The 2023 Holiday Gift Guide for Movie Lovers

As the 2023 holiday season approaches and the post-Thanksgiving sales of Black Friday and Cyber Monday hit, now is the perfect time to figure out what gifts to get the movie lover in your life. The Paste movies team is here to make life easier with our 2023 Holiday Gift Guide, highlighting the best potential presents ranging from exhaustive box sets of action movies to books on Beatles films to Werner Herzog’s new memoir. Heck, we’ve even thrown in a few subscriptions too — we’re hooked on magazines and streamers here too.

Here are the best gifts for movie lovers, 2023:

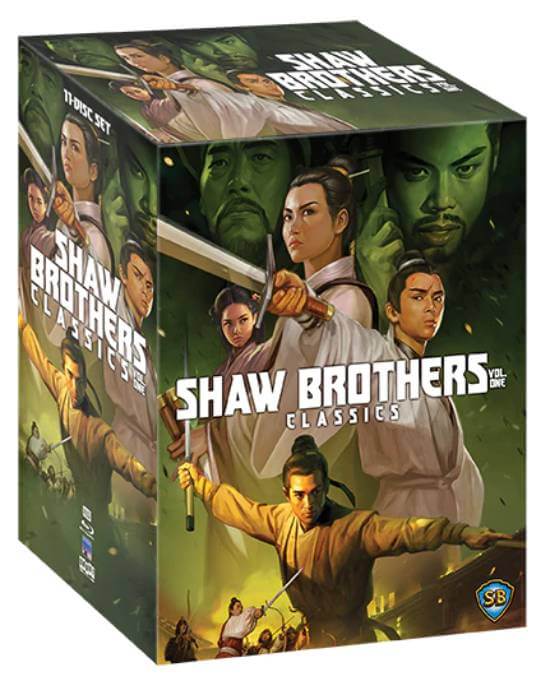

Shaw Brothers Classics: Volumes 1 – 4

Shout Factory’s massive collections of action movies from the legendary Hong Kong production company Shaw Brothers Studio cannot be oversold. Each volume (their fourth released this year) offers a dozen discs composing almost 20 hours of kung fu goodness, featuring films like 1968’s Killer Dart that have flown under the radar in America for far too long. Filled with audio commentaries that offer context for even the most obscure title, there’s no better way to immerse yourself in a classic genre — and experience the sheer dominance of the Shaw Bros. If you want to become an expert on the era, sate your unending thirst for martial arts madness, or simply log a few movies on Letterboxd that’ll be the envy of your peers, you cannot go wrong with one of these beautiful box sets.–Jacob Oller

Tokyo Pop – Kino Lorber Blu-Ray

How easily is it to balance blossoming romance with the anarchic souls of punk, heavy metal and rock ‘n roll? Where does the space exist for these dueling components to harmonize? Apparently, Tokyo; Fran Rubel Kuzui’s 1988 musical romantic comedy Tokyo Pop puts these unlike things together with such breezy tenderness that she makes the central challenge of making attitude, hallmarks of these related but separate music genres, just a moment in time. Characters curl their lips and thrash on stage in one scene but pour out their hearts to each other the next, without contradiction in tone. The percentage of cinema lost to institutional carelessness and time is hard to measure, so the preservation of Tokyo Pop comes as a miracle, because even small, unassuming independent films about a bleach-blonde American singer and a shaggy Japanese rock-obsessive deserve saving. In this particular case, the restoration functions as an in memoriam, too; Carrie Hamilton, who played the American, died in 2002 at age 38, with a short list of credits to her name, the Fame TV series and Tokyo Pop among them. Hamilton’s Wendy starts the movie in NYC, where she’s passed over for singing parts by her lousy rock band frontman boyfriend in favor of another woman, and immediately cuts ties and runs to Tokyo, where a friend’s standing invitation is supposed to provide accommodations. But shortly after landing, she finds out that her friend moved out of the country, leaving Wendy to fend for herself in a hostel decorated as a shrine to Mickey Mouse, one of many American imprints on Japanese culture Kuzui makes note of throughout the film. A Dunkin’ Donuts here, a KFC there, and vibrant rockabilly activity seemingly all over the damn place, which is how she meets Hiro (Yutaka Tadokoro). Hiro’s a charming scoundrel. On their first encounter, he tries to bed her in a love hotel on a dare by his bandmates and pals, which goes about as well as an instance of mixed messages and miscommunications abetted by language barriers can go; Wendy bites his head off and sleeps in the tub, with Hiro left to cram himself on the couch. Tokyo isn’t small, but Wendy and Hiro’s chosen subculture is; inevitably but not improbably, they bump into each other again, with a happier outcome. They become friends. They become an item, too, as well as partners in rock ‘n roll, because Hiro and his buddies know that having a towering blonde gaijin on vocals can only be good for their career. What Tokyo Pop never allows is overcooked drama where the couple has to decide if they’re really in love, or if they’re just trying to hit it big. The film is genuine. It devoutly avoids putting on airs. The combination of free-spiritedness, musical fellowship, bemused culture comedy, and kindred hearts is seamless, paced with the sense that Kuzui has somewhere to be and a clear path to get there; Tokyo Pop moves briskly, a quality enhanced by the liveliness baked into Hamilton and Tadokoro’s chemistry. But the breeziness carries bittersweetness, too, the kind that weighs the heart down without smothering the high of falling in love in the first place. It’s a remarkable effect. We should all be thankful to feel it in our own lives, much less in theaters.–Andy Crump

Close to Vermeer – Kino Lorber Blu-Ray

While Johannes Vermeer, the Dutch baroque master who painted some 30-odd works during his career, is generally considered an enigmatic figure in the art world, curators and experts have nonetheless dedicated their entire careers to evaluating his comparatively limited oeuvre. Thus, Gregor Weber, a highly-regarded expert on the artist, considers the “crown jewel” of his career to be overseeing the largest and most encompassing Vermeer exhibit ever at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. The planning and execution of this Vermeer retrospective is the focus of Suzanne Raes’s documentary Close to Vermeer, which unfurls into an engrossing 79-minute exploration of the experts, museums and debates that continue to engage with the artist and his legacy. Just a year away from retirement, Weber embarks on a quest to acquire as many Vermeer paintings as possible for the swiftly-approaching exhibit. Despite being a Dutch artistic icon, many of Vermeer’s works – including recognizable artworks The Milkmaid and The Art of Painting – are currently (and perhaps forever destined to be) part of permanent collections at foreign museums. As such, he and several Rijksmuseum colleagues, including fellow Vermeer historian Pieter Roelofs, attempt to secure loans of those paintings. They travel to The Frick and Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, Germany’s Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum and even the neighboring Dutch Mauritshuis museum in The Hague. When able to secure pieces for the exhibit, researcher and conservator Anna Krekeler puts them under her microscope and relishes in the details of Vermeer’s brushwork up-close. Though much of the doc’s beauty clearly stems from the gorgeous details inherent to the 17th century artist’s motifs, the overall momentum of the film is driven by art-world politics that typically don’t filter down into public consciousness. For example, a standoff of sorts develops when American researchers decide to disavow a work long considered to be an authentic Vermeer due to the predominance of a green hue in a subject’s flesh tone. Weber contests this finding – but is it due to genuine scholarly disagreement, or because he’s down to the wire in terms of making decisions for the Rijksmuseum exhibit? Pleasant and contemplative, Close to Vermeer chronicles an exhibit of a master that both civilians and historians know startlingly little about, considering the profound impact he’s had on the craft of painting.–Natalia Keogan

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-