The 50 Best Movies of 2024

The best movies of 2024 transported us, as they always do in the best of times, to far away worlds and escapist fantasies of the highest order. And to be frank, many audience members needed the reprieve: A year of utter chaos in U.S. society and politics culminated in grand disappointment for many, and an uncertain future for many hallowed institutions. The movies certainly weren’t immune, posting overall box office dips from 2023, reflecting the ever-expanding ripple effect of the actors and writers’ strikes from last year. Only now is the release calendar really starting to feel “back to normal,” or as normal as anything can ever really be in the post-COVID world.

Thank god, then, that there were still scores of standout movies to appreciate–dramas, romances, documentaries, farces and the best year for body horror in recent memory. Body snatcher movies insidiously made a play for sci-fi dominance, while the Marvel Cinematic Universe regathered its energy with its most quiet year in a decade. New names rose to the top of our cinematic ranking, while old masters like George Miller proved they still had at least one more epic left in them. It was a year of daunting architecture, of impulsive, star-crossed lovers on the run, of fucked-up cosmetics increasingly turning people into quivering piles of goop. And of course, it was a year of beavers–so very many beavers. If you still haven’t gotten around to watching Hundreds of Beavers, we can promise you that you’re not imagining nearly enough beavers. You’ll just have to trust us on this.

Here, then, are the 50 best movies of 2024:

![]()

50. The Promised Land

Director: Nikolaj Arcel

Mads Mikkelsen plays Ludvig Kahlen, a retired military officer living in 18th-century Denmark who’s hellbent on cultivating the Jutland heath, a stretch of land considered impossible to farm. If he can accomplish this seemingly undoable task, he’s been promised a noble title, a goal he chases with obsessive resolve. But beyond taming this infertile landscape, he also must contend with Frederik de Schinkel (Simon Bennebjerg), a sadistic magistrate willing to spill blood to ensure he retains control over the region. As Kahlen spends every penny of his meager pension to cultivate this space, a stand-off brews between these men, each determined to get his way. While The Promised Land largely takes place on a relatively tiny plot of dirt in the Danish boonies, its filmmaking lends this struggle an expansive, David-versus-Goliath slant. Cinematographer Rasmus Videbæk and director Nikolaj Arcel contrast the breadth of the Jutland countryside against the smallness of our protagonist’s enterprise as he cuts through vast shrubland and tills acidic soil in what initially feels like a futile and hubristic effort. But what makes The Promised Land truly compelling is how it naturally grows into something else, as Kahlen nurtures a seed of doubt about his ultimate aims. Mikkelsen deftly embodies these turns with subtle gestures that bring out internal struggles, and it’s deeply satisfying to watch as his icy demeanor at least marginally melts. The toughness of these surroundings makes it feel all the more precious when he finds his unexpected connections. But, thanks to Mikkelsen’s performance and Kahlen’s characterization, even at the heights of their happiness, there is a genuine uncertainty around how things will break, a relative rarity in a storytelling landscape where the protagonist’s final decision often comes across as perfunctory and obvious. It all comes together to make The Promised Land a stirring historical epic that balances its grandiose framing with something surprisingly grounded and genuine. A bountiful harvest indeed.–Elijah Gonzalez

49. Wicked

Director: Jon Chu

It’s more than fair to say that the Broadway show Wicked is pop-u-lar. With more than one-and-a-half billion greenbacks earned since its debut back in 1995, the Stephen Schwartz penned musical with a book by Winnie Holzman based on Gregory Maguire’s novel has proven that its verdigris is more than skin deep. Ever since its storming the stage there’s been talk about a film version, with the project wrapped in development for these many decades, with generation upon generation of fan continuing to embrace its story of perseverance and powerful transformation while wanting something … more.

Chu’s film defies already high expectations, takes the storyline to new heights, and brandishes its exceptional ensemble to craft one of the great musical movies of this or any age. This is the type of telling that this storyline deserved, employing the scope and sizzle of old Hollywood with a fresh new bent. Generations upon generations will look to this version of this telling for inspiration, and for those that know every note of the score ahead of time, to those new to these environs, they’ll be in for a treat. This film is as good as this project could ever hope to be, and it bodes well that Part Two will live up to everything that’s been set up here. When granted the chance to see them back-to-back, we just may, as the song goes, all be changed for the better. After this first act, it’s already safe to claim that Wicked is frickin’ Oz-some. —Jason Gorber

48. National Anthem

Director: Luke Gilford

Dylan (Charlie Plummer) is down on his luck. A 21-year-old construction worker working odd jobs in rural New Mexico, he struggles to bring home enough cash to support his family—let alone initiate the glorious and messy process of hacking into the barren, unexplored terrain of his own interests, hopes and dreams. Things take a change, however, when Pepe (Rene Rosado) pulls up to Dylan’s worksite, soliciting a handful of farm-hands for a mysterious job. Desperate for work, Dylan hops into the back of Pepe’s pickup truck, blissfully unaware that his one-note life is about to change for good.

The destination is The House of Splendor: A ranch run by Pepe and his partner Sky (Eve Lindley), a free-spirited, hypnotic barrel racer. Everyone who sets eyes on Sky is instantaneously transfixed. Dylan is no exception. Typically reserved and aloof, he begins to fantasize about her: Sitting bareback on a horse against the magnificent backdrop of rugged western mountains, bathed in luminous desert light. You can probably guess where this is going, right?

Don’t be so sure. The beauty of National Anthem is that it effortlessly challenges all expectations and preconceived notions. Helmed by photographer Luke Gilford in his feature directorial debut, National Anthem is an extension of his 2020 photo project of the same name, which showcases the International Gay Rodeo Association. Throughout the work, Gilford uses rich, tender, intimate portraits of queer cowboys to refute our pre-established perception of Americana culture and aesthetic. —Aurora Amidon

47. Thelma

Director: Josh Margolin

Every good action hero knows you’ve got to stick to your guns. Ethan Hunt is a marathon-running master of disguise. John Wick has never lost count of his remaining bullets. Jackie Chan’s various inspectors and agents view the world as their personal set of monkey bars. When writer/director Josh Margolin’s debut Thelma keeps its sights trained on its rogue granny on a mission (June Squibb), its hilarious geriatric reframe of action-movie tropes has a game champion. Like its absentminded hero, the film can sometimes get sidetracked right when things are getting good, wandering down schmaltzy or twee narrative paths. But when it lets Thelma (and Squibb) do her thing, the comedy is perfectly cute and a stellar showcase for what an actor’s late career can offer.

In fact, much of Thelma is about adjusting our ideas around aging. There’s novelty in the comedic turns from the 94-year-old Squibb and her 81-year-old co-star, Richard Roundtree (in his final film role). These actors get to tap a well that’s unique to their age and the genre without sticking them into the boxes that generally contain old performers. They’re not utterly dignified, wisdom-dispensing elders. They’re not tragic victims of time. And they’re certainly, blessedly not the dreaded “rapping grannies” who are more punchline than performer. As the pair abscond on their quest to retrieve Thelma’s stolen savings, solicited from her cookie jar and mattress by phone scammers, they’re clearly complex, pulling off warm humor, endless charm and impressive stunts. A 94-year-old doesn’t have to ride a motorcycle off a cliff to make you gasp. —Jacob Oller

46. Small Things Like These

Director: Tim Mielants

In his first credit as a producer, Cillian Murphy, alongside director Tim Mielants, offers a profound story inspired by very recent history. Based on the novel by Claire Keegan, Small Things Like These follows Bill Furlong (Cillian Murphy), a coal merchant who stumbles upon the abuse occurring at a local Magdalene laundry, an institution that supposedly offered rehabilitation to “fallen women” (largely sex workers and unwed mothers), but in reality operated more like a workhouse.

