The 30 Best Movies from Books on Netflix

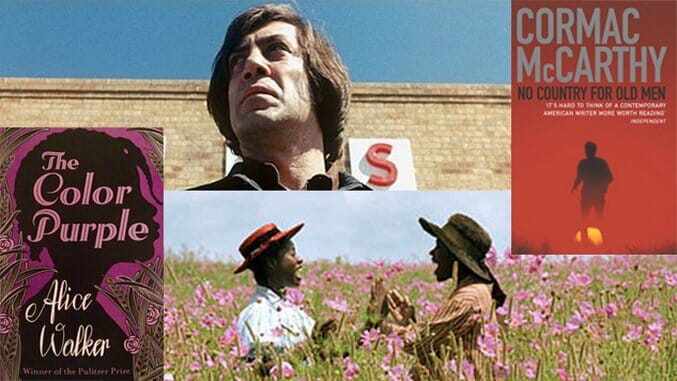

Looking for a good book adaptation on Netflix? We’ve got you covered with 30 great movies based on books you can read before you stream them on Netflix Instant.

The first attempts to adapt a novel into a screenplay weren’t the most successful. Austrian-American director Erich von Stroheim tackled Frank Norris’ novel Greed in 1924, and the first cut was nine-and-a-half hours long. Since then, filmmakers have learned to abridge the story to fit a more typical moviegoing experience.

The following 30 movies, all available to stream on Netflix in the U.S., were adapted from books, whether novels or works of non-fiction. Several were nominated or won Oscars for Best Adapted Screenplay. But all are successful attempts to take a beloved book and turn it into something more visual.

Here are the 30 best movies from books on Netflix:

30. The Bridge on the River Kwai

30. The Bridge on the River Kwai

Year: 1957

Director: David Lean

Author: Pierre Boulle (Le Pont de la Rivière Kwai, 1952)

Before he was beach-bumming on Tatooine, Alec Guiness was known by many as Lieutenant Colonel Nicholson in David Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai. The film, based on the French novel Le Pont de la Rivière Kwai by Pierre Boulle, follows a group of Allied comandos in the Burmese jungle as they attempt to destroy a bridge built by British POWs. Many times, explosions are exactly what they seem: dazzling and destructive. But in Kwai, the bridge’s destruction is a symbol for the film’s thematic message on war as a whole, as Major Clipton aptly describes in the closing scene as “madness.”—Darren Orf

29. Forrest Gump

29. Forrest Gump

Year: 1994

Director: Robert Zemeckis

Author: Winston Groom (1986)

Few films infiltrate the collective American psyche quite the way Forrest Gump managed. You’ve undoubtedly heard someone make reference to this 1994 classic—whether it was a classmate sarcastically yelling “Run, Forrest, run!” as you hustled to catch the bus, or someone busting out their best drawl to deliver, “Momma always said life is like a box of chocolates.” The entire film is full of dialogue that’s both moving and funny (my personal favorites include “But Lt. Dan, you ain’t got no legs” and “I’m sorry I had a fight at your Black Panther party”). Forrest may be a simple man, but his story—written by Winston Groom in his 1986 novel of the same name—is our nation’s story, and we all are run through the emotional gauntlet as we watch him hang with Elvis and John Lennon, fight in Vietnam and encounter many a civic protest—all while in pursuit of his true love, Jenny. Tom Hanks delivers an Oscar-winning performance, and Gary Sinise is heartbreaking as Lt. Dan.—Bonnie Stiernberg

28. The English Patient

28. The English Patient

Year: 1996

Director: Anthony Minghella

Author: Michael Ondaatje (1992)

It wasn’t just Elaine Benes who thought that The English Patient was overrated and boring: Even at the time of its Oscar win, this period romantic epic was being criticized in some quarters for its self-consciously old-school sweep. To which its fans say, “Yeah, so?” A stellar “They don’t make ’em like this anymore” movie, filmmaker Anthony Minghella’s adaptation of Michael Ondaatje’s novel starred Ralph Fiennes and Kristin Scott Thomas as the most poignantly star-crossed big-screen lovers since Ilsa walked backed into Rick’s life. Beautifully shot, sensitively acted, romantically overpowering, The English Patient is way, way better than Sack Lunch.—Tim Grierson

