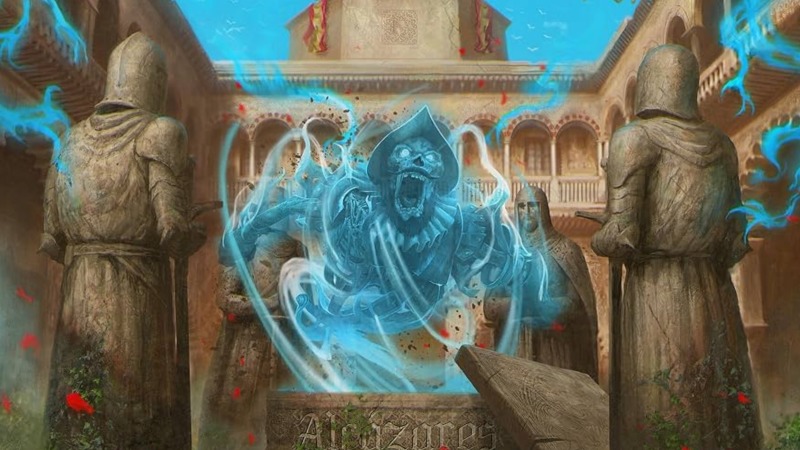

On Alcázares, Impureza Find New Ground In Metal

The Franco-Spanish outfit’s marriage of their roots and their interests fits naturally into metal’s evolution in the 2000s, and their third LP is a superb example of how the rest of us stand to benefit from metal’s global reach.

After 20 minutes of crushing, grinding, bruising, pulverizing metal on Alcázares, there is respite: “Murallas,” track six, where the Franco-Spanish band separates their sound and influences for a brief interlude rooted wholly in Spain’s aural culture. The Phrygian scales echoing in preceding songs take center stage, punctuated by snapping palmas accompaniment, with transportive effect. If you’ve ever been to Spain, and had the pleasure of hearing flamenco music played live while there, you might find yourself taking a trip through your memories, revisiting that time and place, as “Murallas” works its magic.

Then the track fades out, and the next, “La Orden Del Yelmo Negro,” commences with a tap-tap-tap from drummer Guilhem Auge, counting down the final moments of peace and quiet before cuing his bandmates. You are not on vacation; this is not Seville, Cádiz, or Granada, cities of flamenco’s birthplace, Andalusia. You’re certainly not in Orléans, Impureza’s home city, half a day’s drive and 700 or so miles away from the border Spain shares with France; Impureza sing entirely in Spanish about its history and rich culture, yet they live in its neighboring country to the north. (We’ll leave the full history lesson for another day, but you can thank Franco’s dictatorship for that.)

Anyone who’s followed the band since its inception in the mid-2000s knows all of this. But as Impureza develop their sound, their compositions, and their musicianship, the gap between where they’re from and what they sing about gains in relevance. Metal is a worldwide phenomenon. Truthfully, it always has been, despite class stereotypes that associate the average metal band as both belonging and appealing to coarser audiences situated in rundown urban America–a low-minded genre geared for low-income people. It’s nonsense, of course, because metal is for everyone, everywhere, and as that perspective gains increasing embrace, notions of what metal music can be, and how it can sound, expands likewise. Impureza’s marriage of their roots and their interests fits naturally into metal’s evolution in the 2000s, and Alcázares is a superb example of how we, the listeners, stand to benefit from metal’s global reach.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-