The film opens with Bill watching as a young woman is dragged into the local convent, her mother ignoring her apologies and pleas to take her home. Though visibly disturbed, Bill walks away and returns home to his daughters, clearly haunted by what he has seen. This opening sequence establishes the film’s focus on the role that willful ignorance played in the continuation of abuse at these institutions. Young women, abandoned by their family and exiled by society for being “sexually promiscuous,” were forced to work at these laundries under excruciating conditions for little to no pay, and often endured abuse at the hands of the nuns who ran the laundries. In the film’s setting of New Ross, an intricate web of power is woven to ensure that the church is able to get away with these crimes by having a hand in almost every aspect of town life. In Small Things Like These, melancholy seeps through every frame. Unlike other dramas of a similar vein, Mielants’ film doesn’t have a neat ending where justice is served in the name of all the young women who were harmed. Instead, the film lingers at a time when the abuses were still ongoing, forcing us to reckon with the reality of such a recent horror. —Nadira Begum

45. Evil Does Not Exist

Director: Ryusuke Hamaguchi

Evil Does Not Exist opens with the camera languorously tracking through treetops, seen from the ground, until interrupting itself abruptly with a music-stopping shot of Hana (Ryo Nishikawa), a grade-school-aged girl with her neck craned up – suggesting we were previously sharing her point of view. The implied closeness of that opening shot is the nearest the camera gets to its characters for a while; it’s 10, maybe 15 minutes before anyone in the movie is seen in anything resembling a close-up. We meet Takumi (Hitoshi Omika), Hana’s father, and figure out some details of their life, explaining the remoteness of the cinematography: They live in a woodsy Japanese village, broadly isolated but not alone, enjoying the quiet. We watch as Takumi performs outdoorsy tasks — chopping wood, hauling fresh well water — until we realize that, put together with minding Hana, they form his job, of sorts. Takumi and Hana aren’t that far from society; Takumi delivers the well water to a local udon restaurant, not exactly a strictly survivalist outpost. But there’s something pristine and untouched about their environment, making the interest of a company called Playmode both natural and horribly unnatural all at once. For a little while, it seems like Hamaguchi has made his own quiet, non-cutesy version of the story where the company man is tasked with steamrolling a small town, only to find himself charmed by its inhabitants and way of life. Evil Does Not Exist doesn’t exactly swerve away from that narrative; instead, it shifts again, slowly but surely, this time into more unsettling (and unsettled) territory. Hamaguchi’s previous film, his U.S. breakthrough and recipient of a Best Picture Oscar nomination, was the deliberate, sometimes mesmerizing Drive My Car. Evil Does Not Exist is only a little over half that movie’s length, and though it allows its characters a certain measure of soul-bearing conversation, it plays certain offscreen developments even closer to the vest. Hamaguchi’s film – and the performance style of Omika, a Hamaguchi crew member moving into acting here – is too controlled to produce an anguished tragedy out of this material, but it’s too unsparing to offer an easy exit. Even the most formidable steamrollers can’t always clear a path out of the wilderness.–Jesse Hassenger

44. By the Stream

Director: Hong Sang-soo

Although many Hong Sang-soo signatures are present in his newest film—scenes written the morning of; long, inebriated talks over delicious meals; lovely performances from his regular players—By the Stream marks a subtle but striking shift in his preoccupations and artistry.

Jeon-im (Kim Min-hee, a rare, true movie star), an arts professor at a women’s college in Seoul, spends her free moments sketching the patterns of a local stream, to be woven on her loom later. When she’s not creating her own textile art, she’s teaching her small group of performance art students. The harmony of the group is thrown off course when the male student director from another university dates three of her female students at the same time, with only one week left until the big theater performance. To solve this quickly, Jeon-im asks her estranged uncle Chu Si-eon (Kwon Hae-hyo), a widely celebrated stage actor/director, to write a new script and finish directing the project. To her surprise, he gladly obliges. Unbeknownst to Jeon-im, her bone-deep sense of solitude runs in the family, so he’s happy for the artistic exercise and sense of community. Jeon-im introduces him to her boss, Professor Jeong (Cho Yun-hee), who was already quite fond of him from afar.

Together, the three form a brief artistic family in their collective responsibility to compassionately guide the four female students left in the class into a more mature artistic practice and way of thinking. For my money, I have never seen a Hong film in which the main focus throughout the film is pointed at the essential human capacity to protect and comfort each other, across age groups. —Katarina Docalovich

43. Io Capitano

Director: Matteo Garrone

Seydou (Seydou Sarr) wakes up in his bed in Dakar, Senegal to the sound of his sisters singing and trying on wigs. The 15-year-old tells his mom he’s leaving to play football with his cousin, Moussa (Moustapha Fall), but the pair secretly go work on a construction site to pay for a voyage to Italy. Seydou is a good-natured, charming teenager with a secret: He dreams of making music in Europe. As Moussa puts it, he’ll one day make “white people line up for autographs.” Once they leave Senegal, the two bright-eyed teenagers who write music and sing in the streets are met with harrowing conditions in the desert, in corrupt prisons and finally behind the wheel of a ship that completes their journey to Italian shores. Italian director Matteo Garrone, known for helming violent, nihilistic works such as Gomorrah and Dogman, takes a more optimistic pivot with Io Capitano.

The real three-year voyage of Mamadou Kouassi inspired the film; Kouassi advised Garrone on incorporating many aspects of his own journey into the movie, such as encountering torture in a corrupt Libyan Prison and working as a slave laborer on a villa in exchange for his release.

Garrone flips the script and tells a migration story often not captured in popular media. Seydou and Moussa are not fleeing from violence or war, but are leaving the country they love to fulfill their desire for adventure and to experience the globalized European culture they absorb online. Io Capitano shows a lot of reverence for its subjects’ home country, even incorporating Senegalese spiritual customs into many scenes, such as a dream in which a messenger spirit visits Seydou in prison. In highlighting a different migrant story than typically showcased in popular media, the director points out the ramifications of racist immigration laws rather than painting its migrant characters as individuals who need saving. —Sage Dunlap

42. Ghostlight

Director: Kelly O’Sullivan, Alex Thompson

Ghostlight opens with darkness smothering the rustle and whispers of an audience making its way to their seats before the show starts. Then: The rattling hiss of the stage curtain opening. We expect to see actors, a set, props. Instead, we just see a suburban backyard, the property of Dan (Keith Kupferer), who’s awake much too early for his or his wife’s liking, but helpless to do anything about his REM cycles apart from stare forlornly outside. Life, the film tells us up front, is a show we all perform in. But in the rest of the telling, Ghostlight argues that acting specifically, and the arts broadly, are necessary tools for understanding it.

If this sounds precious, then a visit to Alex Thompson’s last movie, Saint Frances, may be in order. That film, like Ghostlight, takes seriously its central subject matter while at the same time surrounding it with the kind of shaggy naturalist humor that crops up in our daily routines and public interactions – small-talk humor with strangers, time-killing humor with coworkers, deflective humor with our families. Ghostlight is a comedy in a loose sense, a tragedy in another, and a redemption song in yet one more. More succinctly, it’s a Thompson film, meaning it gently, tenderly unpacks and embodies every single feeling its characters might have about their situation at hand. —Andy Crump

41. The People’s Joker

Director: Vera Drew

A feat of parody so outrageous that its legend (and strongly worded letter from corporate) precedes it, The People’s Joker is an endlessly amusing, deeply personal, wildly inventive collision of genres all bent to the will of filmmaker Vera Drew. Her queer coming-of-age is filtered through the language and imagery of Batman media, her transition and alt-comedy leanings all given hilarious reflections in the Rogues’ Gallery of Gotham. But it’s through the combination of DIY greenscreen work and effervescent, scrappy animation captured in populist media like Minecraft and VR Chat that the film’s indie production wins you over. The resulting collage is like visiting your childhood bedroom, and relating the sticker-covered walls to your adult life. Also, all the stickers are voiced by people like Maria Bamford, Scott Aukerman, Tim Heidecker and Bob Odenkirk. Drew herself is a charismatic performer, as is Kane Distler, who plays her romantic foil (who is also a Joker), but it’s Phil Braun’s ridiculous Batman that always steals the show. The riotous, anarchic result is everything the corporate use of the Joker isn’t, and everything it could be. The People’s Joker is a deftly assembled reckoning of how we use art — ranging from the cribbed comic aesthetic to the film’s Lorne Michaels-skewering comedy scene — to craft ourselves.–Jacob Oller

40. Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell

Director: Phạm Thiên Ân

Having a kid irrevocably changes a person’s life, and those changes are doubled when the kid arrives orphaned by tragedy. Two lives in flux, and the new parent is responsible for shepherding a little one through formative grief, on top of traditional parenting duties. But Thiện (Lê Phong Vũ), the laconic protagonist of Phạm Thiên n’s first feature, Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell, handles this abrupt charge with laid-back ease, as if his every experience has prepared him for the circumstance of his sister-in-law’s death and subsequent custodianship of his nephew, Đạo (Nguyễn Thịnh). Most people would be rattled by these events. Thiện rises to the occasion with preternatural nonchalance. His comfort with this solemn trust is not by any means the movie’s most fantastical quality. n follows in the footsteps of the greats of slow cinema, notably Tsai Ming-liang, Edward Yang and Apichatpong Weerasethakul, both in terms of taking his sweet time allowing Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell’s story to breathe, and in terms of judiciously applying surrealist brushstrokes to an aesthetic that verges on neo-realist. Static compositions provide structure for n’s hypnagogic digressions; there is a rigid formality to much of the filmmaking here, and from that flows a handful of languid sequences that flirt with otherworldliness. n obscures God’s presence in the world through meticulous, thoughtful filmmaking. This is perhaps the intent behind Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell’s combination of long takes and still frames: To force the audience to look at each image for minutes at a time like they’re poring over a Where’s Waldo? book, combing for proof of the Alpha and the Omega in Saigon’s neon lights and unfeeling concrete, or deep-green jungles teeming with life. The second half of the film follows Thiện on the road to find his estranged brother, and if a three-hour jaunt through Vietnam in search of faith and family sounds like an insurmountable challenge, Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell is anything but. It’s a journey jammed with pleasures we can all appreciate, and canopied by questions we all ask.–Andy Crump

