Feels Good Man Is the Rarest Pepe of All: A Good Meme Documentary

Photos Courtesy of PBS

One of the more evil things people do on the internet is couch their cruelty in silliness, immaturity, and irony. An effect of this is to dissuade people from talking seriously about memes, “normies,” trolls, blackpill, incels, and other topics with similarly humiliating names to say out loud. It’s embarrassing. It’s also indicative of this particular vein of hate’s childish roots and hard-to-combat nature that the diction around toxic online behavior is so goofy. Nobody wants to get angry at Nazis when they’re hiding behind a cartoon frog, because then the Nazis get interviewed by the network news and laugh it off. Thankfully Feels Good Man is smart enough to understand that and empathetic enough to be the story of the frog rather than the story of the Nazis.

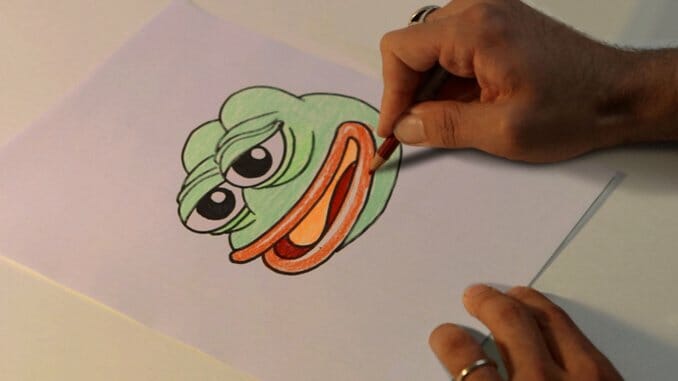

Director Arthur Jones’ documentary, airing as the premiere of a new season of PBS’ Independent Lens, is a crash course in weird internet, alt-right politics, IP, the feedback loop of social media, and the easygoing Kermit that ties them all together: Pepe the Frog. Much more than an extended deep dive into its Know Your Meme entry, Feels Good Man approaches the star of artist Matt Furie’s Boy’s Club comic, whose face and expressions were co-opted and corrupted by particularly sinister online communities, with warmth and intelligence.

The film starts fast, looking like it’ll be a thrumming chronological telling of Pepe’s inception, his adoption by toxic message boards like the chans and bodybuilding forums, his mainstream crossover, and the retaliatory intensification of his debauchery. Thankfully, after some necessary stage-setting, Feels Good Man allows itself space to breathe. That separation, at least for a few moments, from the inevitable political narrative allows the production to reclaim the character just as Furie seeks to.

While there’s a bit of meme explanation (even Furie doesn’t know if he’s saying the word right) for newcomers, those deep into the dark recesses of being Extremely Online won’t feel put off by this extended hand to the (perhaps more mentally sound) rest of the world. Pepe’s simple encapsulations of intense modern and postmodern feelings—everything from red-faced rage to ennui to simple stoner pleasure—belong on a monitor. His face is all big wet eyes and lips, perfect (in both practical and psychological terms) for the expressions of a cartoon toy (as was Furie’s inspiration) or an emoji. Those of us that communicate with vocabularies that are half words, half reaction GIFs are always on the lookout for those quick-and-easy visual shortcuts.

Pepe is immediately identifiable as a creation of Furie, whose personal aesthetic (a little like early Mac DeMarco’s endearing, neon-colorful dirtbag manchild) bleeds into his art. He’s a modern hippy whose soft words and “peace, love, and good vibes” energy are the quintessential doomed qualities of an exploited artist. “That’s a happy little frog,” Furie says after drawing us our first Pepe. The doc demonstrates the frog’s delightful slacker appeal as a pizza-slurping, mattress-on-the-floor kinda guy that wouldn’t feel out of place sleeping on the sofa of Tuca & Bertie. It’s a literal rebranding campaign, in that it’s trying to go back to its original brand. Rambunctious psychedelia permeates the film through its lovely, striking animated segments (another savvy formal move to define the character through his origins) and it’s the purest you get to see Pepe. The rest comes from the memes.

After Furie uploaded a particular page of Boy’s Club to MySpace back in … well, MySpace times, Pepe’s mug was nabbed, altered, and used in every context you can think of. Some are harmless: Pepe is sad, Pepe is happy. Most are not. Pepe became such a frequent signifier of anti-Semetism, racism, and violent rhetoric—particularly as he became associated with Donald Trump’s rise to power—that he got added to the Anti-Defamation League’s list of hate symbols. The many examples make you feel sorry for the person having to go through the boards. Their bounty is a boon of DIY artwork, mined from anonymous internet archives, demonstrating an evolution that mirrors that of online spaces themselves: harmless surfaces giving way to rotted and manipulable interiors.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-