How American Bourbon Whiskey Almost Disappeared Forever in 1968

This piece is part of a series of essays on alcohol history. You can read more here.

It’s easy to take for granted at this point the enduring popularity–the mania, really–of bourbon whiskey in the American spirits market. The last decade-plus has been marked by an explosion of consumer interest in bourbon that began with Pappy Van Winkle fetishism in the 2000s and gradually morphed to include an inexhaustible supply of so-called limited edition releases that now crowd the shelves at package stores. To those who discovered bourbon in the last decade, it likely feels like this obsession with American whiskey has always been there, that this is the natural state of affairs. Suffice to say: No, not really. Bourbon, like other spirits, has been through some great ups and downs over the decades (and centuries), seeing its popularity and cultural cache ascend to great heights and then come plummeting down. But there’s one point in particular in the late 1960s/early 1970s that could easily have irrevocably changed bourbon as we know it. Change this one thing–a change that the distilling industry was requesting at the time–and the entire bourbon whiskey renaissance of the 2000s likely never happens. It’s probably the biggest “what if” in bourbon history.

That one thing is the federal definition of “bourbon whiskey.” At the time, the country’s largest whiskey producers were petitioning the predecessor of the current Tax and Trade Bureau (the TTB), the Federal Alcohol Administration, in an effort to change what they could get away with calling “bourbon” or “rye whiskey.” If they had succeeded, the quality controls that had been in place since the start of the 1900s would have been upended, allowing an extremely questionable array of products to enter the market while being labeled as “bourbon.” But why did the distilleries want this in the first place? And how did bourbon manage to survive?

How the Bourbon Definition Protects American Whiskey

When we talk about the definition of bourbon, we’re talking about the same federal requirements you’re likely well familiar with, including the following:

— Bourbon must be made from a mash of at least 51% corn.

— Bourbon must be aged in new, freshly charred oak containers.

— Bourbon can be initially distilled to no more than 160 proof.

— Bourbon can be entered into its newly charred barrel for aging at a maximum of 125 proof.

— Bourbon must be bottled at a minimum of 80 proof.

There are additional terms, such as the “straight bourbon” designation, meaning other standards of quality have been met, “straight” implying a product that has been aged for at least two years, and often four or more (an exact age must be provided, if it’s under four). These rules were put in place at the end of Prohibition in the U.S. and mirrored rules previously established Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. And it’s important to note that the commercial distilleries supported the creation of these rules, as a means of legitimizing and enshrining quality guarantees in their business ventures, which were not always seen as upstanding professions. In particular, the creation of a high-quality definition for terms such as “bourbon” was important to distillers of the day because cheap, inferior “whiskey” was also being produced in bulk by rectifiers making industrial alcohol. Combine this potent, neutral grain spirit with some caramel flavoring and color, water it down, perhaps give it the briefest of aging, and you can definitely sell it as “whiskey.” Neutral grain spirits are still used in this way, in the making of cheap blended whiskeys sold in the U.S. But the bourbon term was meant to create a higher standard, one that the rectifiers couldn’t meet by including their neutral grain spirits in the blend. If you saw the word “bourbon,” you’d know that you weren’t drinking what was effectively colored vodka.

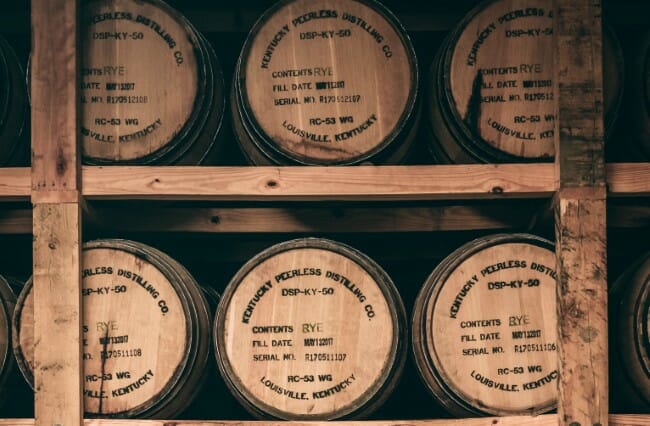

Making traditional bourbon is a process that demands time, and there’s no way to get around it.

Making traditional bourbon is a process that demands time, and there’s no way to get around it.

