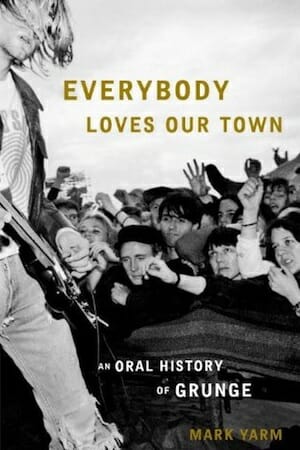

Everybody Loves Our Town: An Oral History of Grunge by Mark Yarm

When Seattle Ruled the World

Even if the term grunge makes you cringe as much as it does me and most of the musicians in this book, and even if you haven’t listened to Nirvana’s Bleach or Soundgarden’s Screaming Life in years, you’ll love Mark Yarm’s 550-plus pages of good rock-’n’-roll storytelling.

Want to know how someone chainsawed a hole in the wall of a punk club during a show to satisfy the fire department’s complaint that there weren’t enough fire exits? How U-Men played Bumbershoot and threw a lit broom into a stage-side pond filled with lighter fluid, shooting a fireball 20 feet in the air? Forget the marketing terminology and media oversaturation we’ve grown to associate with ’90s Seattle. You only need to appreciate tales of talent, ambition and youthful indiscretion to enjoy this wonderful book.

Published to coincide with the 20th anniversary of Nirvana’s Nevermind and Pearl Jam’s debut Ten—two albums that forever changed rock music (and Seattle)—this definitive book on Seattle’s late-’80s/early-’90s musical landscape contains more than 250 interviews Yarm conducted. The author took the book’s title from a line in Mudhoney’s song “Overblown,” featured on the soundtrack to Cameron Crowe’s pre-global-feeding-frenzy movie Singles. (Don’t let that fool you. It’s a killer song.)

Yarm gives us Sub Pop chapters, Mudhoney chapters, a Malfunktion chapter too, though the book proceeds chronologically from the pre-grunge band U-Men and covers everyone from Soundgarden to The Melvins to The Gits. For fans of these innovative bands, this book is the bar conversation that you’ve always dreamed of being a part of.

Details?

Soundgarden’s final bassist, Ben Shepard, toured with Nirvana as their second guitarist but never played, only sold merch and loaded equipment, because the band wasn’t playing the future Nevermind material he’d learned.

Faced with two interesting seven-inches, Courtney Love bought Cat Butt’s single over Nirvana’s “Love Buzz” because she didn’t like the Harley-Davidson shirt Cobain wore on the record sleeve.

L7’s singer Donita Sparks brought Cat Butt guitarist James Burdyshaw to a drugstore to buy him Depends because he had such bad stomach flu on their Swapping Fluids Across America Tour.

Dwarves bassist Salt Peter found a can of spray paint in the Sub Pop office and wrote on the floor YOU OWE DWARVES $.

Unfortunately, you have to hear the name Candlebox a few times in the process, but that’s worth the price of admission.

Yarm’s book works so well because it’s an oral history, not a narrative one. It isn’t analytical. It doesn’t offer insight into its subject by editorializing or trying to show its subject in a larger historical context. It’s not cultural criticism, like other stellar books such as Simon Reynold’s Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past. Instead, it’s a collection of trimmed and sequenced quotations as raw as sashimi—just spoken words, a naked man on the street, telling it like it was.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-