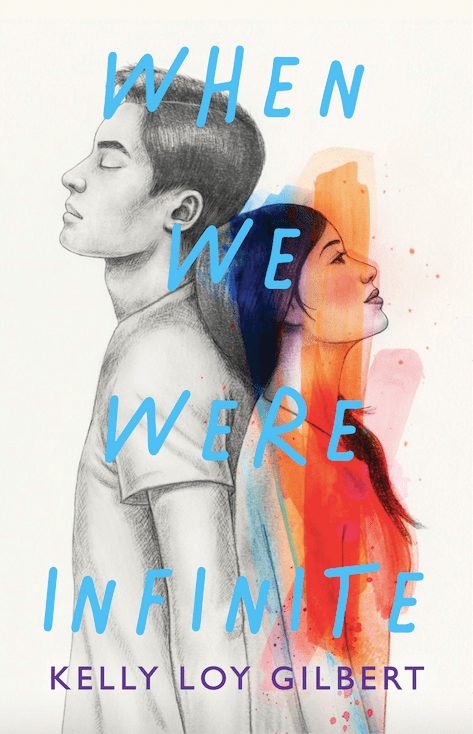

Exclusive Cover Reveal + Excerpt: Violence Rocks a Group of Teens in When We Were Infinite

Illustration by Akiko Stehrenberger

There’s a lot to love in every Kelly Loy Gilbert book. From Conviction, her stunning debut about murder, faith and abuse, to Picture Us in the Light, an authentic story of adoption and depression, she writes moving novels that are impossible to put down. Gilbert is known for tackling challenging themes with sensitivity, weaving narratives that will leave you shaken—in the best way possible.

Now the Morris Award finalist is back with a new Young Adult book that explores how a violent act rocks a group of friends. Here’s the description from the publisher:

All Beth wants is for her tight-knit circle of friends—Grace Nakamura, Brandon Lin, Sunny Chen and Jason Tsou—to stay together. With her family splintered and her future a question mark, these friends are all she has—even if she sometimes wonders if she truly fits in with them. Besides, she’s certain she’ll never be able to tell Jason how she really feels about him, so friendship will have to be enough.

Then Beth witnesses a private act of violence in Jason’s home, and the whole group is shaken. Beth and her friends make a pact to do whatever it takes to protect Jason, no matter the sacrifice. But when even their fierce loyalty isn’t enough to stop Jason from making a life-altering choice, Beth must decide how far she’s willing to go for him—and how much of herself she’s willing to give up.

Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers will release When We Were Infinite in October. We’re excited to reveal the beautiful cover and to share an exclusive excerpt below:

Cover design by Lizzy Bromley and illustration by Akiko Stehrenberger

Prologue

When Jason was voted onto Homecoming court the fall of our senior year, it both did and didn’t come as a surprise. It didn’t because Jason was attractive and talented and kind (I, of all people, understood his appeal); it did because he generally disliked attention and, for that matter, dances. And because I often thought of the five of us as our own self-contained universe, it was a little jarring to have the outside world lay claim to him like this. Netta Hamer, the ASB president, made the announcement at the beginning of lunch one day, when the five of us were all sitting together in our usual spot. We were, of course, as delighted as Jason was visibly mortified—he tried to pretend he somehow hadn’t heard, which meant that now we weren’t going to shut up about it—but we couldn’t have known then how that night of Homecoming would turn out to be one of the most consequential of our friendship.

“For the record,” Sunny said, “I do think it’s a tradition that needs to die, like, yesterday,” Sunny was the ASB vice president, which she’d described as the group project from hell. Associated Student Body officers ran all the dances, and Sunny had tried, unsuccessfully, to do away with the dance royalty. She had been on the Winter Ball court her freshman year, the same year as Brandon—in fact, since Grace had been on the junior prom court last, I was the only one of us five who’d never been chosen. “You parade around a bunch of random people and it’s just like, Hey, look at these people who haven’t even accomplished anything specific! And it’s so weirdly heteronormative.”

“Ooh, but I can’t wait to see Jason get paraded,” Grace said, clapping her hands. “Jason, do you get to pick out theme music? I hope they make you wear a crown.”

“Should I buy a new phone?” Brandon said thoughtfully, dangling his old one in front of Jason’s face. Jason kept eating, glancing past it into the rally court. “Will all the many—and I mean many—pictures I’m going to take fit on mine, do you think?”

Jason balled up his burrito wrapper and arced it into the trash can a few feet away, then pointedly checked his watch. “Oh, don’t be so modest,” Brandon said, grinning hugely, knocking Jason a little roughly with his shoulder the way boys did with one another—some boys, anyway, because I’d noticed Jason never did that sort of thing, even in jest. “You’re going to be so inspiring.”

“You know, honestly, I think it’s kind of nice,” Grace said. “Everyone here is too obsessed with accomplishment. It’s nice to have one thing that’s just like, You didn’t do anything to earn this! We just like you!”

“Mm,” Sunny said. “That’s a pretty idealistic way to say a bunch of underclassmen think Jason’s hot.”

Jason choked slightly on his water, but recovered. Brandon gleefully pounded his back.

“Little emotional there?” he said. “I get it, I get it. Big moment for you.”

