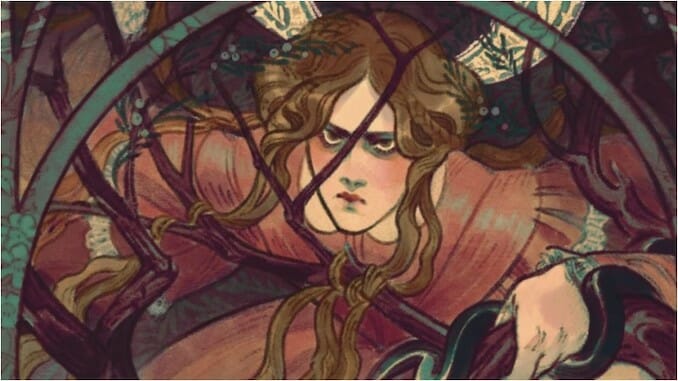

Juniper and Thorn Is a Lush Fairytale with a Dark Heart

Author Ava Reid’s debut novel The Wolf and the Woodsman was one of 2021’s most unexpected delights, a complicated, evocative tale of faith and folklore that explored how both can be and frequently are weaponized culturally against those with the least power within a society. And in many ways, her second novel manages to surpass her first.

Juniper and Thorn is technically a fairytale, but not in the way we’ve been trained to expect. A magical Gothic horror story of monstrous fathers, untrustworthy sisters, and lost innocence, this is a tale where a heroine has to save herself from a viciously patriarchal system, but she won’t be able to keep the blood off her hands while she does so. (Either figuratively or literally speaking.)

In the vaguest sense,Juniper and Thorn is a retelling of the Grimms Brothers’ story “The Juniper Tree,” in which an evil stepmother tricks her husband into eating his own son for dinner. Narratively speaking, the two tales have little in common beyond the name of a central character, the presence of the titular tree, and a painfully forthright depiction of cannibalism, but this more modern update certainly revels in a similar level of violence and gore.

Reid’s version is set in the town of Oblya, a vaguely Eastern European-esque city in the grips of profound cultural change, as magic and folklore are being pushed aside in favor of science and technology. Here, at this crossroads of superstition and cultural advancement, sits Zmiy Vaschenko—the last true wizard in the kingdom and a man who hates capitalism, the ballet, and all signs of modern progress—who keeps his three witch daughters locked away in their crumbling cottage. Eldest child Undine is a seer, who can divine the future in her scrying pool; middle daughter Roserot is a herbalist capable of making powerful potions; and the youngest, Marlinchen, is a flesh diviner, able to use touch to read people through their skin.

The girls have little freedom under the watchful eye of their father, who suffers from a debilitating curse of his own and who refuses to let them leave or see anyone who isn’t a paying client. (And his idea of the services these clients are allowed to pay for runs a long and often disturbing gamut.) When the girls sneak out to the ballet one night, Marlinchen accidentally meets Sevastyan, the theater company’s principal dancer, on whom she develops an instant and obvious crush.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-