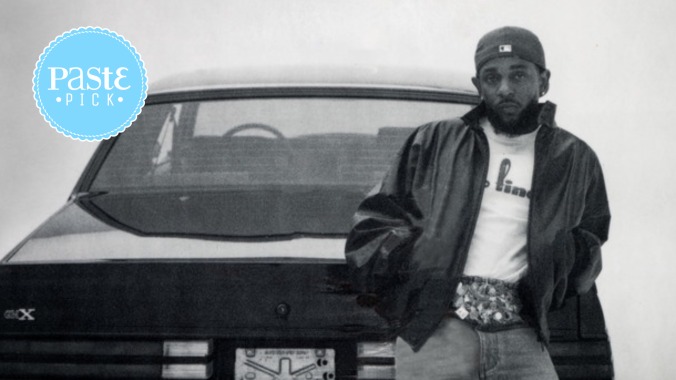

Kendrick Lamar Reimagines Rap’s Future and Reckons With His Past on GNX

The Compton rapper’s masterful sixth LP is a surreal, hypnotizing, danceable trip through a hip-hop prophet’s own ego death and immediate, braggadocious, finessing renewal.

It could, and should, be argued that the definitive artist of 2024 has been Kendrick Lamar—not Charli xcx, or Billie Eilish, or Sturgill Simpson, or Taylor Swift, or even Tyler, The Creator, who just dropped his latest epic earlier this month and paid homage to K.Dot in the process on “Rah Tah Tah.” With a Super Bowl halftime performance coming in early 2025, Lamar reinvigorated a listless culture at the coda of spring with a month-long avalanche of gutting, bloody blows directed at one of its kingpins, Drake. Then came the think-pieces and the taking sides of it all, as the two hip-hop giants turned an industry inside out with a beef so poisonous that it called to mind the greatest rap feuds, like Ice Cube versus N.W.A., East Coast versus West Coast, Eminem and 50 Cent versus Ja Rule and Kurupt versus DMX. No moment between Drake and Kendrick Lamar’s feud reached a high quite like “Hit ‘Em Up” did when 2Pac and the Outlawz dropped it in June 1996, nor was it as immediately consequential, but their beef wasn’t just a spectacle—it was a lesson in context, and a necessary prelude to considering Kendrick’s new album, GNX, which he dropped without warning at noon ET on Friday, November 22nd.

Kendrick and Drake have worked together here and there for more than a decade, beginning with the “Buried Alive Interlude” on the latter’s Take Care in 2011 and “Poetic Justice” on the former’s good kid, m.A.A.d city a year later. In 2023, J. Cole said he, Drake and Kendrick were the “big three” in the rap game. In March 2024, Kendrick responded via a verse on Future and Metro Boomin’s “Like That” (“Motherfuck the big three, n***a, it’s just big me”). A beef commenced shortly after between the three before Cole smartly dropped out and let Kendrick and Drake trade daggers. Drake released “Push Ups” and “Taylor Made Freestyle,” the latter using AI-generated vocals from Snoop Dogg and 2Pac, a move that prompted 2Pac’s estate to step in and demand the song be taken down from all streaming platforms.

But let’s be honest, the beef didn’t begin until Kendrick entered the chat. He dropped “euphoria” on April 30th and then, less than a week later, put out “6:16 in LA,” which Drake responded to, in a matter of hours, with “Family Matters”—a track that alleging that not only is Kendrick Lamar a domestic abuser, but that one of his kids was fathered by former Top Dawg Entertainment CEO Dave Free. It only took an hour for Kendrick to hit back, putting out “Meet the Grahams” and accusing Drake of sex trafficking, fathering a second child in secret (a déjà vu moment, calling back to Pusha T’s bombshell diss track against Drake that revealed the identity of his secret son, Adonis) and being a sexual predator.

If that wasn’t enough, Kendrick responded to his own song with “Not Like Us,” which accused Drake of pedophilia and shot to #1 on the Hot 100 chart—joining the ranks of “You’re So Vain,” “Hollaback Girl,” “Bad Blood” (featuring Lamar), “good 4 u” and the aforementioned “Like That” as diss tracks that became hits. It was glorious, surreal and galvanizing. When Drake tried responding with “The Heart Part 6” days later, there was no reputation left to salvage or momentum left to flip. The OVO leader was nothing more than debris collapsing beneath Kendrick’s probable desolation. But let’s back up a few years.

In 2022, Kendrick Lamar returned to the spotlight with his much-anticipated, long-awaited DAMN. follow-up: Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers. The record was a polarizing feat of anti-role model language; a takedown of the legacy everyone else built for him in the wake of To Pimp a Butterfly’s global and critical success in 2015. Dropping TPAB bestowed a crown upon Kendrick’s head; he was, suddenly, a torchbearer for progressive, conscious hip-hop. JID, no-doubt a progeny of Kendrick’s creative apex, dropped a lights-out TPAB sibling a few months after Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers crashed the year’s party. Kendrick was mentioned in the same conversations as the Mos Defs, Lupe Fiascos and Commons of the world; he was supposed to be epochal voice of Blackness in rap, thanks to his third studio album, released four months before he turned 28 years old, putting a cap on the Obama years with a resounding, 16-psalm reckoning with radical Black politics and a venomous, still-present Americana.

