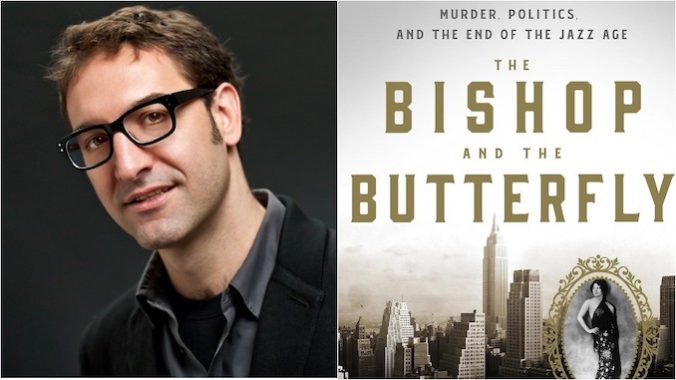

Devils of New York: The Bishop and The Butterfly Author Michael Wolraich on the Everyday Monsters of History

Photo credit: Deutsch Photography

We’re all familiar with the world’s most notorious villains, the brutal dictators and vicious psychopaths who haunt the history books. But for every Adolph Hitler and Charles Manson, there are thousands of lesser villains, neglected or forgotten, who inflicted misery within their own small corners of the world.

Martin Scorsese’s latest cinematic opus, Killers of the Flower Moon, shines a spotlight on one of those “little” devils, a man without conscience who murdered Osage Indians for profit using poison, bullets, and bombs. “This is a story that’s as close to good and evil that I’ve ever reported,” observed David Grann, author of the bestselling history book by the same name on which the film was based.

Those who have watched the film or read the book know who the culprit was, and I won’t spoil it for the rest. Yet the villain portrayed in the movie, which covers the first two-thirds of the book, wasn’t the only little devil who preyed on the Osage in the 1920s. The last third of Grann’s book exposes a broad conspiracy by many white settlers to murder Osage people for their oil wealth.

“We like to think of crime stories as this one bad thing or person,” Grann explained. “That’s kind of the standard narrative of detective fiction and true crime stories…But this is a story where you begin to realize that that same evil lurked in the heart of so many ordinary people, and that so many people were either committing murders within their own family or they were willing executioners who went along, or they were morticians who covered up the crimes, or they were press or reporters who didn’t cover them, or they were politicians who were profiting from the crimes and ignoring them, or they were lawmen who were getting kickbacks.”

My forthcoming book, The Bishop and the Butterfly: Murder, Politics, and the End of the Jazz Age, is also full of little devils. Like Grann’s book, this true story unfolds during Prohibition, but it’s set in New York City, about as far as you can get from an Oklahoma prairie. There is only one murder victim, a beautiful woman named Vivian Gordon whose body was discovered in a Bronx park in 1931 with a dirty clothesline wrapped around her neck. The tabloids dubbed her the “Broadway Butterfly.”

Many of the devils from my book were murder suspects—the boyfriend who manipulated her, the vice cop who framed her, the ex-husband who took her child, the gangsters who owed her money, the madam who exploited her, the businessmen whom she blackmailed. “Vivian was due to get the business,” one suspect opined, “I know a dozen reasons why she might have been rubbed out.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-