This is the case because of requirements such as the initial distillation to no more than 160 proof. It might be natural for a consumer to assume that distilling a spirit to a higher proof would yield a more flavorful liquid, but in reality the opposite is actually true. As initial distillation proof climbs, the ethanol in essence becomes more and more “pure,” stripping away more and more of the flavors created via fermentation of grains. By the time you get to 190 proof, you’re left with an almost perfectly neutral, tasteless spirit that just tastes like pure ethanol. But bourbon can only be distilled up to an initial max of 160 proof, meaning more of the delicate, grain-derived flavor compounds known as congeners are left in the spirit. In short, it’s a less efficient, but more flavorful process. The same is true of the maximum proof for entering a barrel–the higher the proof, the more bottles of liquor that barrel can ultimately yield when it’s proofed down to be bottled, but the less flavorful that spirit will end up being. Some modern distilleries in particular are exploring lower and lower barrel entry proofs to maximize flavor.

In the 1960s, on the other hand, American distilleries were petitioning the federal government to effectively throw that definition for “bourbon” in the trash.

Why Distilleries Wanted to Change “Bourbon”

The root of this desire to upend the definition of bourbon whiskey was a deep-seated fear in the American spirits industry about the effects of changing consumer taste and foreign competition from imported whiskeys that were seen as bourbon competitors. These fears manifested as the bottom fell out on American whiskey sales in the back half of the 1960s, following several decades of growth, leaving bourbon producers scrambling to point fingers and find solutions.

And to be certain, American drinking culture was changing during this time. In the postwar era, a new fascination with “easy” and “fast” products, brought to American culture by labor-saving technology and mass production, made uniform blandness something of a virtue for many rather than a detraction. The likes of Wonder Bread and microwave dinners were hailed as the future, and consumers increasingly expressed a desire for “lighter” flavor profiles in many areas, including spirits. This led to a problem of perception, in which spirits such as classic American bourbon or rye whiskey were being seen as old-fashioned and stuffy–aged rum suffered the same fate, which hurt tiki cocktail culture for decades–while “lighter” clear spirits such as vodka and gin were increasingly seen as modern and hip. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this period coincides with the beginning of what is considered a low point in American cocktail culture, as tastes became less complex and sophisticated.

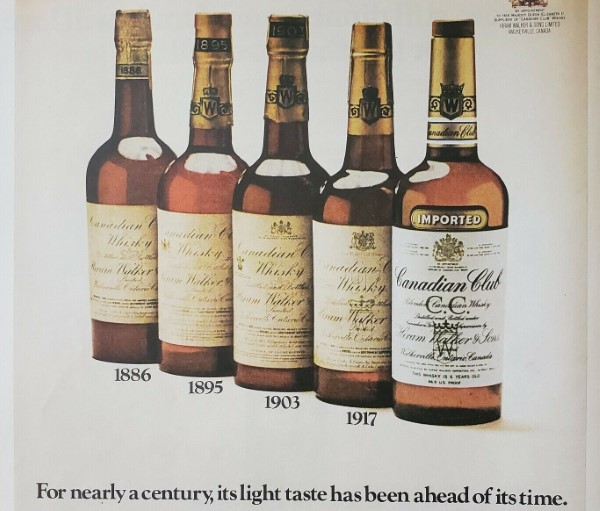

One area that was doing pretty well in the late 1960s/early 1970s, though, was imported whiskey, be it scotch whisky from the U.K. or increasingly blended Canadian whiskeys. And this makes thematic sense, because these regions were known for being able to produce “lighter” spirits, given that they were exempt from several of the key American provisions of the “bourbon whiskey” definition.

The “light taste” is a big selling point in advertising of the era.

The “light taste” is a big selling point in advertising of the era.

In countries such as Ireland, Scotland and Canada, distilleries could push initial distillation of a spirit as high as 190 proof, that spirit could enter the barrel at a higher strength, and the most commonly utilized barrels were re-used American oak that had previously matured bourbon. All three of these factors make for less expensive whiskey/whisky production, at least for the mass-market flagship brands, and they also make for products that read as “lighter” to the consumer in terms of their assertiveness of flavor. And with American distilleries convinced that these imports represented the tastes of the future, they wanted the opportunity to do the same thing … while still marketing that product as “bourbon.”

This was the issue, for the distillers: They were free to make a product containing distillate that was close to neutral grain spirits, but they didn’t want to have to call that spirit by a generic term like “whiskey,” or tell consumers on the label that a product was aged in re-used barrels. Instead, they wanted to change the definition of bourbon so it would fit the lighter spirits they wanted to make. In doing so, they wanted to subtly change the consumer’s expectation of what “bourbon” was supposed to be in the first place, gradually enough that the drinker would never realize that it had changed.