DAMN. told a different story—a timeless story of trauma and survival with its lens pointed inward. As a follow-up to one of the greatest rap albums of all time, it was a letdown. As an album standing alone in the pantheon of the man who held the pen, it was another triumph worth the two-year wait. Like the institutional failures under the knife on TPAB, DAMN. put the ramifications of a lifelong interpersonal crisis on display. Expectations, addictions, violence, legacy—it’s all there, wrapped into one stirring, vilified, boastful medley of woe. But the importance of To Pimp a Butterfly continued to follow Kendrick Lamar into a new decade. There was an absence, though. Ever the architect of a multi-generational language, the 2020s started to erode away and we escaped a few lockdowns without a K.Dot record to help make sense of the very same pandemic most of us lived through. I think, in hindsight, the truth is clearer than ever: You can’t make music about dying forever. Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers, flaws and all (namely the one step forward, two steps backward “Auntie Diaries”), was an earnest, eye-opening text from a man who, really, has always just been a son of Compton, California and not much else—a man who’d survived but hadn’t once turned his back on the very wreckage that hurled him ashore.

I find myself returning to one song from Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers often: “Mother I Sober.” I think, in the lexicon of Kendrick Lamar’s world, it’s the most definitive example of who he is as a writer. It’s a no-punches pulled, contradictory and egotistical transformation that gnawed at the truth of the Kendrick we know by showing us the Kendrick we rarely saw. Generational grief, with the hope that healing exists on the other side of hurt, spilled into the culture and industry Kendrick works in (“I know the secrets, every other rapper sexually abused / I see ‘em daily burin’ they pain in chains and tattoos”). Family habits and nature-versus-nurture come aplenty: Kendrick’s mother was abused and his uncle sought retribution; addiction is a centerpiece for community harm; newfound sobriety comes not as an excuse, but as a measure of grace; guilt and shame are the antithesis to growth; karma is prayed upon while bodies remain sacred.

I bring this up because the Kendrick we meet on GNX was heard two years ago on “Mother I Sober.” The viciousness he delivered the “A conversation not bein’ addressed in Black families / The devastation, hauntin’ generations and humanity / They raped our mothers, then they raped our sisters / Then they made us watch, then they made us rape each other” verse with comes as a lived-in, tangled web of misogyny, pride, chaos and judgement. It was that ferocity of grievous intent that allowed him to pick Drake apart piece by piece earlier this year; it’s a mourning that opens the door up for recovery—a recovery Kendrick’s ancestors weren’t afforded. He dreams of having superpowers strong enough to prevent his own children from inheriting all that impedes him from a kind of morality that exists with compromise but not casualty. Two years ago, it felt like there was closure in that, in saying the words long after everyone quit listening.

Whether or not the ending of “Mother I Sober” is full of ego or autonomy is up to whomever is listening to it, as the song concludes with Kendrick’s longtime fiancée Whitney declaring that he broke a generational curse and his children thanking him for re-calibrating their inheritance. Who is responsible for answering every man’s equation? I don’t know, but I think rapping about all of the faults that have collapsed into you—the very same faults that you have no doubt perpetuated, because you are as imperfect as the rest of us—and, in turn, devising your own absolution is an act of reclamation. Who will be the architect of our own grace but us?

GNX’s release was a surprise to many, but the paper trail was there. At the beginning of the “Not Like Us” music video, he teased what would become “squabble up” and, during the MTV Video Music Awards in September, he dropped a then-untitled track on his Instagram page that started with a massive declaration: “I think it’s time to watch the party die.” A summer of clubs across the world shouting “certified lover boy, certified pedophile” to the high-heavens later and Kendrick was ready to start rap music’s rebuild—wanting to trade “all of y’all” for the late, “sunken place”-bound, haunted Nipsey Hustle. Calling GNX “aggressive” feels like a disservice to the clarity Kendrick has earned, so let’s not mistake the genius of the“kill ‘em all before I let ‘em kill my joy” line for violence. Any interstitial meanness pales in the company of the record’s greater idea: Kendrick Lamar wants to make rap a better place or, at the very least, burn it to the ground and start from scratch—all while he counts the thorns of his own crown from the very top of the detritus. “Tell me why you think you deserve the greatest of all time, motherfucker / I deserve it all,” he raps at the end of “man at the garden,” questioning and declaring his oneness in a single breath.

Jack Antonoff, who produced “6:16 in LA,” nabs a production credit on 11 of these 12 songs—a move that has prompted many talking heads to question how he could graduate from making milquetoast arrangements on an album like Midnights to cushioning all of Kendrick’s daggers with soulful sounds that emphasize the rapper’s LA roots so aptly. It’s why a song like “luther,”which samples Luther Vandross and Cheryl Lynn’s “If This World Were Mine” and features contributions from Kamasi Washington, will go down as one of his sweetest efforts yet. This publication has not been kind to Antonoff’s musicianship and production, and I certainly have been one of his most vocal detractors. But his work on GNX with Sounwave (who previously worked on Mr. Morale) boasts a special awareness, as the two pair Kendrick’s continuity with beats that sound anything but dated (a stark contrast to Midnights (and even parts of The Tortured Poets Department), an album with synth-pop elements that arrived out-of-style on release day)—notably, the sample of Debbie Deb’s “When I Hear Music” on the “squabble up” arrangement sounds vibrant and nuanced.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-