27. Cold in July

27. Cold in July

Year: 2014

Director: Jim Mickle

Author: Joe R. Lansdale (1989)

Richard Dane seems like a decent-enough man. Living in East Texas in 1989, he has a wife and child, and when he hears a noise coming from the living room late one night, he goes out cautiously, holding his dead father’s gun tentatively. He didn’t mean to kill anyone. And he certainly didn’t intend to have just about everything in his world change in the moment when he accidentally pulled the trigger. Michael C. Hall plays Richard, not overdoing the character’s regular-hick modesty. Adapted from Joe R. Lansdale’s novel, Cold in July has a steely, slightly off-kilter vibe. Less extreme than the regional portraits preferred by the Coen brothers, the movie soaks up the period details, particularly in Jeff Grace’s wry nod to the synthesizer-driven scores of the 1980s. As in his past films, Mickle demonstrates an impressive degree of tonal control: Cold in July clearly pays homage to a certain style of bygone genre filmmaking, but not at the expense of the characters or the stakes. (Still, not for nothing is a crucial scene set at a drive-in theater.) Consequently, the film has both a giddy, escapist feel and a grim suspense, its self-conscious artificiality melding perfectly with its barebones emotional authenticity.—Tim Grierson

26. Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

26. Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

Year: 2011

Director: Tomas Alfredson

Author: John le Carré (1974)

Steeped in the monochrome color palette and noir soundtrack of 1970s espionage cinema, Tomas Alfredson’s adaptation of John le Carré’s classic bestselling spy novel offers smart, nostalgic entertainment for a discerning adult audience. Set in 1973 at the height of the Cold War, the film turns on the suspicion that a double agent has infiltrated Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), a.k.a. MI6. Shortly after a botched operation to ferret out the mole ends his career, Control (John Hurt) dies, leaving his investigation in the hands of retired operative George Smiley (Gary Oldman). With grayed blond hair and owlish glasses, Oldman disappears into his role, not only physically but behaviorally. Smiley is a still man, watching and waiting, while his mind whirs, processing and analyzing years’ worth of data, information and memories.—Annlee Ellingson

25. Philomena

25. Philomena

Year: 2004

Director: Stephen Frears

Author: Martin Sixsmith (The Lost Child of Philomena, 2009)

Philomena, follows a woman’s search for her son, who was “sold off” by the Irish Catholic church 50 years earlier. Starring Judi Dench and Steve Coogan, the heartbreaking twists and turns of Philomena’s journey are even more jaw-dropping as we learn the story is based on the 2009 nonfiction book The Lost Child of Philomena Lee, by BBC correspondent Martin Sixsmith. In 1950s Ireland young Philomena (Sophie Kennedy Clarke) is disowned by her family after a tryst results in pregnancy. Sent to Roscrea convent, she works in the laundries to pay for her room and board—and her sins. She and the other young mothers are allowed to see their children for an hour a day. Philomena and her son Anthony adhere to this limited schedule for nearly three years until Anthony is adopted, against her wishes, on Christmas 1955. Nearly five decades later, the elderly Philomena (Dench) reveals the secret she’s been keeping all these years to her daughter. They reach out to Sixsmith (Coogan), a recently fired British government flack and former BBC journalist, to help Philomena search for her lost son. Although talking about “chemistry” is usually reserved for romantic onscreen relationships, it applies here in spades. Dench and Coogan create a believable rapport for their disparate characters. They play with the yin and yang expertly, and we watch as the characters both grow from their experience together in subtle, yet substantial, ways. The bittersweet mystery could have easily strayed into maudlin, tabloid territory, if it solely targeted evil nuns or a Catholic Church coverup. But instead, Philomena adds much-needed moments of humor s it follows the journey for the truth, raising questions about faith, infallibility and family. The steady direction by Frears, coupled with the snappy and substantive dialogue, keeps the film grounded when even the truth becomes hard to believe.—Christine N. Ziemba