Suffice to say, this change proposed by multiple major industry distillers looks incredibly short-sighted and damaging in retrospect–distilleries looking to undermine their own quality standards in order to court what they perceived as changing tastes, in a way that could have unraveled more than a century of bourbon history and culture. If these proposed changes had been accepted by the Federal Alcohol Administration, it’s impossible to say how many major bourbon producers might have changed their recipes entirely, producing more neutral spirit or abandoning the practice of aging whiskey in newly charred barrels. Over the course of decades, this could have accelerated the pace of changing tastes, while older consumers who remembered “bourbon as it used to be” may have slowly dwindled away. It’s entirely possible that within a generation of the definition being changed, there could have been very little traditional bourbon whiskey being produced in the U.S. at all. And if that happens, it becomes extremely unlikely that bourbon (and American whiskey in general) would undergo its renaissance in the 2000s, ending up where it is today. We could have ended up in a market ruled entirely by cheap, blended whiskeys, unaware that traditional bourbon had ever existed.

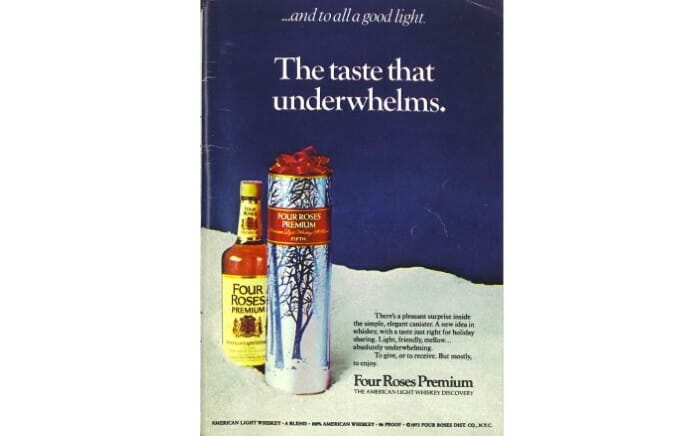

The “Light Whiskey” Alternative

Thankfully, this if course isn’t what ended up happening. Astutely judging that the requested changes to the definition of bourbon might be both misleading to the consumer and ultimately damaging to the category, the Federal Alcohol Administration rejected the industry’s proposals to change the “bourbon whiskey” definition in 1968. Instead, the agency created a new designation that was termed “light whiskey,” essentially giving the distillers a consolation prize to say “If you want to make this type of spirit, you can call it ‘light whiskey’ rather than ‘bourbon.'” These subsequent light whiskeys had more in common with the imported Canadian whiskeys they were competing against, although their marketing seems particularly ridiculous now, viewed through the modern lens of bourbon mania. Consider the Four Roses ad below, for instance, where the slogan “the taste that underwhelms” is being used as a positive selling point to market a less assertive, less strongly flavored spirit, and you can get a better idea of what a strange moment in history this truly was. It seems almost incomprehensible in comparison with the products that now command hype among whiskey geeks, which are almost invariably the strongest and most boldly flavored.

The American spirits industry of the time, however, had high hopes for light whiskey in the early 1970s when commercial examples began to flood the market. The category was projected to capture more than 10% of the U.S. distilled spirits market by the early 1980s, but this wasn’t to be–most of the brands performed relatively poorly, and before long they were being blended with more flavorful whiskey–such as traditional bourbon, in fact–to create the modern, cheap “blended whiskeys” that are still common on the bottom shelf of the package store today. As it turns out, although consumers of the time were indeed interested in lighter flavors and spirits categories such as vodka and gin, that didn’t mean they were also ready to ditch bourbon for less flavorful whiskey. The bourbon industry instead simply maintained a reduced profile through the next couple decades, before a new wave of innovation and product development in the 1990s began to set it on the path that would lead to its still-ongoing explosion.

Oddly enough, even light whiskey has managed to stick around for the ride, buoyed by the overwhelming popularity of bourbon, the very category it was more or less initially conceived to replace. Today, premiumized light whiskey expressions are increasingly common, with some well-aged sourced bottlings–most from MGP of Indiana, which has large stores of mature light whiskey–selling for hundreds of dollars. Without bourbon hype normalizing the idea of American whiskey selling for those kinds of prices–for better or worse–such a thing would be laughably impossible.

And yet, a single decision in 1968 could potentially have undone it all, leaving modern drinkers to a liquor market in which traditional bourbon would have been like a campfire story kept alive only through the oral tradition. Whiskey fans everywhere should be thankful we didn’t live to see that day.

Jim Vorel is a Paste staff writer and resident alcohol geek. You can follow him on Twitter for more drink writing.