Cocktail Queries: What’s the Deal with Pot Still Bourbon?

Photos via Unsplash, Martin Martz

Cocktail Queries is a Paste series that examines and answers basic, common questions that drinkers may have about mixed drinks, cocktails and spirits. Check out every entry in the series to date.

When approaching the question of “why does bourbon taste like … bourbon?” in the abstract, it’s a launching point for a topic that can be explained relatively simply, or in exponentially more complex terms, the more detailed you want to get. For the average rank-and-file consumer, though, some aspects are likely to be much better understood than others. The effect of a newly charred, white oak barrel, for instance, is rather easy for the average consumer to grasp: It imparts color and assertive flavor to newly distilled whiskey. So too can the typical drinker pretty quickly understand the impact of mash bills, and the difference in flavor inherent to grains such as corn, rye, wheat and malted barley. But more likely to be misunderstood are the finer points of distillation itself, and how this step ultimately impacts what you’re drinking, starting with the most basic question of all: What kind of stills are being used? For the vast majority of bourbons, “a column still” would historically be the answer, but with the rise and steady maturation of the craft whiskey/microdistillery world, pot still bourbon is becoming increasingly common and accessible. But what does this mean, really?

That’s a complex question–more complex than it seems, even to those with a basic understanding of professional distillation. But suffice to say, bourbon whiskey produced via different types of still can present with radically different characteristics. And in a scene with more distilling entities than ever–and more sourcing and blending than ever–pot still bourbon can increasingly find its way onto shelves even when it’s not the sole liquid in a bottle. Here, we’ll dive into what makes those bourbons unique, and why you’re more likely to run into them now than ever before.

A Primer: Pot Stills vs. Column Stills

The pot still is a device with a sprawling, lengthy history that goes back many centuries. They’re essentially the evolved version of the first-ever alchemical devices used for distillation, the alembic still. Distillation of alcohol on these devices for medicinal and scientific purposes became established during the Medieval period, but it wasn’t until the 1600-1700s or so that access to those stills became widespread enough to see a flourishing of commercially available brands of spirits such as gin, brandy and malt whisky. Perhaps unsurprisingly, some consumers were not at all ready for this sudden influx of affordable, potent ethanol, resulting in public health crises such as the Gin Craze in 1700s England. Regardless, the pot still became the de facto way of making distilled spirits.

This began to change via the commercial introduction of the continuous, or column still, in the first quarter of the 19th century. Scotsman Robert Stein’s initial column still design was famously improved upon by Irishman Aeneas Coffey, whose name is still lent to many “Coffey” column stills today. These tall, vertical stills didn’t need to produce singular batches of spirit one at a time like pot stills–instead, they could be fed a continuous inflow of fermented mash, and produce a steady stream of distilled spirit at a significantly higher level of potency in a single distilling run. In short, column stills were much more efficient at producing ethanol, but this isn’t the only factor that distillers had to consider.

Although the column still could produce a more pure, concentrated spirit with less time, labor and cost, there was a trade-off in terms of flavor and aroma. The spirit produced by column stills was generally more pure and potent, but in the process of distillation it also stripped away more oils and “congeners,” a catch-all term for trace chemicals produced in fermentation that give the spirit many of its signature flavors. This makes for a “lighter,” more neutral spirit. Pot stills, in comparison, produced a less potent spirit (often requiring two or more distillations), but left more of those congeners in the distilled product. This resulted in a spirit that distillers referred to as “heavier,” because it typically possessed more robust flavors and mouthfeel.

The two types of still, therefore, have continued to exist side by side ever since, with some being seen as integral to making specific styles of spirit. In Scotland, for instance, malt whisky is traditionally produced in pot stills, but grain whiskies (anything other than malted barley) are often produced via column stills, with the two styles frequently blended together. In Mexico, almost all tequila is produced via double distillation in pot stills, while in the Caribbean both pot stills and column stills are frequently used by the same distilleries in rum production, in order to yield both more bombastic/funky pot still rums and lighter, cleaner column still rums. Other spirits such as vodka and gin, meanwhile, are pretty much universally produced via column stills around the world, because the goal is to make as neutral a spirit as possible.

But what about bourbon?

Bourbon and the Pot Still

The rise of the column still in commercial spirits production correlates pretty perfectly with the advent of the American whiskey we today refer to as bourbon. Whiskey, of course, had been produced in the U.S. on pot stills from long before the American Revolution, being made from grain such as rye and then corn. None of it bore much similarity to modern bourbon, though, because the practice of aging that spirit in newly charred oak barrels didn’t begin to catch on until the early 1800s. And around that same time, the column still was also being widely introduced, ultimately becoming the de facto style of still being used in American distilleries producing bourbon whiskey.

Today, we associate the “classic” flavor profile of bourbon with a spirit produced on column stills, then aged in newly charred oak. This spirit retains a relatively lower level of grain-derived congeners, and subsequently gets a lot of its flavors from the barrel itself. On a distillery tour, you may hear a guide say something like “80% of the flavor of bourbon is derived from the barrel”–this isn’t exactly a scientific measurement, but a colloquialism to explain the importance of oak in producing bourbon.