39. A Traveler’s Needs

Director: Hong Sang-soo

Isabelle Huppert’s second collaboration with Hong Sang-soo is bursting with all of the hallmarks that audiences have come to expect from the Korean realist auteur: extended conversations occur over alcohol, local dishes are savored and a guitar is gently strummed in a domestic abode. The French icon plays Iris, a woman who has recently relocated to Korea and decides to offer one-on-one lessons in her native tongue to locals for a small fee. Her method is, admittedly, novel, opting to focus on the emotional weight of the language as opposed to the building blocks of grammar and syntax. Yet her presence has a profound effect on her pupils, who are perhaps more enamored by her innate charisma (and penchant for consuming milky-white makgeolli liquor) than her ability to impart tangible knowledge. —Natalia Keogan

38. Close Your Eyes

Director: Victor Erice

The first 15 minutes of Víctor Erice’s Close Your Eyes, his first feature in 30 years, are a time machine, instantly transporting you back to the filmmaker’s heyday. The distinct crackle and grain of the aesthetics, the soft white lighting and set decoration that resemble a canvas of Caravaggio, and the lengthy contemplative conversations all catapult the viewer—especially those like me who discovered Erice’s films in college—back to the time and space where we fell in love with his style and romanticism. His previous three films, The Spirit of the Beehive, El Sur and The Quince Tree Sun all begin with these nostalgic and emotive visuals. After three decades, Erice has barely missed a beat. He is back and he is the same. Or so it seems.

The rug pull after those first 15 minutes is something I immediately felt confused about, and even a bit disappointed over. My selfishness as a viewer, reflective of a greater cultural sense of wanting artists to keep doing exactly what we love them for—to keep giving us the same exact characteristic traits and qualities in their life’s work even as their life itself changes and charges along—took over. But Erice, like all great artists, is an antidote for his own appreciators’ myopia. Like many of the great ‘70s auteurs we have seen now growing old and facing the final confrontation with mortality—from Martin Scorsese to Francis Ford Coppola to Steven Spielberg—Víctor Erice sees the world having changed before his eyes. Unlike those other auteurs, he sees a world changing without him having said anything about it through the camera lens. Thus arrives Close Your Eyes, a 21st century masterpiece about remembering and forgetting the 20th century. —Soham Gadre

37. Chronicles of a Wandering Saint

Director: Tomás Gómez Bustillo

Writer/director Tomás Gómez Bustillo opens his feature debut, the spritely Chronicles of a Wandering Saint, with a low-key jab at piety: A woman kneels praying in a church pew, bathed in sunlight that peeks in through the windows. When the light shifts ever so slightly to her left, she scooches over, surreptitious as can be, to avoid notice from her fellow churchgoers and give the appearance that the light is following her rather than the other way around.

The woman is Rita (Mónica Villa), a woman of genuine devotion nonetheless compelled by a godliness complex. Rita is to worship as Daniel Plainview is to oil: She wants no one else to succeed. It’s a strange and self-contradicting quirk: Faking piety should theoretically bar one from entry into God’s kingdom. Rita, for her supposed meekness, is as vain as her faith is true; it’s a testament to the complications of spiritual belief that the two coexist within her without snapping her brain. Humans are, after all, imperfect, and committing to religious practice has a way of throwing our imperfections into sharp relief. If we adhere to dogma, we’re setting an expectation that we stick to its guidelines and rules.

Chronicles of a Wandering Saint maintains unflagging awareness of what it means to believe, and to worship and, maybe most of all, to hope. It’s one thing to have faith; it’s another to live a whole life without seeing your faith rewarded. Bustillo extends a great deal of sympathy to Rita, who aches to see a miracle in her lifetime – even if that means staging one, which clangs hard against at least two of the Ten Commandments. When Rita uncovers what she thinks is the long-ago-vanished statue of Rita of Cascia, she sneaks it back to her house, her long-suffering husband Norberto (Horacio Marassi) in tow; later, she asks Father Eduardo (Pablo Moseinco) for his take on whether or not it’s a sign. He tells her it’s a miracle. It isn’t, of course; it’s a terrible fabrication. But that won’t stop Rita from convincing her friends and neighbors otherwise. —Andy Crump

36. The Girl With the Needle

Director: Magnus von Horn

Such is the brutal pragmatism of director Magnus von Horn’s The Girl with the Needle, a gorgeously shot testament to the world’s callousness and cruelty, divorced from the petty construct of gender as it foists unimaginable suffering on the weakest among us. Difficult to classify, but hovering in the conceptual space between psychological horror and traumatic biography, the film is inspired by a real-life series of atrocities committed toward newborn babies in 1910s Denmark. Protagonist Karoline witnesses these horrors as both victim and accomplice, a woman whose dubious claim of ignorance resides in the moral gray area of what we can effectively choose to ignore by claiming to not understand. Sometimes, this is simply easier than uncovering the horrors of the truth we may suspect.

This kind of nihilism and cinematic misanthropy would perhaps unsurprisingly threaten to make the film oppressive to watch beyond even the degree to which this is absolutely intended, but that’s where the incredibly beautiful filmmaking of The Girl with the Needle raises it beyond the mere horrors of its depictions. Its visuals are absolutely stunning: Dramatic, high-contrast black and white cinematography captures a mythic, almost fairy tale sense of macabre wonder in the streets of the bleak, shadow-shrouded Copenhagen. In the back alleys, unpaved dirt paths hold pools of disgusting, stagnant water while dripping “apartment” rooms full of mold await residents who can cough up the difference between sleeping outside and with a marginal roof over their heads, a symbolic chasm between the lowest tiers of haves and have-nots. The active camera of cinematographer Michał Dymek cruises the streets like a pickpocket urchin, capable of evoking even a sense of sumptuous romanticism at times, as in the sequence where Karoline and her factory owner boss walk down opposite sides of the street as they flirtatiously gaze on each other. That brief sense of beauty is then expertly dashed with an immediate smash cut to the couple now rutting in a dirty alley while passerby stroll past in the background 30 feet away, ignoring the abjectly disgusting spectacle. Rarely does a piece of editing make you feel like you should immediately go shower away the secondhand filth of watching it. —Jim Vorel

35. Dune: Part Two

Director: Denis Villenueve

Set aside the complicated calculus of food, shelter and family needs. It’s time to shell out the big bucks and head to the local IMAX. To borrow from Nicole Kidman’s AMC commercial more explicitly, though you might not be “somehow reborn,” there will be “dazzling images,” sound you can feel and you will be taken somewhere you’ve “never been before” (at least, not since Dune). As befits a Part Two, Villeneuve’s film picks up in medias res, with Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet), his mother Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) and the Fremen encountering and dealing with a murderous Harkonnen hunting party while trying to reach the Fremen stronghold. From this encounter, Villaneuve nimbly guides the narrative from one key moment to the next, a veritable dragonfly ornithopter of plot advancement (with a few slower moments to allow the burgeoning relationship with Paul and Zendaya’s Chani to breathe). If the outcome of each narrative stop feels very much fated, that in turn feels appropriate given the messianic prophecy undergirding the entire tale. Dune: Part Two’s production design is as much center stage as its star-studded cast. Villaneuve pummels the viewer with the sheer scale and brutal, industrial efficiency of the Harkonnen operation—well, it would be efficient if not for those pesky Fremen—yet all of it is engulfed in turn by Arrakis itself. Meanwhile, the sound design and throbbing aural cues evoke the weight and oppressiveness of a centuries-spanning empire, the suffocating cunning of “90 generations” of Bene Gesserit schemes and the inescapable gravity Arrakis and its spice-producing leviathans exert on both. For those torn on whether it’s worth venturing forth to the multiplex, consider Dune: Part Two a compelling two-hour-and-forty-six-minute argument in the “for” column. And that “indescribable feeling” you get when “the lights begin to dim?” That’s cinematic escape velocity, instantly achieved. Next stop, Arrakis.–Michael Burgin