“Jason,” Grace said, biting the tip off her carrot stick, “would you rather falsely accuse someone of cheating off you and they fail, or have every single Friday night be Homecoming for the rest of your life?”

“Oh, come on,” Jason protested, finally, “what kind of sociopathic choice is that?”

The rest of us cheered. “Put it up here,” Brandon said to Grace, lifting his hand for her to high-five. “You broke him.”

Would You Rather was Jason’s game. He used to come up with the questions when we were waiting in the lunch line, or walking to class: Would you rather badly injure a small child with your car, or have a single mother go to jail for hitting you with hers? Once Sunny had told me she imagined Jason played it alone, testing himself with all kinds of ethical dilemmas, which I believed.

We were all laughing. Jason said, “When I’m king and I’m looking over my list of enemies, I’m definitely remembering how none of you but Beth were on my side.”

Actually, I hadn’t joined in because I was imagining the night of Prom, how inside the music people would twine their bodies together and whisper secrets, how maybe on some certain chord Jason might look my way and want that with me, and I was afraid if I said anything now I might give myself away. I had been in love with Jason nearly as long as I’d known him. It was the only secret I’d ever kept from my friends.

I was about to chime in, though, when Eric Hsu came over. Later, after all the ways things came apart, I would look back at this moment as a warning, a kind of foreshadowing of what I let happen.

We mostly knew everyone in our class—we were a school of about two thousand and Las Colinas was always in the lists of top-ranked public high schools, which meant that years into the future we would still have a sleep debt and self-worth issues and nightmares about not having realized there was a back page of a calculus exam. Eric was the kind of person who would definitely pledge some kind of Asian frat in college, and Sunny and I had once clicked through his tagged pictures to confirm that he was in fact flipping off the camera in every one of them. (Also, he had the third-highest GPA in our class.) Eric’s eyes were bloodshot, and when he came close he smelled like pot. Jason cocked his head.

“You all right there?” he said. Jason had a way of being on the verge of a smile that made everything seemed like an inside joke you were in on with him. It made other people think they shared something with him, that they knew him well, although that usually wasn’t true.

“Yep. Yep,” Eric said. “Doing pretty good.”

“Yeah? What’s, uh, the occasion?”

“Just working on my stress levels,” Eric said. “We’re just all so stressed out all the time, you know?” Then, apropos of nothing, he turned and peered at me.

“Hey,” he said, “I want to ask you. How come you never talk?”

The five of us looked at each other. “Excuse me?” Sunny said, a little sharply. “What’s that supposed to mean?”

“Beth never talks to the rest of us. But then I see her sitting in your little huddle here and she’s all—” He mimed what I think was supposed to be mouths opening and closing with his hands. “How come?”

It was true that outside of our group I was much quieter. I’d overheard various interpretations about what my deal was: that I was boring, or stuck up, or a bitch. Still, what Eric said wasn’t the kind of thing people said to your face. It was jarring for a lot of reasons, but I remember it for one I wouldn’t have anticipated: how truly, utterly impervious I felt. Eric could say whatever he wanted about me. I was always invincible with my friends.

“You are high as fuck, buddy,” Brandon said, clapping Eric on the back, and there was an edge to his tone. “Maybe you should go home.”

“Well!” Grace said, when Eric had wandered off. “That was rude.”

I smiled. It seemed, at the time, like a small thing that would become one of our remember whens. But later it would feel like a relic from a different life, back when we could just root ourselves in the moment and not have to brace so hard against the future. And I would wonder if there had been signs I should’ve seen, even then, that could’ve changed how everything went after.

“I’m just not as dazzling as the rest of you,” I said, which felt true, but I didn’t mind. I knew from them how someone could shift through the wreckage of your life and pull you from the rubble as if you were something precious. That was worth being the least dazzling one—it was worth everything.

“Selling yourself a bit short there,” Brandon said. “I bet you could absolutely murder a crossword puzzle if I put one in front of you right now.” Since finding out a few years ago I loved crosswords, he’d always teased me about it. “If anything says dazzling, it’s absolutely crossword puzzles.”

“Beth, of course you’re dazzling,” Grace said.

“It’s fine. At least I don’t have to be on Homecoming court.”

Jason laughed at that. Later that day, though, as we were packing up after rehearsal, he turned to me.

“You know,” he said, “silence isn’t the worst thing in the world.”

He meant it kindly, in case I was still worried about what Eric had said, which I wasn’t. We were musicians; we were intimate with silence. Mr. Irving, who conducted the Bay Area Youth Symphony, or BAYS, as we called it, always said silence was sacred: it was in that space that whatever came before or after was made resonant.

And I had always known silence: as fear, first as that catch in my mother’s voice and my father’s stoniness in return, and later as all those throbbing empty spaces where he used to sit or sleep or keep his computer and his gaming things. I had known it as the possibility of emptiness, as something I was trying to shatter each time I picked up my violin.

There was so much the five of us had lived through together, so much we’d seen each other through. But in the whole long span of our history together, this was the most important thing my friends had done for me: erased that silence in my life. In the music and outside it, too, we could take all our discordant parts and raise them into a greater whole so that together, and only together, we were transcendent.

I always believed that, in the end, would save us.