Paul Tremblay Talks Horror Movie, Cursed Films, and What Makes Cinema Scary

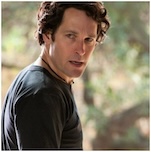

Through books like A Head Full of Ghosts, The Pallbearers Club, and The Cabin at the End of the World, Paul Tremblay has become one of the most acclaimed horror novelists working right now, weaving strange, very specific stories that only he could tell. His latest, Horror Movie, is another singular achievement from one of our finest weavers of scary stories, with lots of metafictional twists.

The horror movie of the title is an independent film shot in the ’90s, a film that was never released save for three scenes that appeared on YouTube years after production ended. Those three clips were enough to spark a rabid cult fandom for the unreleased released project, also titled Horror Movie, and with that kind of fandom comes the possibility of a remake.

At the center of that possibility is the actor who played “The Thin Kid” in the original film, the last surviving member of the cast, who’s forced to reexamine everything he knows about his friends, what went wrong, and why his character has never really left him.

In anticipation of the book’s release, we sat down with Tremblay for a discussion about writing a movie within a book, his favorite horror films, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, and much more.

Paste Magazine: In the acknowledgments at the end, you mention that this book was at the bottom of a rabbit hole that started with a conversation between Walter Chaw and John Darnielle about The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. How did that lead to this?

Paul Tremblay: Stephen Graham Jones recommended Walter’s [film series via the Denver Public Library], he was doing Saturday matinees, sort of like old-school Saturday matinees. He and the library would show a movie, but then he would have this amazing discussion. I can’t remember if Stephen sent me that episode, in particular, or if it was just the first one I watched, but I watched Walter and John Darnielle talking about Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

So I watched these two incredibly smart and talented people talking about the movie. It was just so infectious. And the first thing I did was I went and rewatched the movie, and during the YouTube talk, Walter held up a copy of Gunnar Hansen’s [memoir] Chainsaw Confidential. And when I listened to that, that really sort of crystallized this idea that I wanted to work with, because at the time I was in between novels. I had an idea for something, but I wasn’t loving it, so it was a sign to me that I needed something else. But I listened to the audio version, because it’s hard to find any print copies of Chainsaw Confidential anymore.

I think The Thin Kid is certainly very modeled off him in some ways, because, well, he’s narrating the audiobook. I mean, it’s really beautifully written. It’s very winky, and he feels dangerous in some ways. I think he purposefully sort of blurs the line between what he’s thinking and maybe what Leatherface would be thinking.

So that plu amount of chances that the crew and the director and the actors took, both financially and physically [making Texas Chain Saw]. Something really bad could have really happened. So all of that together was like, “Oh, OK, what if something really bad had happened?” It was really sort of the very start of it.

Paste: In terms of story, did it start with the movie within the book, or with the Thin Kid’s larger story?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-