34. Flow

Director: Gints Zilbalodis

It sounds sort of like a Disney movie, only without enough plot – so maybe like an early Illumination bid for huggable franchising, computer-animated in the painterly textures of a recent DreamWorks feature: a cat, a dog, a lemur, a bird, and a capybara must work together to navigate a grand adventure. Only these animals don’t talk, much less yammer or crack wise, and, beyond a few minor conveniences, they behave more or less as animals might be expected to. The adventure, too, is a bit less magical and a bit more menacing than your average kiddie fare: There has been some kind of massive, possibly global flood, with little evidence of contemporary human civilization in sight, and some fanciful-looking whales that suggest an alternate world. Whatever the situation, never specified in part because the movie has no dialogue at all, this Latvian animated feature takes the audience through it with immediacy, empathy, and artistry. And for all its separation from the dynamics of contemporary American studio animation, this is a pretty great family film, and one that might well expand a child’s cinematic vocabulary to boot. It’s a testament to the power and flexibility of its chosen medium. – Jesse Hassenger

33. Bird

Director: Andrea Arnold

From the council estate-set Fish Tank to American Honey‘s scrappy road trip via grubby motels, Andrea Arnold’s movies are often gritty kitchen-sink dramas taking place against even grimier backdrops, from which she nevertheless unearths sublime beauty. At first glance, Arnold’s Bird seems to be set firmly within this tradition: It follows another marginalized young woman (Bailey, played by non-professional actor Nykiya Adams), who lives in a ramshackle squat with her father Bug (Barry Keoghan) and half-brother Hunter (Jason Buda). But Bird also marks a clear stylistic departure for Arnold. This film is both more raw and more fantastical than her previous works, existing on spectrum extremes in a way her other films haven’t.

But Bird isn’t really a human monster movie. It’s a fairy tale. Just as Arnold amps up the harshness, she also reaches beyond the limits of her traditional realism with a transcendent twist in the form of Franz Rogowski’s Bird. Sporting a skirt and an unplaceable accent, the childlike Bird arrives in Bailey’s life with a hazy backstory (he’s “looking for his family”). Bailey has a filmmaker’s reflex—the movie often splices in the wonderstruck videos she takes of local wildlife—and so she initially treats this strange figure with appropriate suspicion, pulling out her phone to film their first meeting for safety. But she soon softens once she identifies something pure and gentle in Bird’s eccentricity. Able to really see her in ways no one else does, Bird feels like a holy innocent in whom the worldly Bailey can nevertheless still recognize parts of her young self. —Farah Cheded

32. Sing Sing

Director: Greg Kwedar

30 miles north of New York City, situated directly on the bank of the Hudson River, lies Sing Sing, a maximum security prison that has been operational for nearly 200 years. For much of its lifespan, the institution has been known for its harsh conditions—it was the site of frequent electric chair executions until New York abolished the death penalty and is known for treating those imprisoned there with a severe sense of discipline and regulations. But by the late ‘90s, it had also become the founding location of the Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) program, which brings in theater creatives to work with the incarcerated population on developing and performing their own plays, offering a sense of community and camaraderie which has proven to have positive effects on the men. The program now exists at five other New York prisons.

Greg Kwedar’s sensitive, joyous Sing Sing does more than simply dramatize the workings of the RTA program, it incorporates participants into the very fabric of the film’s DNA. Most of the cast is composed of former New York prisoners who had gotten involved in RTA during their incarceration, turning the film’s depiction of a prison theater production into a reflection of honest, shared experiences by the performers. But, while much of Sing Sing’s success is owed to the moving nature of these men’s reality, they are not used as props. Sing Sing is an emotional prison drama that doesn’t beg for your tears amid all of the typical heartstring-tugging signifiers that come with the genre’s territory. It represents these lives sincerely and avoids grandiose histrionics, melding the real experiences of these men within the fantasy of filmmaking to find graceful emotional truths. —Trace Sauveur

31. Nosferatu

Director: Robert Eggers

What a strange yet hypnotizing task, the business of remaking Nosferatu, only slightly mitigated by the fact that it’s been done before. F.W. Murnau’s original 1922 silent film, subtitled A Symphony of Horror, adapted Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula without permission before the authorized 1931 edition (and is not especially less faithful to the novel than that early Universal Horror classic); then, in 1979, Werner Herzog remade the film as Nosferatu the Vampyre, a more verdant, eerily quiet version, expertly suffused with the grim unease that it could be taking place closer to our world.

That sense of creeping inevitability bleeds into the 2024 edition of Nosferatu, adapted by Robert Eggers – whose film that comes closest to a contemporary setting, The Lighthouse, takes place around the time Stoker’s novel was published. His Nosferatu echoes its official source, as the earlier film echoed its inspiration: In the nineteenth century, Thomas Hutter (Nicholas Hoult) travels to the remote castle of Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård), in the scenic Carpathian Mountains, to complete a real-estate transaction. Orlok becomes entranced by a photo of Thomas’s wife Ellen (Lily-Rose Depp), and when he makes his way to his new home, he brings vampiric pestilence with him as he stalks his adopted hometown, and Ellen in particular, with a kind of rigorously evil devotion. To call it love or even lust would not quite do justice to the totemic figure he cuts. This Orlok is neither the beastly, rodent-like version played by Max Shreck nor the elegant, be-caped Bela Lugosi. Get ready for a main vamp with a beard more prominent than any fangs, somewhere between a lumberjack and a living tree. This Orlok gives the impression of a vampire who audibly gulps down blood not exactly out of hunger, but to collect and taste what he lacks. —Jesse Hassenger

30. Green Border

Director: Agnieszka Holland

Green Border is at its most effective when its medium is the message. Stilling, frantic images shot through a bird’s-eye lens in black-and-white recall war films such as Schindler’s List, imbuing the contemporary conflict at the center of the film with a larger, historicist scope.

Perhaps more importantly, these images toe the line between an observational and experiential subjectivity, in which we are both inundated by a documentary-style realism as well as an acutely focused, first-hand experience of bodily movement—particularly within the contested border that threatens migrants’ ability to do so. We both understand the precarity of their very existence and embody their immediate, multisensory experiences of danger. In a world marred by the tragedy of displacement—casualties of myriad geopolitical, colonial and economic interests—Green Border’s resonance speaks for itself. Nevertheless, Holland’s choice of black-and-white cinematography is a striking one, an indication of a filmic and ideological continuity with her previous works Angry Harvest and Europa Europa, each of which relate Holocaust-set stories. In Green Border, her images of the present are coded with the pain of years past, if only to say—in compassionate, non-instructive fashion—that we ought not to repeat the machinations of death and destruction. We would do well to listen. —Hafsah Abbasi

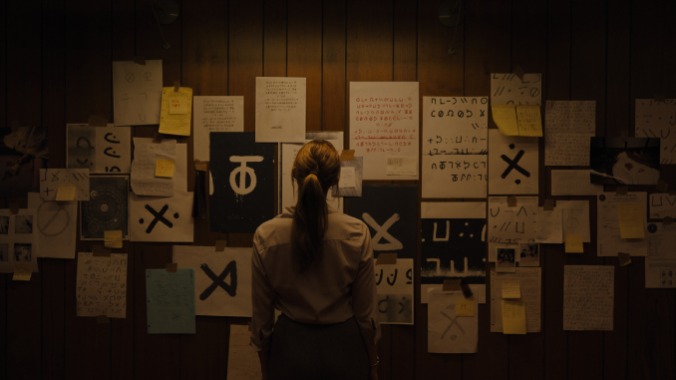

29. Longlegs

Director: Osgood Perkins

The first thing I wanted to do after seeing Longlegs is take a shower. Some horror movies have you looking over your shoulder on the way out of the theater, jumping at shadows in the parking lot. These are the horror movies that follow you. Longlegs doesn’t follow you. You’re drenched in Longlegs. It’s all over you—in your hair, on your clothes—by the time the credits roll. Its fear is less tangible than a slasher or a monster, even less than a demon. It’s just something in the air, in the back of your mind, like the buzz of a fluorescent lamp. Oz Perkins’ satanic serial killer hunt is his most accessible movie yet, putting the filmmaker’s lingering, atmospheric power towards a logline The Silence of the Lambs made conventional. Precisely crafted and just odd enough to disarm you, allowing its evil to fully seep in, Longlegs is a riveting tale of influence and immersion.

