Medical Transphobia, Queer Online Communities and Celebrating Life Through Protest

Image via Elie Gill

It seems wrong to remember a powerful, joyful person, with sadness. Hayden Muller was the first non-binary person I met. Sometimes I think I see them around town. It’s been three years. Like many trans people, Hayden should be alive today, but isn’t.

As a bisexual, I’m defacto closeted, but I’m part of a community of extremely-online Montreal queers: Canadians from all over the country, refugees, immigrants, and allies. We often didn’t meet each other in person for a long time, if at all. We met in meme groups like “Sounds like someone is being unnecessarily divisive on the left”, where we joked and commented, or on a number of community groups that tie Montreal anglophones together: Freakfam Jobby Jobs, Planting Zone, Chez Queer.

If you met in person, it might be at a potluck, a punk show, a lesbian mixer, your downstairs neighbor’s stick & poke party, a Marxist reading group, or handing out hot meals. But these were the people who stood beside me as we watched a Wobbly — a member of the International Workers of the World — confront a black SUV speeding towards protesters, on his own, during the march to commemorate Heather Heyer, who was murdered in Charlottesville, Va. with a speeding car. Our friend Hayden, also a Wobbly, was the one who everyone knew.

They helped us see what we could do for one another, and that we could ask for help. It’s standard stuff. You hear about friends working unpaid overtime in illegal conditions; you can’t make rent; you’re too sick to go buy groceries; you feel alone and dysphoric; your family disowns you; when your mental illness is getting the better of you and you don’t know what to do, when you’re dissociating, or being abused. The way our society is set up, these things are happening all the time, and it’s crushing to face these problems alone. And for queer kids, especially of color, especially gender minorities, being there for each other means everything.

Hayden showed us by example that we could join or form a union. We could text words of encouragement, accompany someone to their medical appointment, pick up groceries for them, pitch in for that rent check, do a friend’s dishes the day when they can’t get out of bed, just listen to them work through their feelings, give each other some grace, some mercy, be there, help out, stand up for one another, be each other’s family, celebrate our survival, say it’s going to be okay even if you’re not sure it is, joke around, bake a birthday cake, or hold someone accountable, with compassion. That’s mutual aid.

Media depictions of young queers often miss this, as if being extremely online means that we’re not part of the legacy of queer community stretching back through the AIDS crisis.

Their partner describes what happened to them; “Hayden had complained of symptoms for years but because of their chronic anxiety, their symptoms were chalked up to hypochondria, delaying diagnosis until their breast cancer had reached stage 3. Throughout their treatment, they were routinely misgendered and dead-named, and their treatment decisions were not respected due to their doctor’s ideas of what Hayden’s body should look like after surgery.”

Hayden’s lumpectomy did not succeed in removing all of the cancer. Hayden Muller died on September 7th, 2019. They had known for much longer than they let on, that their cancer was terminal.

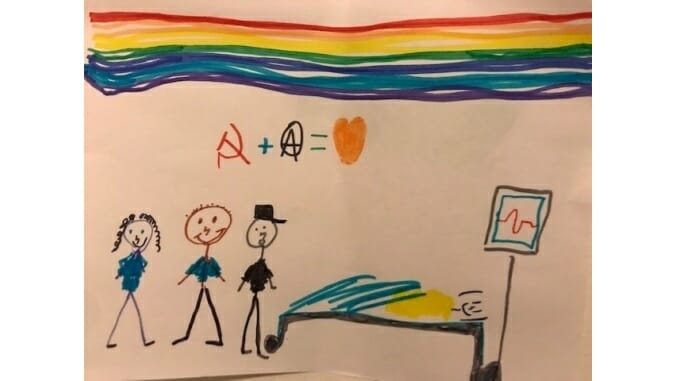

Their friend Izzy described their death, “Throughout the last days about a hundred people came by, huddled around Hayden’s bed to tell stories and say goodbye. People showed up with instruments, singing songs of solidarity. I like to think that in those last few days Hayden was dreaming of a better world.” Their memorial service was a march against transphobia in medicine.

Hayden Muller was everyone’s friend, so I’ll let their friends describe them. Carl, a non-binary trans activist and communist said, “Hayden was unforgettable.”

Kelly, a fierce and tender, high octane former goth, who introduced me to Hayden, said “They were one of the most beloved people I’ve ever known, and what I saw of their life and of their death unequivocally proved that.They believed in people. They looked out for people. I think they really wanted the best for everybody — well, except for flagrant capitalists, maybe! They were an example of a person who was able to stay tender-hearted in a world that does everything in its power to erode those qualities in people.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-