.

1829 to 1860: The Primary Cause of The Civil War

This stretches from Andrew Jackson’s first term to the end of Worst President Ever James Buchannan’s presidency. The Democrats and Whigs wrestled control away from the founders on behalf of the Southern vision of the constitution during this time, and they expanded America more than the previous era that included the Louisiana Purchase. This rapid pace of change and heightened internal tensions culminated in the Civil War, then the election of Abraham Lincoln, the first Republican.

1861 to 1912: The Republican Era

This was the longest, most dominant stretch for a political party in American history. From 1861 to the end of William Howard Taft’s presidency in 1912, the Republican Party won the White House every year save for eight nonconcurrent years when America clearly had a love-hate relationship with President Grover Cleveland. If you think of political parties as something like brands whose recent histories determine their futures, it’s clear that the Republican Party won the trust of two straight generations traumatized by the Civil War. By the time we reached the 20th century, Lincoln had faded into the past, and the rules were about to change again.

1913 to 1932: The Era of Instability

Like that of the founding fathers, this era is something of an outlier. Defined by the First World War and the largest economic crash since 1873, the years overseen by Democrat Woodrow Wilson and three Republicans in Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover were rife with upheaval. The Republican Party still clearly maintained a branding advantage, as Wilson was just the second Democrat to occupy the Oval Office since the Civil War, but times were changing. The world had failed a generation, and an opportunity for ambitious reforms arose out of the victories won from the trust-busting Progressive Era.

1933 to 1968: The New Deal and Great Society

What the 52 year stretch of Lincoln-driven dominance did for the Republican Party’s brand, these 36 years in power did for the Democrats. This era was defined by two major wars (one successful, one not), and the kind of aggressive progressive policies that the Sanders wing of the party wants to enact. Franklin Delano Roosevelt proposed the Second Bill of Rights in 1944 and the end of the generation brought Lyndon Johnson delivering free healthcare to millions of seniors. The only Republican to win during this time was General Dwight D. Eisenhower who was aided by the rise of the Cold War and a disastrous Democratic contested convention (and even he instituted policies considered radical by today’s Democrats, like a 90% top marginal income tax). Because the only constant of American politics is change, the crisis created by the Democrat-led tragedy in Vietnam reached a fever pitch, and President Johnson withdrew from the race in 1968, throwing the Democratic Party into disarray and opening up a lane for an ascendant force in American politics.

1969 to 2008: The Law and Order Era

The reason why past Republicans are more like Democrats and vice versa is because of the shift in the electorate that occurred along with the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The modern Republican Party was infused with Southern Democrats and other assorted figures across the country who were opposed to the integration of black people into society, and Richard Nixon appealed to these folks with a “law and order” message that clearly did not apply to him or his friends. The criminality of Watergate opened a window for Jimmy Carter that quickly snapped shut once Ronald Reagan brought evangelicals into the GOP, and the only other Democrat elected during this time was a man who declared that “the era of big government is over” and signed a 1994 crime bill into law that is so destabilizing it is still impacting the 2020 election. George W. Bush oversaw the downfall of the law and order era, as the financial crisis removed all pretense that kind of stuff mattered to those in power and the Great Recession severely damaged the Republicans’ brand as the party most trusted to provide the economy with a safe harbor.

2008 to Present: The Big Government Celebrity Era

Our modern political era began sometime around the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the 2008 crisis, as both events exposed the greed intrinsic to our banking and politics. These events destabilized both parties to the point where candidates deemed unelectable by conventional wisdom proved otherwise, and the most conventionally electable candidates have lost in every election this century. Both Barack Obama and Donald Trump promised more government intervention to a voting public demanding a deviation from our current calamitous course, and it’s early, but Bernie Sanders is beginning to follow in their same footsteps in promising an aggressive shift away from the status quo.

If True, What Would This Theory Mean for 2020?

That the Democrats will win the presidency, likely no matter who the candidate is. This is what California’s past, my simplistic theory and Bitcofer’s complex model all point towards.

The notion here isn’t that the winds of history automatically decide elections—as these same conditions existed four years ago—but that they have more influence on attracting certain voters to the polls than candidates and platforms do. The glaring hole in this theory is 2016, where the Democrats ran a particularly weak candidate who failed to capitalize on the dissatisfaction and desire for change brought by the collapse of the previous era. Every era defined by one party’s dominance still included one or two presidents from the opposing party, and it is quite possible that Trump is a historical outlier anyway. If this theory of historical winds being the strongest force for change is correct, then we are on the cusp of a prolonged stretch of Democratic White House occupancy so long as the party enacts a platform responsive to the wishes of its voters.

![]()

The ultimate lesson that all of us covering politics must take from the 21st century is that humility about what we don’t know is a prerequisite for knowing anything in the first place. It’s possible that every theory put forth above is wrong. It’s also possible that they’re right but pointing in the wrong direction, and Trump and the Tea Party are the enduring legacies of the Iraq War and Great Recession. The only certainty that we should have about modern political thought is that Carvellian 20th-century wisdom is useless in a time defined by presidents and popular movements whose very existence violates its rules. An open and active mind is vital to understanding America’s changing political winds being driven by women, the two largest and most liberal generations in history, and perhaps even by history itself.