Longlegs’ dominos may somewhat inelegantly tumble through the (not hard to guess) twists and turns of its finale, but those pieces are of impeccable craftsmanship. A handful of impressively controlled performances, a dilapidated aesthetic rich with negative space, a queasy score, a methodical but always gripping pace, and one of the most original and upsetting horror villains in a long while. Perkins’ haunted vision is so convincing, you also might feel like scrubbing it off of you after you’ve hustled back to the safety of your home. —Jacob Oller

28. Meanwhile on Earth

Director: Jérémy Clapin

Great science fiction filmmaking so often boils down to elemental, poignant themes on the nature of ethical choices and how these moments can transform our lives: Crossroads moments, where the paths of possibility diverge in opposite directions. Choose one path, and perhaps you retain your humanity at the cost of your own destruction, be that physical, emotional, spiritual or symbolic eradication. Choose the other, and perhaps you sacrifice your soul for some other aim, altruistic or personal. Is the choice worth the cost? In the end, we each must decide for ourselves, as protagonist Elsa (Megan Northam) is made to do in the emotionally wracking and visually engrossing new French sci-fi drama Meanwhile on Earth.

Elsa’s family, and by extension her own personal development, are both encased in a casket of grief, slowly suffocating as they linger in stasis. Three years earlier, her brother Franck disappeared during an exploratory space mission, his ultimate fate unknown but safely assumed by all. His small town in the French countryside erected a statue to their fallen local hero in the center of a traffic roundabout, which Elsa feels compelled to occasionally deface not in opposition to her brother but as a way to retain some kind of symbolic ownership of his memory. Her family unit is frozen in place: Father entombed in his basement office, listening to crystalline piano concertos, mother and daughter working at the same senior memory care facility, where they provide succor to patients who have outlived all other forms of familial aid. For Elsa, the job was supposed to be temporary, something to help keep her busy and get her back on her feet following the disappearance of Franck, before she returned to her true passion for illustration and comic book art school. But without Franck’s motivating presence, his ceaseless support and energizing drive, Elsa is now stuck in place, lacking the inertia to truly restart her life. And that’s about when she first hears a voice from above.

Meanwhile on Earth is the mournful sophomore feature from director Jérémy Clapin, and like his beautiful, Oscar-nominated animated debut I Lost My Body from 2019, it delves into metaphysical themes of identity, self-worth and compartmentalization: How do we value others, and ourselves? What are the individual parts of us worth, and which parts make a whole? Can a person be complete on their own, without the ones they love? The film’s basic premise forces Elsa into confrontation with one of the most elemental moral dilemmas of all: What is the value of a human life? —Jim Vorel

27. Last Summer

Director: Catherine Breillat

French provocateur Catherine Breillat returns to the directors’ chair after a decade-long hiatus with Last Summer, a remake of the 2019 Danish drama Queen of Hearts. Yet Breillat and her co-writer, Pascal Bonitzer, make this story of shifting power dynamics and erotic taboos completely their own, elevating the thematic strengths of the sub-par original film. It follows Anne (Léa Drucker), a lawyer who specializes in adolescent sexual assault cases. Ironically, she becomes embroiled in a clandestine sexual relationship with Théo (incredible newcomer Samuel Kircher), her husband’s estranged son from his first marriage who has recently come to live with them. Their intense passion constantly threatens to expose their clandestine affair, causing mounting anxiety and, eventually, major consequences for the couple and their loved ones. If the illicit presence weren’t enough to draw you in, the promise of a recurring Sonic Youth needle drop should hopefully do the trick. —Natalia Keogan

26. Love Lies Bleeding

Director: Rose Glass

Love Lies Bleeding is, in actuality, a far more effective horror film than Saint Maud. Filmmaker Rose Glass excels at crafting horrific images, moments of pure grotesquery and terror, and she pushes the boundaries of an otherwise grounded thriller-crime drama into something that resembles a gorgeous night terror. Sensuality oozes from every frame for a film that isn’t even terribly gratuitous during its sex scenes. But the physical act of sex between bodybuilder Jackie (Katy O’Brian) and gym manager Lou (Kristen Stewart) equals otherwise non-sexual scenes, such as Lou jabbing a syringe into Jackie’s butt cheek, or Lou Sr. (Ed Harris) whispering in Jackie’s ear before she fires a gun—or even Jackie’s roid rage-fueled murder of JJ (Dave Franco), which plunges Jackie and Lou’s passionate neophyte romance into an explicitly gay Thelma and Louise, where the two lovers must flee the wrath of Lou’s criminal family. The connection between the two women is desperate, carnal and overwhelming, if simultaneously toxic and even a little superficial. Suddenly, nothing matters to Lou quite as much as her ripped new girlfriend, whom she’s more than happy to continue supplying with body-enhancing drugs that cause Monstar-like eruptions under her skin in sequences of heightened surrealism. As the walls close in on Jackie and Lou, Glass amps up the tension with tight, suffocating shots, propulsive editing and an absorbing score by Clint Mansell. At the center of it all is Jackie and Lou’s cacophonous romance. By all accounts, the gay Romeo and Juliet were doomed from the start. Stewart and O’Brian have incredible chemistry, and Stewart’s understated naturalism really shines. Love Lies Bleeding is easily one of the best of 2024 so far: A thorny, thrilling narrative about two fucked-up women that is—most importantly—genuinely, scintillatingly hot. The film is also very obviously about the myriad, terrifying ways human beings express love to one another, and on the surface seems to question which ones are more or less valid.–Brianna Zigler

25. The Piano Lesson

Director: Malcolm Washington

Adapting a stage play to cinema can be tricky business. Often the intimacy and defined parameters of a theater setting become a problematic albatross for screenwriters and directors trying to stay faithful to the spirit of the work. In the wake of Pulitzer Prize-winner August Wilson’s death in 2005, Denzel Washington has made it a personal priority to shepherd the playwright’s works to film for wider audiences. He starred in and produced Fences in 2016, and then produced 2020’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom and the latest, The Piano Lesson. And each adaptation has gotten progressively stronger, culminating here in director Malcolm Washington’s feature directorial debut, where his fresh eyes on the play, confidence with his actors and overall inventive approach to the themes and subtext of the play result in the best film of the trilogy.

Wilson’s play centers on the generational legacy of the Charles family, most recently of Sunflower, Mississippi. Just two generations separated from slavery, and still victims of the violence of the segregated South, siblings Boy Willie Charles (John David Washington) and Berniece Charles (Danielle Deadwyler) are living their adult lives separately. In Sunflower, Boy Willie’s got an opportunity to buy 150 acres of land from the family who enslaved his grandparents and great-grandparents if he can come up with the last bit of money to make the sale. Widow Berniece, meanwhile, lives in a nice house in Pittsburgh with their uncle Doakes (Samuel L. Jackson) as she raises young Maretha (Skylar Aleece Smith) in a relatively more progressive part of the country. As far as they’ve come, the family is still haunted by their recent past. Their ancestor’s trauma is literally personified in the intricately carved Charles family piano, which stands proudly in the front room of Berniece’s home.

For Berniece, the piano is a vessel for ghosts both literal and metaphorical. She and her mother have a sorrowful relationship with the instrument that requires Bernice, and in turn her daughter, to have distance from it. For Boy Willie, it’s his conduit to financial independence. If he can sell it, then he can buy the very land his late sharecropper father told him would be his path to freedom. And thus the conflict is laid out via an object that has its own particular history that will be revealed as the story unfolds. —Tara Bennett

24. Rebel Ridge

Director: Jeremy Saulnier

Writer/director Jeremy Saulnier’s films are never shy about abrupt savagery born from endlessly escalating suspense. Both Blue Ruin and Green Room assemble whole cosmologies of tension around the series of decisions that must be made by people totally unprepared for the graphic afterbirth of very simple violence. In Green Room, Pat (Anton Chekhov) and his poor touring punk band are so callously unready for the slaughter to greet them at a white supremacist bar in rural Oregon (go figure) that they cover Dead Kennedys’ “Nazi Punks Fuck Off” for a room full of skinheads. The nightmare that follows isn’t the direct result of their song choice, but punks aren’t known for self-preservation either.

