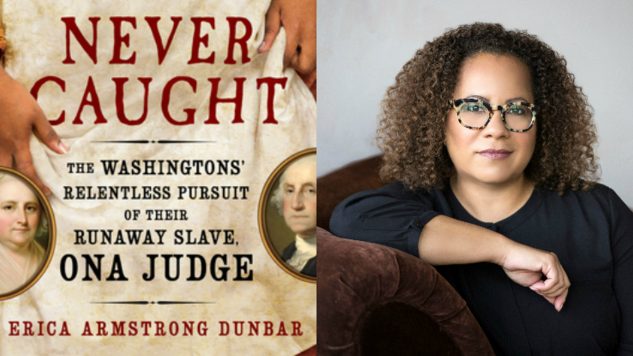

Erica Armstrong Dunbar Talks Never Caught, the True Story of George Washington’s Runaway Slave

Author photo by Whitney Thomas

On May 21, 1796, an enslaved 22-year-old woman named Ona Judge slipped out of her owners’ home in Philadelphia and into an illicit freedom. Runaways had become so common for America’s slave-owning gentry that three years before Judge’s escape, they pressured one of their own—the nation’s first president—into signing the Fugitive Slave Act. The law established guidelines by which slave owners could pursue their slaves into northern states that were moving away from slavery and into a wage labor system. Whether or not she knew the law’s specifics, Judge understood the manifold challenges she was facing by leaving Philadelphia behind. After all, the couple who claimed her as their property was the most powerful duo in the young nation. Their names were George and Martha Washington.

Historian Erica Armstrong Dunbar has written a book that, in detailing Ona Judge’s extraordinary life, illuminates how George Washington* remained committed to the institution of slavery—so much so that he spent years trying to capture Judge and return her to Mount Vernon, where she had been born and raised. Judge was Martha Washington’s* legal property, and Martha’s wealth—heavily concentrated in the humans she claimed—far exceeded her husband’s.

Dunbar first came across Judge’s name while conducting archival research for her debut book, A Fragile Freedom: African American Women and Emancipation in the Antebellum City, an academic study of free black women in the 19th century. While scanning the pages of a Philadelphia periodical, Dunbar discovered an advertisement announcing that a “light Mulatto girl, much freckled, with very black eyes, and bushy black hair” had run away from the president’s home.

“Her name and the situation behind the advertisement were more than intriguing. It seemed a little odd to me,” Dunbar said in a telephone interview with Paste. “Who is this person and what happened to them—and why don’t I know this?”

Dunbar considered including Judge’s story in A Fragile Freedom, but she decided against it in favor of later creating a project devoted to Judge’s life. That project became Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Dunbar’s sophomore book released in February.

Ona Maria Judge was born in 1773 to Betty, one of Martha’s most trusted slaves, and Andrew Judge, an English-born white man who had served the Washingtons as an indentured servant. In 1789, when George was unanimously chosen by the U.S. Senate to become President of the United States, Judge was among a small group of slaves who accompanied the “first family” to New York, the nation’s capital at the time. But it was when the capital and the president were relocated to Philadelphia that Judge grew aware of the differences in the public’s acceptance of slavery between Northern and Southern states. Pennsylvania law, Dunbar writes in Never Caught, “required the emancipation of all adult slaves who were brought into the commonwealth for more than a period of six months.”

“I don’t want us to paint the image of the benevolent North who were against slavery because they understood the moral bankruptcy behind it,” Dunbar said. “There were of course people who did feel that way, but I would also argue it was the economy. A wage labor system that does not work with a system of slavery alongside it would perhaps force some to be against the institution of slavery.”

Whatever the Pennsylvania law’s roots, it provided the Washingtons with a distinct problem. Their wealth as landed gentry was directly tied to the people they claimed as slaves, and emancipation would cause them financial ruin. After consulting with the nation’s first Attorney General—himself a slave owner who had lost slaves to the Pennsylvania law—the Washingtons turned their legal problem into a logistical one, devising a system to cycle their slaves back and forth to Mount Vernon before their six months were up. Dunbar highlights George’s correspondence with his secretary to show how anxious the president was to preserve his—and his wife’s—wealth as Virginian farmers.

“I am not a [George] Washington biographer,” Dunbar said. “But he happens to intersect with this woman I’ve chosen to focus on, and I think it’s great. It shows us just how complicated slavery was not just for regular folks, for enslaved people themselves and for fugitives and free blacks, but also for slave owners, who for various reasons by the 1790s were thinking differently about slave ownership.”

While George may have held misgivings about slavery—culminating in his decision to emancipate his slaves after his death—Judge’s escape after five years spent cycling between Mount Vernon and Philadelphia presented him with a problem requiring a discreet solution. At the time, he was distracted by the 1796 election and the coming succession of John Adams to the presidency.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-