Please Cut Euphoria High’s Drama Budget

And use that money to hire Sam Levinson a writing staff.

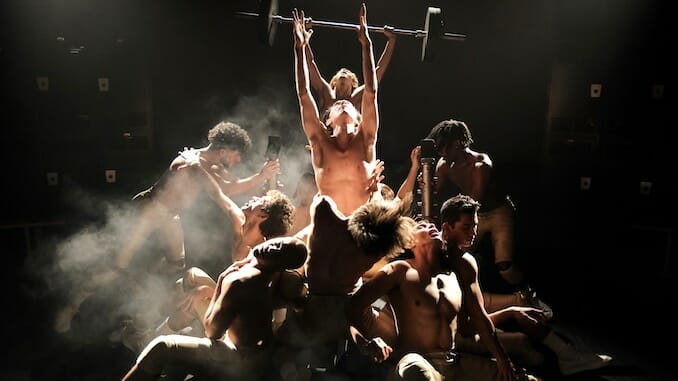

Photo Courtesy of HBO

I’ve seen worse plays than Lexi Howard’s. Hell, I’ve written worse plays than Lexi Howard’s, especially in high school. Thankfully, very few of my teenage plays were ever performed, and none of them were seen by an auditorium packed with my friends and peers. If they had, it would have gone down a lot differently than it did in the most recent episodes of Euphoria.

Tired of living on the periphery of the loud, explosive characters around her, Lexi has put on a play from her personal vantage point called “Our Life.” When the title is displayed onstage, spelled out in giant letters, it’s greeted with silence. Then there’s delayed clapping. Somebody drops a letter. Savour these moments, because it is the only instance where things feel like an actual high school play, with a bored audience and shoddy execution.

“Our Life” is obnoxious, obvious, and utterly devoid of substantial metaphor or meaning. This is excusable—to an extent. Lexi is a child and this is the first time her writing has been shared with an audience, even though this argument would be a lot more convincing if the play didn’t have the budget and backstage powers of an off-Broadway premiere. The play, and this moment, is the culmination of her ascendance from a paper-thin side character to a fully-fledged supporting role, one who is skeptical of her past (her troubles with watching addicts worsen their lives) and hopeful for the future (a sweet if ultimately doomed connection with Fez). But the weaknesses of the play aren’t acknowledged by the show; her anxieties about publicly expressing herself extend to, “Will it be too scandalous?” The problem is Euphoria treats “Our Life” like a powerful piece of art, so its attempts to reach emotional epiphanies for our characters fall drastically short.

The only reason Cassie, Maddie, Rue et al. are so affected by Lexi’s play is that it is literally their lives onstage. Scenes are directly lifted from their past and lit up with blaring spotlights, with the barest artistic interpretation or reflection gone into their staging. It’s an act of replication; the people in her life are given altered monikers and ushered out in front of an audience so Lexi can give us her opinions on them. When Cassie storms onstage, she sarcastically applauds her sister for just laying out all her trauma and expecting sympathy. As people boo Cassie, it’s clear where we’re meant to stand on this comment. But Euphoria’s writer intends for us to see something rich and powerful in “Our Life” in order to disagree with her.

Creator Sam Levinson (who has written all but one of Euphoria’s episodes by himself) is fixated with the idea that replaying previous beats from his own show will be hugely illuminating for his characters, but there’s very little to be gleaned from Lexi’s creative voice except for showing that she’s perceptive of her friends’ insecurities. One of the emotional cruxes for the play is just word-for-word Rue reading a speech she made at their dad’s funeral. Apart from the ethics of this (Lexi is lucky Rue was deeply affected by it), it is not good writing to directly transplant someone else’s emotional crisis for your own creative expression.

The finale sees a scene where Rue talks with Lexi about how “Our Life” finally let her look at herself in a way that was viciously self-critical, and how impressive she found the play.Before it’s confused by the reveal that it might have been the closing moments of “Our Life” (you could write a thesis on how Euphoria undercuts genuine emotion with stylised artifice), we feel that Rue, more than any other character, has been given a genuine insight into how she’s seen by others, untainted by her addiction. And yet, one gets the sense that the purpose of the scene was not to give emotional closure to two former friends, but that Levinson needed to spell out in dialogue a transcendent quality to Lexi’s play that wasn’t conveyed while it was onstage. (Unless this moment is also onstage! I’m exhausted.)

Apart from Rue, do the other characters featured in the play get access to another perspective on their lives? Are their values probed, challenged, is something about themselves revealed by how they react to what’s on stage? Cassie certainly feels slighted by her portrayal as the bratty, attention-seeking older sister, but there’s no reflection on this beyond her stagecrashing outburst (which was largely motivated by Nate), which just leads to her and Maddy catfighting. No resolution is offered to the sisters by the end of the episode, just as nothing substantial is also offered to Maddy and Cassie through the play.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-