Rebel Ridge is Saulnier’s second film for Netflix after 2018’s dreamy, dreary Hold the Dark. An open riff on First Blood, with shades of the 1973 Joe Don Baker vehicle Walking Tall, Rebel Ridge also feels like a determined return to the relentlessness of Saulnier’s first films. But as Terry’s plans unravel and contingencies disappear, Saulnier doesn’t double down on the grisly nature of Terry’s fate. Instead, with Pierre’s disarmingly symmetrical face carrying the majority of Rebel Ridge’s frames, the writer-director’s never been more restrained. Without breaking into gnarly gore like in Green Room, nor surprising with a burst skull or two like in Blue Ruin, the film barrels forward heedlessly, every conversation, interaction and inevitable smoke-swathed shoot-out about the way power is wielded and manipulated between characters. Even steeped in political commentary, Rebel Ridge is breathlessly staged. —Dom Sinacola

23. The Beast

Director: Bertrand Bonello

Bertand Bonello is more than adept at traversing genre: he’s made a superb period piece, contemporary thriller, biopic and experimental satire, but with The Beast, he manages to roll all of these explorations into a scintillating epic that spans decades, continents and language. Léa Seydoux plays Gabrielle, a woman living in Paris circa 2044. AI has become humanity’s overlord, and in order to qualify for the limited human-manned positions available, Gabrielle must undergo a DNA purification process to purge all of her memories and emotions—including those that linger from past lives. Through this process, she is transported back to two of her previous realities: as an acclaimed pianist during France’s La Belle Époque and as an aspiring model and actress in 2014 Los Angeles. In all of these eras, she encounters a striking young man (George MacKay), igniting a fire within her that threatens to be snuffed out by technological dystopia. Pop culture jumpscares include Dasha Nekrasova, Elliot Roger and Trash Humpers; the fact that it all works is a testament to Bonello’s singular vision and scope. —Natalia Keogan

22. The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed

Director: Joanna Arnow

The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed begins with writer/director Joanna Arnow’s naked body curled up next to her character Ann’s dozing dom, Allen (Scott Cohen). She humps him slowly and awkwardly over the duvet, and quietly encourages his lack of interest in her own sexual gratification. It’s true that their sub-dom dynamic is largely focused on Allen’s pleasure, while Ann is merely his willing servant. It’s a dynamic that they’ve shared together since Ann was in her mid-twenties, with Allen at least 20 years her senior. But later in the film, Ann reveals that she can’t actually achieve climax from physical touch, anyway. Throughout the film, Ann hops between a small handful of BDSM relationships—the only kinds of relationships she’s ever been a part of—until she meets the soft-natured Chris (Babak Tafti). It’s here that Ann decides she’s done with the sub-dom life and is finally willing to try “real” dating. For as chaotic as this arc sounds, The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed is an incredibly still film. There is hardly any non-diegetic music, and characters do not say very much. These ordinary scenarios are completely hypnotic to watch and to hear. Despite Ann being something of a wallflower, her low voice and deadpan delivery are utterly alive, and there is also life in New York, even when the city is not jumping from the screen like it usually does in movies. The molasses feel of the film is such a welcome contrast to the normal stereotype of New York City as fast-paced, on-the-go and constantly interesting. Arnow also makes these boring parts of life seem so daunting. The job that won’t get better, the sex that won’t get better, the family that won’t get better; the love that might get better but could still fall apart at any moment. The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Past beautifully observes how the ridiculous mundanities of being alive are some of the most difficult.–Brianna Zigler

21. Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point

Director: Tyler Thomas Taormina

Tyler Thomas Taormina’s new holiday classic captures the busy, noisy, affectionate, occasionally fractious gathering of a large extended family somewhere on Long Island with an almost unnerving verisimilitude in depicting the chaotic yet familiar rhythms of such get-togethers. Yet Taormina’s film isn’t exactly a documentary-style, fly-on-the-wall experience, either. Existing somewhere outside of time – cell phones are present, but not smart; TVs are boxy but not ancient; the youth are recognizable but not specifically brain-poisoned in that ultra-online way – like the best (and strangest) holiday breaks, Christmas Eve at Miller’s Point grows more idiosyncratic and evocatively diffuse as it goes on, following some teenagers as they peel off from their family and sneak into a desolate, snowy, ritualized world of their own. Finally, a Christmas movie that’s reminiscent of David Robert Mitchell’s The Myth of the American Sleepover and the more bittersweet moments of American Graffiti, the perfect rebuke to the streaming holiday content mill. – Jesse Hassenger

20. A Different Man

Director: Aaron Schimberg

You can change your hair, you can change your clothes, you can surgically change your face to that of Hollywood hunk Sebastian Stan, and you’ll still be the same awkward, unlikeable weirdo on the inside. Or at least, that’s what writer/director Aaron Schimberg asserts in A Different Man, an exhilarating blend of body horror, dark comedy, sci-fi and romance. Even with all the power of the 21st century’s most scientifically advanced beautifying technology, the human race has still not figured out a medical surgery to make us better people, perhaps because this wouldn’t be a particularly profitable industry (but that’s a discussion for another time).

It’s not that Edward (Sebastian Stan), an unsuccessful actor afflicted with neurofibromatosis, is a particularly vain individual. In fact, he’s hesitant to undergo the radical facial surgery that eradicates his disfigurement. It just so happens that the surgery gives Edward Patrick Bateman levels of handsomeness. Can you blame Edward for taking that chance? Who among us wouldn’t opt to look a hundred times more conventionally attractive?

It’s once Edward abandons his own name for a fake sounding one and forsakes his former nice guy identity for a new debaucherous life as a wealthy real estate asshole that we realize, hey, maybe this wasn’t such a great guy to begin with. On top of that, maybe I, the viewer, am also an asshole for assuming Edward was a decent guy just because his face was deformed. This is a layer that Schimberg explored with his previous film Chained for Life; is it more morally deplorable to gawk at or to pity the severely deformed? —Katarina Docalovich

19. Dahomey

Director: Mati Diop

The silent witnesses to colonial conquest are given a voice for the first time in Mati Diop’s intelligent hybrid documentary, which follows her 2019 debut Atlantics. It unfolds amidst France’s decision to return 26 artworks (out of a total 7,000) pilfered from the African kingdom of Dahomey during its imperial rule. Diop follows these artifacts through the process of packing them up in Paris, receiving them in modern-day Benin and putting them back on display for citizens in the old royal city of Abomey. Three of these sculptures are given deep, booming voice over, wherein they muse about the act of repatriation, enduring scars of colonialism and their relationship to this familiar yet irrevocably changed land. Echoing and sometimes challenging these sentiments are students from the University of Abomey-Calavi, who Diop captures in an extended scene that illustrates how violent histories feed future activist fervor. —Natalia Keogan

18. Exhuma

Director: Jang Jae-hyun

Writer/director Jang Jae-hyun’s Exhuma bobs and weaves in ways American exorcism stories couldn’t fathom. Shades of The Wailing’s transformative storytelling covers its haunted burial grounds, traditional exhumation practices and resentful spirits, all with filmmaking ambitions that think outside the (coffin) box. Exhuma presents as ordinary until it’s not, a splendid feature of slippery South Korean thrillers. Jang’s gravedigging ghost hunt takes multiple forms, each one more ferocious than the last, as nationalist histories manifest as a seething threat to modern generations.

Exhuma follows a quartet of afterlife specialists: There’s renowned shaman Hwa-rim (Kim Go-eun), her full-body inked partner Bong-gil (Lee Do-hyun), “Geomancer” AKA feng shui master Kim Sang-deok (Choi Min-sik) and mortician Yeong-geun (Yoo Hae-jin). A wealthy Korean American family hires Hwa-rim and Bong-gil to eliminate a “Grave’s Call” curse afflicting their newborn son; Sang-deok and Yeong-geun are enlisted to help locate the problem ancestor’s grave. Together, near North Korea’s border, the party discovers a nameless tombstone. They’re in the right place, but Sang-deok can’t shake an alarming aura around the site. Some jobs aren’t worth the payday, as Sang-deok and his fellow undead bloodhounds are about to find out.

Jang’s approach welcomes international audiences into South Korean lore, where spirituality thrives without scoffs or sarcasm—it’s an immersive treat because there’s no disbelief or doubt to bog down the storytelling. Hwa-rim doesn’t waste time clashing against that one annoying pest who continually downplays supernatural experiences (the “they’re not real” plant). A propulsive energy trims fatty tropes off Exhuma’s lean cut of vengeful, hereditary malevolence. —Matt Donato

17. Janet Planet

Director: Annie Baker

Janet Planet immerses the audience in the boonies of Western Massachusetts during the summer and early autumn of 1991, allowing the viewer to absorb countless details of the period, mood, and relationships. Lacy (Zoe Ziegler), who will enter middle school in a few weeks, lives with her mother Janet and doesn’t have real friends of her own, which places her uncomfortably close to the adult orbit of failed romances and rootless non-careers. Her mom has slightly flaky, woo-woo vibes, but she’s found some footing as an acupuncturist; her old friend Regina (Sophie Okonedo) quietly grouses – to Lacy and therefore pretty inappropriately – that a $30,000 inheritance allowed Janet the luxury of going back to school. Regina is fleeing a relationship with Avi, and becomes a rent-free tenant at Janet’s home. She’s preceded by Janet’s sort-of live-in boyfriend Wayne (Will Patton), who seems like a gentle man – so recessive that Baker barely shows his face head-on – until he doesn’t. Through this and other little episodes, Lacy lurks in her own house, the watchful main character in Janet’s story.