24. Blue is the Warmest Color

24. Blue is the Warmest Color

Year: 2013

Director: Abdellatif Kechiche

Author: Julie Maroh (2010)

Three-hour movies usually are the terrain of Westerns, period epics or sweeping, tragic romances. They don’t tend to be intimate character pieces, but Blue Is the Warmest Color (La Vie D’Adèle Chapitres 1 et 2) more than justifies its length. A beautiful, wise, erotic, devastating love story based on Julie Maroh’s graphic novel, this tale of a young lesbian couple’s beginning, middle and possible end utilizes its running time to give us a full sense of two individuals growing together and apart over the course of years. It hurts like real life, yet leaves you enraptured by its power.—Tim Grierson

23. Hard to Be a God

23. Hard to Be a God

Year: 2015

Director: Aleksei German

Author: Arkady and Boris Strugatsky (1964)

Aleksei German’s final film is a stark, wild journey through medieval sci-fi filth. Like the drunken bastard child of a dreamy Andrei Tarkovsky epic and a Terry Gilliam yarn, in Hard to Be a God we see hints of Tarkovsky’s pensive takes, as well as his predilection toward existential speculative fiction (he adapted his 1979 film Stalker from a novel by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, the same Russian brothers who wrote Hard to Be a God in 1964), coupled with a sort of sensory overload as German’s frames wander through countless intricate details that call to mind Gilliam, another director attracted to obsessive, timeless dystopia. Tarkovsky may have a penchant for surreal confusion, but he anchors his oneiric sensibilities in characters’ motivations, desires, and souls. Here, there’s no real motivation, no real desire, and no real soul, just a crawl through depravity. But if that’s all you’re after, then here you go: This shit is executed majestically. —Jeremy Mathews

22. The Big Short

22. The Big Short

Year: 2015

Director: Adam McKay

Author: Michael Lewis (The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine, 2010)

The Big Short, Adam McKay’s kaleidoscopic look into the months leading up to the 2007 financial meltdown, is an angry film. And rightfully so—the amount of callous thievery characters uncover here is enough to make any rational person’s blood boil. It’s also, unquestionably, a funny film, tempering its acerbic leanings by highlighting just how blatantly surreal the whole ordeal truly was. Based on Michael Lewis’ award-winning non-fiction account of how our economy crashed, McKay looks to counteract the inherently dry, impenetrable subject matter on display with boatloads of vibrant, cinematic style. The Big Short may not always succeed, but it stands as an essential film nonetheless.—Mark Rozeman

21. Breathe

21. Breathe

Year: 2014

Director: Mélanie Laurent

Author: Anne-Sophie Brasme (Respire – 2004)

Nothing’s more effective at shaking a teen out of their monotonous high school routine than the arrival of a new student. That’s the stuff actress/director Mélanie Laurent’s sophomore film, Breathe, is made of: mystery and allure, with generous dollops of adolescent rivalry, sexual awakening and verbal abuse spooned on top. Think of Breathe as a distant European cousin to the fraught teen movies of Larry Clark as well as Catherine Hardwicke’s Thirteen, stories of imperiled youth, loneliness and volatile sentiment.—Andy Crump

20. Phoenix

20. Phoenix

Year: 2014

Director: Christian Petzold

Author: Hubert Monteilhet (Les Retour des Cendres – 1961, loosely adapted)

Rarely in recent memory has the insoluble mystery of other people been so potent a driving force as it is in Phoenix. Here’s a drama that starts off with a seemingly simple conceit but eventually grows more and more troubling—and fascinating—into a critique of collective moral blindness and an up-close examination of marriage. The latest from German filmmaker Christian Petzold, Phoenix works best for all the answers it doesn’t provide, honoring the mysteries of everyday life rather than explaining them away.—Tim Grierson

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

19.

19.  18.

18.  17.

17.  16.

16.  15.

15.  14.

14.  13.

13.  12.

12.  11.

11.  10.

10.  9.

9.

7.

7.  6.

6.  5.

5.  4.

4.

2.

2.  1. No Country For Old Men

1. No Country For Old Men