There’s no reason, however, why you can’t take a classic bourbon mash bill (at least 51% corn) and distill it in a classic pot still instead. The resulting spirit tends to be notably viscous and oily in texture, with a high level of residual sweetness and strong fruity/grain-derived flavors that otherwise would be lost in column distillation. It’s important to understand that this is a “more flavorful” spirit in a technical sense, but that doesn’t mean it’s automatically preferred by consumers. In reality, pot still bourbon tends to be–in my experience, anyway–a rather divisive flavor profile. Many consumers are simply used to bourbon as they know it, and don’t care for the profile that a pot still brings to a corn, rye and malted barley mash. In particular, the “grainy” flavor that often comes through even in well-aged pot still bourbon has a tendency to make tasters believe that the spirit may be “young” or immature, because those flavors are often associated with inexpensive traditional, column still bourbons that have seen relatively little aging. In short, the flavor of pot still bourbon tends to be something of an acquired taste that some whiskey geeks adore, and some dislike.

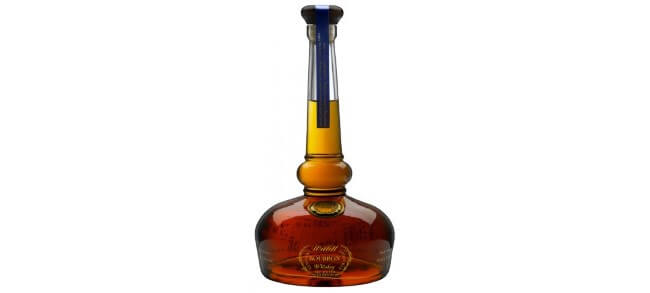

This has led to a somewhat complicated relationship between American bourbon producers and the pot still. There are some small distilleries that use pot stills for all of their spirits, including bourbon, but don’t necessarily call attention to this fact. They may reason that the general American whiskey consumer isn’t necessarily interested in pot still bourbon, or perhaps that consumer thinks they won’t be interested in it, so it’s better not to note this particular detail on their bottles. But at the same time there are other products such as the famous Willett Pot Still Reserve, that put “pot still” right in their name and have a bottle shaped like a literal pot still, but are reportedly initially distilled on a column still instead! This certainly feels deceptive on some level, and likely to influence the consumer’s perception in a potentially damaging way, but Willett has never revealed any concrete information on how exactly that brand (which has also changed several times over the years) is produced. But it goes to show how confusing the use of pot stills within the bourbon world tends to be.

Seriously confusing, when the entire brand is pot still themed.

Seriously confusing, when the entire brand is pot still themed.

Then there’s the use of pot still bourbon as a blending agent, where it is increasingly combined with column still bourbon. This is famously done by Woodford Reserve, a company that uses its copper pot stills as a symbol of the distillery. They don’t, however, release that bourbon directly: Instead, it’s reportedly blended with a large amount of traditional, column still bourbon from parent company Brown-Forman. They also distill that spirit on their pot stills three times rather than two, yielding a more concentrated spirit that is further away from a straightforward “pot still bourbon.” This style of blending is being practiced by a number of companies such as the likes of Bardstown’s Preservation Distillery, which is distilling small pot still bourbon batches and then blending them with sourced column still bourbon. They reportedly intend to release pot still-only batches in the future, once they’ve aged sufficiently.

The place you’re actually more likely to encounter modern bourbons made on pot stills is in the craft whiskey world. Here, companies such as Boulder Spirits (Colorado), Copper Fox Distillery (Virginia), and Spirits of French Lick (Indiana) are examples of companies that primarily are offering bourbons made exclusively via pot stills.

With that said … things can never be that simple, can they? The fact of the matter is, at the end of the day, even the “pot stills” being used by someone in the U.S. to distill bourbon may be physically very different from the pot stills being used in the Caribbean to make rum, or in Scotland to make malt whiskey. Some U.S. bourbon producers have completely custom stills that conceptually fall between pot stills and column stills, and a prolific still manufacturer such as Vendome Copper & Brass Works in Louisville will produce many unique hybrids for individual clients, allowing machinery to function as a pot still, column or something decidedly in between. You can even put a column rectifier on top of a pot still that can produce a much more concentrated/pure spirit in one run, sharing characteristics of both pot and column stills. What does one label the spirit coming from such a device?

As is the case of so many topics in this field, it’s a matter of “the more you learn, the more you realize there is to learn.” The general idea of “pot still bourbon” represents an interesting little niche within the larger bourbon whiskey world, one that we are seeing explored more often and integrated into the mainstream with increasingly well-liked results. It may be that in the coming years, a more recognized market for genuine pot still bourbon will begin to develop, though “genuine” is the sort of thing that will always require air quotes. Regardless, if you’re a bourbon geek, it’s an intriguing frontier that you may not have yet explored, and one that I would recommend checking out.

Jim Vorel is a Paste staff writer and resident liquor geek. You can follow him on Twitter for more drink writing.