Mother and daughter both have what Janet later refers to as “forthrightness” while seeming, to some extent, at a loss for how to make each other happier. In the first scene of the film, Lacy calls home, asking her mother to pick her up early from summer camp in the most dramatic terms possible (albeit spoken in Lacy’s usual unnervingly even-handed tone). When Janet dutifully retrieves her, and Lacy realizes that (a.) at least one of her campmates considers her a friend and (b.) Wayne will be staying with them, the girl reconsiders – too late, of course. That emotional limbo sets the movie on edge immediately, and vividly; it’s a masterful establishment by Baker that paints a portrait of Lacy’s relationships while allowing room for more details to emerge.

Shooting on 16mm celluloid, she captures moments that will become comforting memories, whether they should be or not: Lacy’s race through a local mall with a sadly temporary friend becomes a bucolic romp. The theme music of Clarissa Explains It All watched on a sick day becomes hypnotic. The many great scenes in Janet Planet underscore the frustrations of its few bad ones: Even an emotionally tumultuous childhood can be a lot more absorbing than the indulgences of the adult world. —Jesse Hassenger

16. Red Rooms

Director: Pascal Plante

Red Rooms is a movie fixated on a single performance, itself fixated on a serial killer. The performance is that of Juliette Gariépy, fantastic as the unblinking Kelly-Anne. The serial killer is the Gollum-like and dead-eyed Ludovic Chevalier (Maxwell McCabe-Lokos), accused of butchering three young girls live on a pay-per-view stream. This dark web snuff stream is a Red Room, and it’s unclear what aspect of the case Kelly-Anne is obsessed with as she stares intently in the background of the film’s gripping courtroom scenes.

Is she another romanticizing rubbernecker here to ogle real deaths as true-crime entertainment? Or is it darker? Is she—like her trial-observing counterpart Clémentine (Laurie Babin, excelling at a more emotive, girlish foil)—a hybristophilic fangirl, a prison groupie who’d send a love letter to Ted Bundy? These questions, and the complexity that lies underneath, drive Red Rooms beyond the effectively daunting way writer/director Pascal Plante reveals the details of the central crimes. And, without ever showing too much, Plante has crafted one hell of a stomachache. He doesn’t show, and he barely tells. The little we do glean only adds to the dreadful realism. Less than two hours, yet feeling like an eternity thanks to some well-planned and executed long takes (featuring some particularly engaging monologues from Natalie Tannous, playing the prosecutor), Red Rooms traps us in the mindset of its intense lead as we get ever more involved with the case. —Jacob Oller

15. No Other Land

Directors: Basel Adra, Hamdan Ballal, Yuval Abraham, Rachel Szor

Simply put, there is no film more vital this year than No Other Land, a documentary collectively helmed by Basel Adra, Hamdan Ballal, Yuval Abraham and Rachel Szor that captures the violent ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from the Masafer Yatta region well before the events of October 7, 2023. Though this film marks all of their directorial debuts, it centers on the connection and collaboration between the West Bank-born Basel and Israeli Yuval, who live very different lives as activists and journalists due to the occupation. Through decades of footage that Basel and his family have shot over the years, the long-standing Zionist project of displacing Palestinians and suppressing their basic human rights is on full display; contemporary footage, largely shot by co-director Rachel Szor, charts how zealously the IDF has escalated its destruction of Palestinian lives since 2019. The film ends on a literal shot that will rally anyone with a conscience into unwavering support for a people who have since only faced overtly genocidal inhumanity. —Natalia Keogan

14. Daughters

Directors: Natalie Rae, Angela Patton

For ten long weeks, men who are incarcerated in a Washington, D.C. prison eagerly anticipate a rare opportunity to reunite with their daughters in the profoundly moving documentary feature Daughters. The film from co-directors Natalie Rae and Angela Patton follows these fathers and their children as they prepare for a “Date with Dad” dance that will allow them to be reunited for six hours, a rare opportunity for physical connection as prisons across the board begin to limit in-person visitations. As part of the two-and-a-half-month lead-up to the dance, those eligible to participate complete a fatherhood coaching program, entailing an informal roundtable where the men are able to express their complicated feelings about their own upbringings and anxieties over their mandated absence. Rawly exposing the cruelty imposed upon predominantly Black children by the carceral state while also capturing the emotional whiplash of this fleeting encounter, Rae and Patton construct a visually stunning and narratively resonant portrait of love and longing.

Undoubtedly aided by Patton’s involvement, the film’s candid confessions speak to a level of involvement from the directors that never borders on invasive or insensitive. There is no discussion of the fathers’ charges, only of the length of their sentences, as that’s the element of their incarceration that most profoundly impacts their relationship with their daughters. The girls are also allowed to express their unvarnished thoughts, reflecting the genuine comfort they must have felt with the filmmakers. Yet even amid these sincerely heart-wrenching scenes, the actual camerawork, lighting and framing are artistically inclined, making Daughters all the more riveting to engage with; the resulting dance itself is awash in a beautiful haze, as if the prickly pang of nostalgia colors each ruefully impermanent moment. —Natalia Keogan

13. Apolonia, Apolonia

Director: Lea Glob

We meet Apolonia Sokol as she prepares for her 26th birthday party. A shaving cream beard coats her face as she trims her bangs in the mirror, hair trickling into the sink below. The first voice we hear, however, is not of Apolonia, Apolonia‘s subject, but director Lea Glob, who narrates the moment she captures behind her camera.

The Danish filmmaker met Sokol, a contemporary French painter, in 2009 when she set out to portray her on camera for a film school project — the result being 13 years of candid footage, spanning Sokol’s unconventional bohemian upbringing in her parents’ theater to her later accomplishments as a professional figure painter. Striking and tender, the film divulges Sokol’s evolution in both her own identity and art — two things she sees as interconnected.

At the beginning of Apolonia, Apolonia, Glob proclaims her goal: To create an eternal portrait of her subject, one that evokes the paintings of kings. She accomplishes this feat, leaving a dazzling record of Sokol’s life that champions and carries on her legacy as an artist. It feels as if in the 13 years of shooting, Glob rarely turned off her camera, utterly captivated by her subject, and the result leaves us just as transfixed. Though she rarely appears on screen, Glob’s presence in the film shows how the women on either side of the camera inspire each other in tandem. As both women face tragedies toward the end of the documentary, their support for one another punctuates their bond and parallel experiences of womanhood. —Sage Dunlap

12. The Substance

Director: Coralie Fargeat

In terms of sheer dominance over The Discourse, there can be no doubt that 2024 belonged body, mind and soul to Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance. A quantum leap forward in terms of ambition and sophistication after her slick but streamlined 2017 debut thriller Revenge, The Substance is an ode to self-destruction and bruised egos, greed and blindness to cycles of perpetuated avarice.

Much of the film’s success comes down to the incredible willingness that Fargeat taps into in its performers to make themselves as reprehensible–and yes, “ugly”–as possible, becoming portraits of desperate individuals who have long since abandoned common decency or a shred of empathy. That of course includes Demi Moore’s Elisabeth, who pathetically clings to the faintest shreds of vicarious achievement despite the fact that she can’t really enjoy them, addicted to the rush of seeing her avatar succeed even as she resents herself and physically drains herself dry. It includes Dennis Quaid’s not-so-subtly named Harvey, a slavering psychopath who treats his talent with no more respect or tact than he puts into masticating an entire plate of shrimp in a sequence that rivals any of the other stomach-churning sights of The Substance. And the willingness to tap into the depraved side of human nature even applies to Margaret Qualley’s pristine Sue as well, a woman so eager to debase and objectify herself just to live up to the archaic standards of success set by Elisabeth, never once considering that her unique circumstances could afford her a second chance to live life different than Elisabeth previously did “in her prime.” The tragedy of The Substance is that Sue can’t even conceive of a more fulfilling alternative than willingly throwing herself into the exact same meat grinder that chewed up Elisabeth and spit her out, except Sue is apparently determined to speedrun the entire process.

On a thematic and visual level, The Substance has perhaps been given more credit at times for its outrageousness or uniqueness than it necessarily demands, which mostly serves to illustrate how this kind of boundary stepping body horror has become a rarity to see on a big screen in recent years. Reactions to the film almost serve as a litmus test for whether any prospective horror geek has ever gotten around to seeing Brian Yuzna’s Society from 1989–if you have, then you probably find Fargeat’s film a bit less shocking. But the sheer, unapologetic gusto with which The Substance tackles its squelchy, bone-cracking delights makes its combo of visceral transformation and misanthropic satire into a vital piece of modern horror filmmaking, anchored by some of the best performances the genre has seen in recent memory. —Jim Vorel

11. Terrestrial Verses

Directors: Ali Asgari and Alireza Khatami

Ali Asgari and Alireza Khatami open Terrestrial Verses with Tehran’s skyline gradually brightening beneath a welcoming sunrise. The image is deceptive. Rather than a descent into darkness signaling imminent peril, Asgari and Khatami propose that we should be wary of the light instead. In Tehran, atrocities are committed in plain sight, smack dab in the middle of day, concealed only by office doors, assuming the folks committing bother concealing them at all. As if driving the point home, the film punctuates morning’s advent with cacophony comprising birds’ ominous caws, the din of alarms blaring and a chorus of voices joined in layered angst. This is not a happy city.

Its citizens aren’t happy, either, or maybe they are outside the circumstances Asgari and Khatami catch them in. Terrestrial Verses documents a cascade of transgressions, both micro and macro, made against its cast of nine principal characters: A new dad (Bahram Ark), students preteen (Arghavan Shabani) and teenage (Sarvin Zabetian), a rideshare driver (Sadaf Asgari), people seeking employment (Faezeh Rad and Majid Salehi), a man applying for a drivers license (Hossein Soleimani), a filmmaker (Farzin Mohades) and a dear elderly lady (Gohar Kheirandish) are each subjected to varied humiliations by Iran’s bureaucracy, for crimes those of us in the West can’t conceive of as criminal. Imagine being told the name you’ve chosen for your newborn son isn’t Muslim enough. Choose another one. “David” is forbidden.

The degrees Terrestrial Verses’ antagonists go to for the sake of exerting petty authority over its hapless leads read as alternately comical and cruel. But for all of its cosmic implications, the film remains steadfast in its human devotions. —Andy Crump

10. Inshallah a Boy

Director: Amjad Al Rasheed

Inshallah a Boy has a quiet ordinariness to it. In just under two hours, the film tells the story of Nawal (Mouna Hawa), a personal support worker in her 30s, whose life is upended by the sudden death of her husband. At first, she has to deal with the grief of losing a spouse and taking care of her young daughter. But then her brother-in-law Rifqi (Haitham Omari) starts demanding payments for the money he is owed. According to local custom, he can lay a claim to Nawal’s home and take guardianship of her daughter. Nawal’s only recourse is a male heir. In order to keep her brother-in-law at bay, she claims to be pregnant. Over a course of three weeks, Nawal faces one challenge after another as she fights to own what’s rightfully hers and to protect her daughter. From the opening frame, Jordanian filmmaker Amjad Al Rasheed, who also wrote the film with Rula Nasser and Delphine Agut, draws us into the absurdities of Nawal’s life. Inshallah a Boy opens with her trying to retrieve an errant bra that’s somehow ended up hanging on an electrical wire outside her closed-off balcony. She tries reaching it with a broomstick handle, quiet frustration etched out on her face. Any woman who has grown up in a crowded city in the global south, where public spaces seldom feel accommodating or safe for women, will relate to Nawal’s peculiar predicament. Underwear is never meant to be seen, even as a mere garment—forget the concept of airing dirty laundry. Throughout Inshallah a Boy, we get a sense of Nawal’s fortitude, which hits several breaking points as circumstances keep testing her faith—in her religion, her family, her marriage and ultimately herself. Palestinian actress Hawa shines as Nawal, and is ably assisted by a supporting cast in her portrayal of a widow sometimes barely grasping at straws. There’s a lived-in weariness that Hawa taps into; her version of Nawal is never distraught, nor enraged—although she has flashes of outbursts. She simply does not have the luxury. The way that Hawa is able to articulate Nawal’s moment of personal crisis, in the furtive look she gives her sister-in-law or the exasperation she reserves for her own brother, makes for a commendable performance. Inshallah a Boy doesn’t give any clear answers. Instead, the film offers a look at the life of an ordinary woman in Jordan, going through an ordeal likely faced by many like her. In an interview, Al Rashad spoke of being inspired by a real-life incident within his own family. A relative was in a similar situation as Nawal, and he wondered, “What if she says no? What if she decides to fight and what are her options?” It’s remarkable how that inquiry led Al Rashad to write and direct such a compelling drama about the limits and liberations of faith.–Aparita Bhandari

9. Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

Director: George Miller

If you ever took a class on the Greek classics, you might remember that the epics of Homer are defined by their first words. The Odyssey is the story of a “man,” while the Iliad is a story of “μῆνις,” which is often translated as wrath, rage…or fury. The epics of George Miller barely need words at all, yet Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga is the Iliad to Fury Road’s stripped-down Odyssey. The latter’s elegant straight-line structure is replaced with lush chapters, documenting the interconnected systems of post-apocalyptic nation-gangs through the years. Through it all, a Dickensian hero clings to this world’s seedy undercarriage. Reducing Furiosa down to a single word does it as little justice as it does the sagas it scraps, welds and reuses like its countless Frankenstein vehicles. But understanding George Miller’s Fury Road prequel as the story of war—of sprawling futility, driven by the same cyclical cruelty that turned its deserts into Wastelands—makes it far more than a satisfying origin story. (Though, it’s that too). Furiosa speaks the language of epics fluently, raging against timeless human failure while carrying a seed of hope. What we learn, we learn through the eyes of Furiosa, from the moment she’s ripped from the Green Place of Many Mothers as a child, to the second before she tears out of Immortan Joe’s Citadel, smuggling Fury Road’s stowaways. As Furiosa grows from traumatized child (Alyla Browne) to damaged adult (Anya Taylor-Joy), she survives the slave-labor bowels of the Citadel, claws her way into a position aboard a trade caravan and waits for the perfect moment to enact revenge upon her initial captor, the chaotic, power-hungry biker warlord Dementus (Chris Hemsworth). Pushing back on the various men who hunt them, Browne and Taylor-Joy’s performances work in stunning tandem, steadily heating the steely young girl’s resolve until it turns molten. When you match the most powerful eyes in the business with Miller’s evocative framing (Furiosa is shot a bit like Galadriel’s brush with evil in Lord of the Rings—somewhere between avenging angel and Frank Miller cover), you get all the character you need. Each action scene, whether another amazing chase or a desperate rescue mission deep in enemy territory, is driven just as deeply by visual logic as by spectacle. These stunning visions of neo-medieval torture in Hell’s junkyard only work if we can make sense of it all. Furiosa is a film well-planned and deeply dreamed. Miller’s movies strip folkloric epics down to their basic mechanical parts, functional skeletons that run on raw emotion like the war machines running on piss and guzzolene.–Jacob Oller

8. Nickel Boys

Director: RaMell Ross

The experimental style of Nickel Boys recalls the more adventurous side of NYFF, where international directors will often bring formally rigorous, ambitious, or challenging films to an appreciative audience: For the most part, director and cowriter RaMell Ross constructs his film version of Colson Whitehead’s acclaimed novel entirely in point-of-view shots.

First, we’re only privy to the first-person experiences of Elwood (Ethan Cole Sharp, then Ethan Herisse), a Black high school student in the Jim Crow-era Florida of the early ’60s. We see what Elwood sees, which means not much of his actual face or body, catching a glimpse of him as a faded image in a store window, where he gazes at a row of television sets – or, in one beautiful shot, his reflection in the metallic trim of an iron held by his grandmother Hattie (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor). Early in the film, Elwood, a strong student who qualifies to take classes at a local college, is wrongly accused of helping to steal a car. (He’s only just accepted a ride from a stranger.) The police send him to Nickel Academy, a reform school that Whitehead based on a real institution, trafficking in segregation and cruelty. Once there, Elwood, who earnestly believes he can work his way out of the system, befriends the more cynical Turner (Brandon Wilson), opening up a second avenue for POV shots. From there, the movie alternates between the two of them. Though they grow close, the two boys rarely get to share the frame – which makes one wonderful overhead-mirror shot, reproduced on the film’s poster, even more memorable.